It all started January 2010 when I first interviewed the director of International Architecture Biennale of Rotterdam George Brugmans for Archinect. Since then, our relationship developed and I closely followed his work at IABR which I find arguably the most serious biennale concerning urbanism and city-making at the highest level of reality and usefulness.

I wanted to cover and continue our series of interviews when I sent George this question to just start the conversation: “I would like to ask a brief synopsis of IABR's beginnings and accumulation of its knowledge and actions, the cities and the environment? Perhaps a self evaluation of its operations from its director.”

A few months later I received his response.

After waiting for the whole media attention to die on the more touristic uncle in Venice, I think it is an appropriate time to publish the answer: "It's the culture, stupid!"

IT’S THE CULTURE, STUPID!

by George Brugmans

Culture is where we imagine, where we create the narratives that bind us together and that enable us to look forward. In plain English, spinning a good tale can get you somewhere. I learned this long ago, when as a student of History I embraced—among a lot of other, not always very helpful ideas about change and progress—Georges Sorel’s notion of myth as the motor of social change. I wanted to understand how cultures and societies change over time, and not as a result of drift but of action. How is it done, and what is needed?

I think the idea of design may well be facing one of the most compelling paradigm shifts in history.This was not long after May ’68, when students took to the streets shouting l’imagination au pouvoir!—the power of imagination would lead all of us to a better future. What I took from it was that where consciousness and society interact in a creative and willful way, that is, in the sociocultural space, new narratives are born that help us shed old paradigms and meaningfully ask: What’s next?

Now, 40 years later, I know that spinning a good tale is only half the story. When it comes to telling the tale of future cities, to imagine the making of city, IABR’s persistent theme, a convincing imagination, though imperative, is certainly not enough. For the narrative to endure and have real impact, for it to be not just told and visualized but also tested and amended, to eventually have an impact in the real world, we need another tool as well. That tool is design, and more specifically research by design, a tool with which the act of imagining the future can be transformed into constructively re-imagining it: What could be next?

That is, I hasten to add, only when we are ready to rethink the notion of what design would need to be for our day and age. In A Cautious Prometheus?, a speech he delivered in 2008, French theorist Bruno Latour observed that "design as a concept implies humility that seems rather absent from the word 'construction' or 'building' . . . and that is completely lacking in the heroic promethean hubristic dream of action." He welcomes the "remedial" in design as ". . . an antidote to hubris and the search of absolute certainty, absolute beginning, radical departure." It’s from this position, this remedial perspective if you want, that I think we need to challenge the often still-prevailing notion of design. It should no longer be a quest for beginnings and departures, for grand gestures and blank slates, the architect’s imagination roaming freely. To design would be to want to depart from a given or a problem, to look at the emergent, unplanned, unstoppable process that lies beneath it, and to turn it Into something more vibrant, more viable, more usable or user friendly—and more resilient. To design would not be a process of heroic imagining but of explorative re-imagining. Re-imagining, discovering what could be next for our future cities, is a pertinent exercise. And I think the idea of design may well be facing one of the most compelling paradigm shifts in history.

Presentations of Smart Cities for instance more often than not look a lot like the science-fiction movies we’ve seen years ago.Ongoing globalization and urbanization, climate change, technological and scientific advances and convergences, and so forth, are rapidly changing how we live and interact. The speed of change is growing exponentially. But the way we now imagine our future cities is mostly still very outdated. Presentations of Smart Cities for instance more often than not look a lot like the science-fiction movies we’ve seen years ago.

We are going to have to come up with something really different. We have to leave behind us the big wasteful aggressive systems we can now see for what they are, creation and construction predicated on eternal economic growth. While what tomorrow’s cities urgently need are new feedback loops with deep implications for the relationship between user and designer, and between user and user. We must move from wasteful to sustainable consumption, and from linear to circular production systems that are regenerative by intention and design. We must move from creating systems to mending our ways.

And mend our ways is what I think we have to do, and sooner rather than later. The future is now; it’s the mess we have to make sense of. So what’s next and what could be next? Clearly, culture and design make for a potent mix when it comes to re-imagining our future cities. Which is why it is the crux of the IABR’s very own methodology for making sense, for making city.

