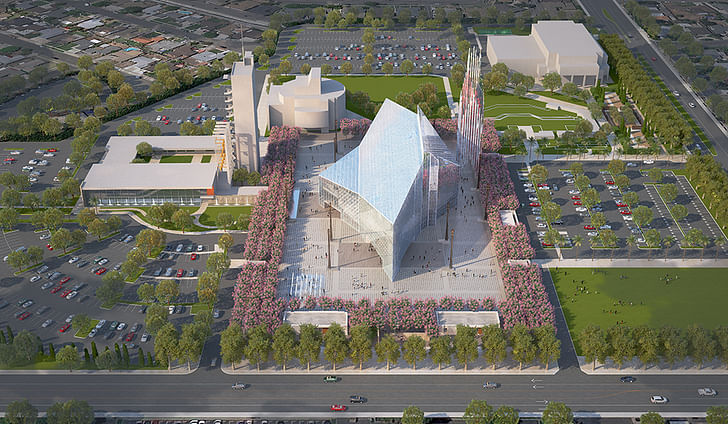

How does one design tangible structures for that most intangible of qualities, faith? More to the point: how does one renovate an existing place of worship to suit a new dogma? Johnson Fain’s renovation of Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s Crystal Cathedral is the culmination of metaphor, media, and the historical Christian tradition of repurposing.

Televangelist Robert Schuller of the Reformed Church in America didn’t just have faith, but a media savviness: he realized in the 1950s that religion, like any consumer product, could be shared far and wide via new technological mediums. Schuller briefly held court in a drive-in movie theatre, where parishioners could get the stereophonic good word in the comfort of their own automobiles. He then hired Richard Neutra to design a religious sanctuary, known as the Tower of Hope, for classroom and office space. However, the Church quickly outgrew the Tower. By the 1970s Schuller had engaged the openly secular and gay Philip Johnson to design a brand new home for his Hour of Power television show and congregation. Completed in 1980 in Garden Grove, California, the resulting massive glass building would officially become known as the Crystal Cathedral.

During the late 1970s, architect Scott Johnson was employed by Philip Johnson (no relation), and spent time working on the design of the glass skin of the Crystal Cathedral. When the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange purchased the building from the bankrupt Crystal Cathedral Ministries in 2012, they asked Johnson, now one of the partners of Johnson Fain, to renovate a building with which he was already quite familiar. The $72 million dollar renovation is scheduled to be completed in 2019; the building’s official new name is “The Christ Cathedral.”

I’m not even certain if they were aware that I had worked for Philip JohnsonSo what was it like to renovate a building he had fleetingly helped to initially design? I called Scott Johnson and asked him if remaking the Cathedral presented any personal conflict, or if it was merely strange. “No conflict—there was no negativity to it—it was your word, ‘strange,’” he explained. As a young man working in New York for Philip Johnson, Scott was experiencing an introduction to the profession and the joys of problem-solving. He has now lived in Los Angeles for about thirty years, and his New York past had become a distant if pleasant memory until he received a phone call from the Roman Catholics. “It was a little odd, or certainly unanticipated, when we had calls from the church asking if—and I’m not even certain if they were aware that I had worked for Philip Johnson. I think they were calling Johnson Fain among some other firms. And then I explained to them that they didn’t have to tell me about the building, I was plenty familiar with it. If they wanted to talk about where this building fit in with Philip Johnson’s chronology of work, I could tell them that too, so that was entertaining actually.”

What’s striking about the renovation is the meticulous balance Johnson Fain has achieved between respecting the original intent of the building while meeting the needs of its new owners. I wondered how the process of transforming a non-traditional worship space into a Roman Catholic orientation had unfurled.

“We went through several design phases,” Johnson told me. “At one point we were looking at an antiphonal situation where the altar would be in the center of the space. The building plan, as you probably know, is a long diamond east to west. You enter on the south, so it’s a very wide building and a fairly shallow building which is of course the opposite of a Roman Catholic basilica or cathedral, which tends to be long in the nave and then narrow in the transepts. That was an interesting characteristic of the building to adapt to Roman Catholic cathedral.” Eventually, Johnson Fain decided to orient the altar so it was sited off center to the north, so the parishioner seats would radiate around it, thereby allowing a priest to administer to everyone without ever turning his back on anyone.