So let me clarify why I think that it’s the culture, stupid!

Inside Out

Francine Houben, in 2003 the first IABR’s director and curator, straightaway positioned the event as a research biennale. As curator she did her own research and she cleared space on the IABR’s international stage for research projects from all over the world, emphatically putting the Rotterdam architecture biennale on the map.

The exhibition became a means and its subject—the city, where plans and projects materialize after the closing of the biennale—became the object.Since 2004, when I succeeded her as director, I have been turning this model inside out together with successive curators Adriaan Geuze, the Berlage Institute, Kees Christiaanse, Henk Ovink, Fernando de Mello Franco, Joachim Declerck, and Dirk Sijmons. Rather than being a goal in itself, the Biennale as an international exhibition increasingly was integrated into the research by design process. The exhibition became a means and its subject—the city, where plans and projects materialize after the closing of the biennale—became the object.

I felt it was a waste to not better exploit the remarkable variety of knowledge and expertise that our growing global network biannually brought to the Rotterdam stage. Why not connect all the knowledge we ourselves accumulate to the knowledge of our network; why not apply the collected innovation-oriented expertise to existing challenges? Why not conduct research by design ourselves, in places where we have already established a basis for trust as a cultural organization?

Sabbatical Detour

Over the last ten years, with input from many people, one biennale at a time, IABR has gradually developed a new methodology. Rather than travel the world just looking for the best projects, we more and more often stick around and join in, to reflect and work on local challenges. We have engaged in the project of the city itself. We are no longer satisfied to only show the best plans and projects. We also want to add value, inform existing projects narratively and programmatically, by taking them on a "detour" through the cultural space, together with the city and all stakeholders.

We call this methodology the Sabbatical Detour, a term I coined while analyzing the first detour—from 2008 in and with the city of São Paulo in the favela Paraisópolis –during my first interview about the IABR methodology, with Orhan Ayyüce for Archinect: It was the right mix of the right people in the right place at the right time. We had liftoff before we even The Biennale is used to take the project on a detour, literally: a sabbatical.really truly realized we were working on a very real and concrete project in the sense that it was going to be implemented. To make a long story short, when we finished the project that we’d done together with the municipality and when the Brazilians decided to implement, to spend 400 million reais on what we’d contributed to, I looked back and realized that what we had in fact done had the makings of a new working model. I dubbed it the "sabbatical detour model," because what it does is it lifts an urban challenge, an existing project, temporarily out of the killing fields of local politics and the business-as-usual approach. The Biennale is used to take the project on a detour, literally: a sabbatical.

In every respect, it was indeed the ‘right mix of the right people in the right place at the right time.’ The Brazilian economy was doing extremely well at the time. Unemployment had dropped and people felt increasingly safe in the streets. The favelas were no longer merely no-go areas and millions of people could join the middle classes. There was money and there was optimism, especially in São Paulo, the motor of the Brazilian economy. Doors opened and there was more room for experiments. But how do you conduct experiments with the biggest city in the Southern hemisphere?

Elisabete França, the director of São Paulo’s social housing department SEHAB, was open to new ideas and municipal councilor Elton Sante Fé Zacarias supported her. The favelas attracted artists and architects from all over the world, but what distinguished the IABR is that we came in as a biennale, yet went to work as designers. This allowed for a genuinely new approach, especially with a design team consisting of young, talented architects including Fernando de Mello Franco, Alejandro Aravena, Alfredo Brillembourg, Hubert Klumpner, Christian Kerez, and Rainer Hehl, who coordinated the process locally.

The result was three-fold.

The Paraisópolis project generated concrete proposals that were exhibited in Rotterdam, São Paulo, and elsewhere. Not only did SEHAB decide to implement the proposed projects, the collaborative process also changed the department’s perspective on its own challenges and methodology. Maria Teresa Diniz, project manager of the Paraisópolis project:

The collaboration proved to be much more intensive and productive than a mere exchange of ideas. We discussed the role of architects and urban designers, how their work might contribute to a better life in the city, to a much broader perspective. In the beginning we were not at all familiar with the IABR’s working model: a test site where the work is already in progress? When Paraisópolis became a laboratory for the Open City, however, it proved extremely fruitful to discuss the way we work with experts from other parts of the world. Our methods were examined, and this forced us to reconsider and adjust them.Was our São Paulo tour de force reproducible? If so, how and where?