However, the most inventive architectural element within the design is the quatrefoil, a translucent cloth window application that mitigates light, heat, and acoustical problems. The church’s all-glass exterior and lack of indoor cooling could make sitting in the pews during the summer an excruciating, sun-intensive experience. Meanwhile, the physical length of the church gave rise to a problematic two to four second frequency period for music and speeches. But how would these issues be resolved while preserving the iconic glass exterior?

“The issue was how to contain this Roman Catholic church, which historically has been masonry, while we have a completely glassy space,” Johnson said. “As we were charting and identifying the technical problems, we were also looking for an attitude, another layer to respond to the enclosure system that Philip and Schuler had created. There was the idea that looking out to the sky was the heavens but there were many metaphors for heavens, and so I basically developed the quatrefoil, which is a triangular section of light fabric that’s translucent, it’s not opaque.”

in a metaphoric way they are still like the heavens or the sky or the universeUsing a computer, Johnson Fain mapped all the panes of glass and then did a multi-season glare study. This allowed them to decide how to best distribute the quatrefoils, both metaphorically and pragmatically. “[The quatrefoils are] random, so when you look up at them they’re the seeming randomness of the stars in the sky, so in a metaphoric way they are still like the heavens or the sky or the universe, but in a different way. In a sense, we built a ship inside a ship, or a building inside of a building. I didn’t want to do anything to the exterior of the building; it’s largely identifiable by people from all over the world, it’s pretty much celebrated. That was an important part of Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s career. We wanted it to be the identifier of the project. So we’re in the process of restoring that. But once you enter, everything has changed, as if it’s a new building within an older building.”

This notion of the past being contained within the present is not merely an echo of Johnson’s personal history to the building, but the larger tradition of Christian worship structures in general. Johnson related to me a brief history of Christian gatherings; first, they met in burial sites like the catacombs, and then upgraded to basilicas, some of which began as Roman spas. Eventually, Roman Catholics started to develop their own architectural lineage, but as Johnson reflected, “the Roman Catholic story is about occupying spaces that they didn’t necessarily initially conceive. So it didn’t seem like a far conceptual stretch to say, ‘We have this building and it was for an Evangelical pro-ministry in the 1970s and 80s, but now it’s a Roman Catholic cathedral, how do we do that?’”

Looked at one way, the Christ Cathedral is a tame if pragmatically innovative renovation of an iconic structure that was initially meant to push past the boundaries of old school religious thinking. Once the temple of a television preacher, the cathedral now emphasizes a connection with a deity who will not be televised. All the same, Johnson was philosophical about the value of repurposing spaces and the associated conceptual challenges. “It’s a good architectural problem to use something that was there and has value and insert your own, new day in a way that’s still friendly to the old,” Johnson told me. “I think we, as our cities densify, that’s the kind of problem we have to think about a lot. You want to do something in your own time in your way with your own program to be relevant; at the same time you have this remnant, this earlier ancestor, and you don’t want to destroy it, you want to elevate it and acknowledge it. That’s a good kind of conceptual problem.”

This feature is part of Archinect's December editorial theme, Faith.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

3 Comments

Nice building. Good work. Did the church buy the entire facility?

The Crystal Cathedral can be seen in it's old glory days and is available through a rarely seen volume. We are the exclusive distributor for the Knights of Columbus.

ps: Yes they bought the entire facility

We, at DJL Audio Video Specialists, were tapped to renovate the audio / visual systems in the Arboretum, The Galleries and Freed Theater. We can't wait to see how they are going to approach the sound reinforcement, and possible video systems in the Crystal Cathedral proper. It has always been a problematic room acoustically, and has hosted some very leading edge technology, with very mixed results. Hopefully they will finally get it right this time around!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.