My conclusion, from an IABR perspective, was that it looked as if the collaboration had yielded a new methodology: the Sabbatical Detour. Still, lots of questions immediately arose. Was our São Paulo tour de force reproducible? If so, how and where? What conditions—political, economic, cultural—were prerequisite? Would the method depend on finding the right people—politicians, administrators, designers—or could we use it anytime, anyplace, anywhere? Was the Sabbatical Detour a genuine city-making tool or did we owe Paraisópolis to our lucky stars?

I decided to use the next Biennale to examine the validity of the Sabbatical Detour methodology.

Making City

The 5th IABR: Making City (2012) was a quest for new ways of making city. Alternative practices from around the world assembled in Rotterdam to present and exchange knowledge. One of the crucial questions raised was about the relationship between design and politics and the role the cultural space played in that relationship—the crux of the Sabbatical Detour. I asked Belgian architect Joachim Declerck, with whom I had often discussed these topics, and Henk Ovink to join the Making City Curator Team. Ovink, at that time the director of Spatial Planning with the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, was already conducting a similar study of his own, called Design and Politics.

All three of us felt that that the city-making challenge ought to be at the center of the social and political debate about our future. We wanted nothing short of turning "to make city" into a new verb. We were looking for a new balance between governing the city and transforming it; between politics and design, and we wondered whether it was actually possible to field-test new ways of making city, whether regular routines still had the space and the resources available to do so. We wanted to find ways to re-inform institutions with adaptability and flexibility, with appreciation for the potential and the effects of the transformation process itself and the ability to invent, to re-imagine. And we wanted to know what part the free cultural space, where creativity, letting go, and trying over and over again are important tools, could play in the process.

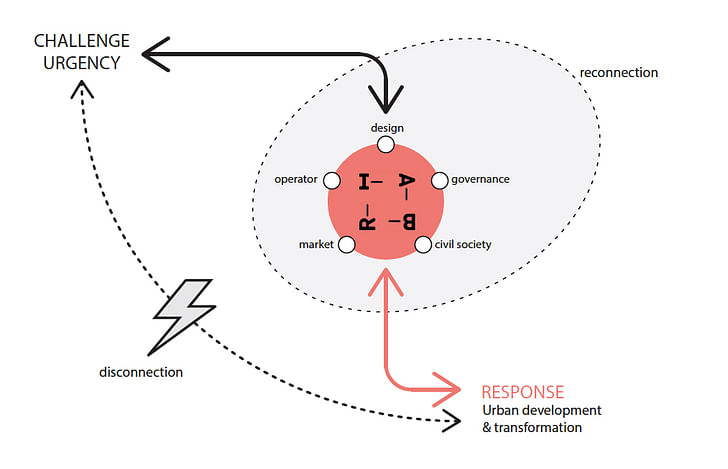

One of the major issues we addressed in Making City was therefore the tension between design and politics. If business as usual no longer functions, or not properly; if there is interference on the line between challenge and practice, then the development of alternative practices is necessary for us to make a sustainable city. Can a Sabbatical Detour through culture actually be such an alternative practice?

Test Sites

Making City centered on the testing of the validity of the Sabbatical Detour. This actually took place on three Test Sites. In São Paulo we once again collaborated with SEHAB; Fernando de Mello Franco was the local curator. This is where we first established a relationship between spatial design and the economy, sowing the seeds of the rudimentary research questions I developed in 2012 together with Declerck for IABR–2016–THE NEXT ECONOMY.

In Rotterdam, the Schieblock project initiated by ZUS—in which the IABR had been involved for quite some time—became the center of Test Site Rotterdam, one of the Biennale’s two main Rotterdam venues. The Schieblock was lifted onto an (inter)national stage. ZUS turned Test Site Rotterdam into a project that became a much-discussed Dutch example of how we can also make city bottom up, incrementally, and by modest interventions, especially in times of crisis. In Rotterdam, "making city" actually became a verb.

It is a safe place to think out of the box; to let go of opinions and interests for a momentIn Istanbul, we signed an agreement with the municipality of Arnavutköy; Asu Aksoy was the local curator. Here, we both developed a project the municipality later embraced and sowed the seeds for an extremely fruitful research by design trajectory on the "urban metabolism", further developed by IABR–2014 curator Dirk Sijmons in URBAN BY NATURE and expanded on in, among other places, Rotterdam and Albania.

Good, clear results, but it wasn’t plain sailing all the way. In Rotterdam, we encountered a lack of genuine political commitment; in São Paulo the final days of a political cycle, when officials begin to focus on their legacy rather than new ideas; and in Istanbul a complex web made up of political interests and procurement practices. Design and politics, indeed!

Safe Place for Dangerous Ideas

An important added value of the cultural space is that various parties, interests, agendas, and perspectives can be assembled around a difficult issue. It is a safe place to think out of the box; to let go of opinions and interests for a moment; to shake off the burden of existing legislation, political infighting, and prying media temporarily in order to work out how to move forward together.

The cultural space is where we create the narratives that bind us together and that enable us to look forward: What do we want? And research by design is a specific way to study the future, one that allows us to ask: What can we want?

exactly because we operate in the cultural realm, or seem to operate strictly in the cultural realm, we offer the political institutions a special zone, a safe havenThe cultural space is a safe place for dangerous ideas that can make a real difference, as I concluded when Orhan Ayyüce once again interviewed me for Archinect after Making City: we opted for interacting with the real world, for pushing to the limit what a cultural operator such as the IABR can really do. And one of the things we can do is to identify and support innovative practices, put them on a platform and call on municipalities and institutions and what have you, to get on board with us and find out what the potential of these new alliances for meaningful change is. Can we scale them up? Can we do it together? . . . And exactly because we operate in the cultural realm, or seem to operate strictly in the cultural realm, we offer the political institutions a special zone, a safe haven where they can have an open brainstorm, think in a less risk averse way, where they can rock and roll and connect to new ways of thinking.

Rock and roll, but with real commitment and an insistence on applicable results, even while the dance continues. Implementation should always be the goal of the Sabbatical Detour. It is a detour, but it does lead somewhere: What will we do? Used in conjunction, cultural space and research by design are therefore really powerful tools for incremental work on the future of the city—however, only if the process is linked smartly and effectively to the process of political policy- and decision-making.

My main conclusion was that the method was valid; that it could be applied in multiple locations and under different conditions—that a detour via culture can create genuine added value. It was also clear, however, that to generate sufficient political commitment, the administrative anchoring of the projects needed to be much more firm, with an insistence on implementation, since this is prerequisite to activate the government apparatus itself.

Ateliers

Making City took place from 2010 to 2012, when the financial crisis was making headlines every other day. As it turned out, urban development was highly susceptible to the crisis, even partly caused it, and the city-making process halted. But especially when things do not come naturally, there is a need for an innovative and alternative practice. That is why I decided to turn the IABR inside out completely, with one last pull. It was time to hit the highway with our detour.The IABR has definitively crossed the threshold and has become a city maker as well as an exhibition maker.

What had been developed on the Test Sites was now made the centerpiece of the IABR project. All research by design was accommodated by our own IABR–Ateliers, long-term research by design trajectories in which the IABR, in a collaborative commissionership with a (mostly urban) government, temporarily detours an existing challenge through the free, cultural space to develop innovative, concrete, and applicable solutions.

The IABR has definitively crossed the threshold and has become a city maker as well as an exhibition maker. Having been appointed lead partner of the national government in 2013, with the assignment to employ research by design for local and regional challenges in the Netherlands, the IABR was effectively in a position to cross that threshold and establish Ateliers in collaboration with the municipalities of Rotterdam, Utrecht, and Texel, and with the provinces and cities in Groningen and Brabant.

These IABR–Ateliers were administratively much better anchored than the Test Sites, which immediately made the collaboration with the authorities more intensive. To generate actual commitment and hold on to it—not only during the collaboration itself, during a government’s involvement in the Biennale, but especially with regard to eventual implementation—it was inevitable that we began treading the lengthy corridors of the administrative apparatus.

Capacity Building

One of the key questions of Making City, how to re-inform institutions with adaptability and flexibility, with appreciation for the potential and the effects of the transformation process and the ability to actually innovate, was increasingly at the forefront. In many Ateliers, the focus of the research by design shifted from the right strategic plans and projects themselves to the question of how to establish any new practice at all. Capacity building, All in all, many cities are organized effectively to manage yesterday’s problems; or today’s at besttoolboxes for governance, development principles that allow for incremental, learning by doing, and sector-transcending work on complex challenges became important products of the Ateliers.

It is precisely these more complex and often urgent challenges that governments usually find difficult to manage. Urban development is regularly left to the market. What remains is an approach increasingly harnessed by routine and regulations, procedures, and process management. All in all, many cities are organized effectively to manage yesterday’s problems; or today’s at best, while testing methodologies, over and over, and constantly making adjustments is essential when it comes to solving the problems of tomorrow. Urban development is a work in progress.

In Atelier Albania the IABR, in collaboration with others (among them the Brussels architecture firm 51N4E), and commissioned by the national government, has conducted extensive research into the metabolism of Albania as the crucial foundation of proposals towards a sustainable spatial development model for the entire country. The national government has embraced the necessity of an integrated approach and analysis of metabolism, and included it in new policy documents. However, the real work still has to be done. How can policy documents be linked to reality? The core of our recommendations is to have the sustainable development process go hand in hand with the bottom-up Success ultimately depends on how governments as well as designers handle the potential of the free cultural space—or rather, whether they can handle it.restructuring of national planning—varying from new training programs to a different organization of the government apparatus and ministries. The National Planning Office had best merge into Atelier Albania.

The goal of the Atelier is to foster a culture of learning by doing, of national planning as a continuous work in progress, where planning becomes a strategic feedback loop that produces applicable plans and projects that in turn inform the process of planning, and so forth. A reiterative and incremental research by design trajectory that builds capacity and that takes place in an open learning environment.

To take the entire country of Albania on a Sabbatical Detour: that is the ambition.

The Sabbatical Detour is eminently suitable for capacity building. To architect Fernando de Mello Franco, a member of the Making City Curator Team and now the City Councilor of Urban Development in São Paulo, the primary objective of his collaboration with the IABR may well be to make sure that after his term in office is over, his staff will know how to use research by design in day-to-day practice. "It it is necessary to promote shared work processes between the day-to-day efforts of government and autonomous research initiatives. Exactly there, in the space in between, lies the value of the opportunity offered by IABR’s methodology," he writes elsewhere in this catalog.

Critical reflection on what will and what will not work in that "space in between"; what the conditions are under which the Sabbatical Detour will allow design and politics to actually work together in a free and at the same time genuinely targeted manner, remains part of the method itself. The IABR is a learning organization. But of course the Sabbatical Detour will never result in standard procedures for finding "the right mix of the right people in the The development principles work like castor oil, and there is awe and respect for the fact that as an island, we dared envision our future.right place at the right time." Success ultimately depends on how governments as well as designers handle the potential of the free cultural space—or rather, whether they can handle it. If designers succeed in using the power of re-imagination to provide an alternative action perspective, if all parties are real stakeholders, if the officials are truly committed, and have the government apparatus eager to get started on realizing that perspective, the Sabbatical Detour is a success. Like on Texel, where aspirations and opinions firmly collided initially: economy versus spatial quality; sustainability versus touristic product. But the IABR Atelier Planet Texel became a success, because it eventually succeeded in uniting politicians, officials, entrepreneurs, residents, and designers in a single ambition for the future that could be owned by everyone involved. The combination of a compelling shared narrative, quality design proposals, and committed administrators yielded sustainable development principles that were unanimously embraced by the island council, because they allowed 15,000 islanders to incrementally and democratically invent the future that they, themselves, wanted. Island councilor Eric Hercules:

We now have a structural budget available to address sustainability on the island and we have budgeted over 2 million euros to begin in De Koog. The commitment is unanimous and complete. The development principles work like castor oil, and there is awe and respect for the fact that as an island, we dared envision our future. Other authorities, the Dutch National Forest Service, the Waddenfonds, and Natuurmonumenten are very taken with the process on Texel. The other Wadden islands emulate the principles. Internally, the dialogue has changed as well. When policies are made, all of the sectors take the principles to heart. They are being incorporated in a policy document on recreation and tourism and the principles are a guideline for all policy considerations.

The Challenge

I am convinced that alternative practices, such as the Sabbatical Detour and of course many others, are imperative because more and more lights are turning red.

The city is the most complex artifact our civilization produces, but the speed with which we produce it has increased exponentially over the last 50 years. Really, no one has a clue we know what’s at stake: no less than, in the final analysis, the whole of the planet fit for human life.how to create sustainable cities for billions of people. The New Delhi population, for instance, is expected to reach over 90 million by the end of this century. How do you make a city for 90 million people, let alone a sustainable one? Nobody knows. Additionally, we are forced to rush into a post-fossil era, a new age in which even nature is no longer a matter of fact but has become a matter of concern instead.

Let me quote Bruno Latour one more time: "The more matters of facts are turned into matters of concern, the more they are rendered into objects of design through and through."

The ambition is to use the power of design, of the re-imagination, as effectively as possible in a series of ever more complex challenges in a time of ever-accelerating transitions. The complexity and the urgency of the design challenges, from New Delhi to Rotterdam, require that everyone is willing to learn as quickly as possible, build capacity, and explore and field test as much as possible as quickly as possible. That is where we have our work cut out for us. From matters of fact to matters of concern.

The future is now: it’s the mess we have to make sense of; the challenge we face. We know the playing field and we know what’s at stake: no less than, in the final analysis, the whole of the planet fit for human life. We know what the name of the game is and we are aware that the endgame has in fact already begun. Yet the rules of the game still There won’t be a time when the city is once and for all done to perfection. There’s always something that’s next.escape us. And that is a problem, because the rules appear to be in a permanent state of flux. There won’t be a time when the city is once and for all done to perfection. There’s always something that’s next. How do we get from "coming up with plans and solutions" to "working with the ongoing transformation of day-to-day reality?" Which development principles will keep us on the smartest track toward an ever-uncertain future?

We have to learn to change our minds about how we change our minds—institutions, too.

Therefore, alternative practices, such as the Sabbatical Detour, have great value. What do we want? What can we want? What will we do? I am convinced that the free and creative space that culture offers society represents an enormous potential for real innovation. We will continue to use that free space to the max. It’s the culture, stupid!

I want to thank Orhan Ayyüce for the space and time he gave me to collect my thoughts for the two interviews with Archinect from which I drew for this essay, and Marieke Francke and Henk Ovink for always critically reading my work. — George Brugmans

A long-time contributor to Archinect as a senior editor and writing about architecture, urbanism, people, politics, arts, and culture. The featured articles, interviews, news posts, activism, and provocations are published here and on other websites and media. A licensed architect in ...

No Comments

More from Failed Architecture on IABR:

What's An Architecture Biennale Good For Anyway? (read the whole article here)

Critically yours

While it’s not very common for architecture biennales to organise their own criticism, that’s what this year’s International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR) has done. In the early spring, we were asked to be this year’s ‘critics-in-residence’ and reflect on the ideas, projects and outcomes of the biennale in a series of essays. After an introductory reflection on this role, we started with a written extrapolation of the future techno-dystopia presented in the VR-installation at the entrance to the biennale, arguing that the future city might indeed look like this ‘if we don’t change course’. Then, we distilled the most important threads from the biennale’s exhibition, which can be read as a broad outline for an alternative way forward with respect to this looming dystopia.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.