What makes a truly smart city? Just as importantly, how do designers help revitalize older urban cores without repeating past mistakes that led to displacement and inequitable urbanism? These are some of the questions raised in Andrew Bruno's master's thesis project for the New Jersey Institute of Technology, submitted to May's open-call for equitable architecture proposals.

Bruno argues that parking, that old disperser of 20th century urbanism, should not be a key component of Kansas City's new metropolitan initiative. Instead, he proposes a series of multi-tiered living and working arrangements built on existing city parking lots which foster a distinctly more centered, and technologically-enabled, mode of existence.

Like a Wi-Fi-enabled version of the 1862 Homestead Act, under Bruno's proposal Kansas City would grant "unprogrammed cells" to applicants who wished to make a go of it in this new urban frontier. In his project statement below, Bruno contrasts his vision of the smart city with Kansas City's real-life proposal.

From Andrew Bruno:

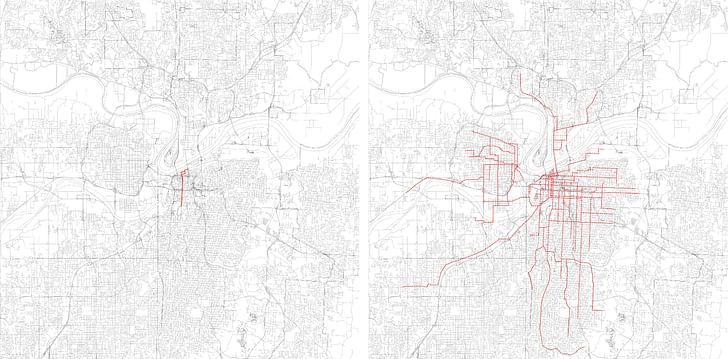

Kansas City, Missouri is home to the United States’ first coherent smart city initiative. A two-mile stretch of downtown KC is in the process of being outfitted with a sensing apparatus that will provide residents and visitors with information ranging from events taking place within the city to the locations of available parking spaces. The project is a public-private partnership with Cisco (which is also providing the hardware), and is promoted breathlessly as a major component in Kansas City’s impending renaissance.

different forms of living and working are envisioned as a result of the critical application of certain smart city technologies.The project, however, does little to address KC’s larger issues that have been brought about by its radical dispersion (Kansas City is about an eighth as dense as Staten Island, NY). Ironically, the system’s “smart parking” component actively encourages a continuation of the automobile-driven urbanism that has led to KC’s dispersed condition. In fact, a cursory study of the major players in the smart city game—like Cisco, IBM, and Siemens—reveals that the primary motivation of any contemporary smart city project is to enable a streamlining of the existing modes of economic production that have given rise to the dispersed patterns of urbanization that characterize American cities like Kansas City. Smart city proposals like KC’s will thus always stop short of envisioning the new ways of living and working that may be enabled by the technological instruments of the smart city. “Homestead” imagines a scenario in which Kansas city decides to reclaim a territory within its downtown that is currently inundated with mostly city-owned surface parking lots, and to use this territory as a test bed in which different forms of living and working are envisioned as a result of the critical application of certain smart city technologies.

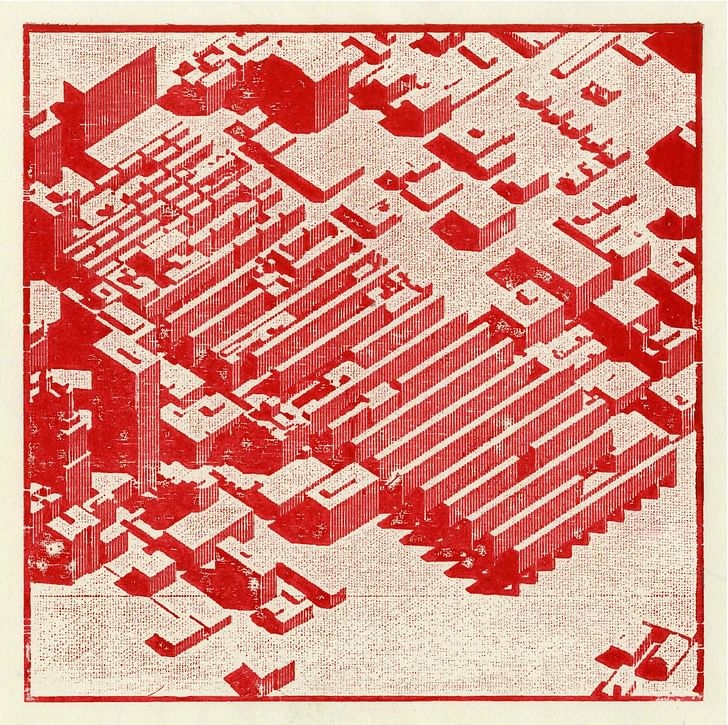

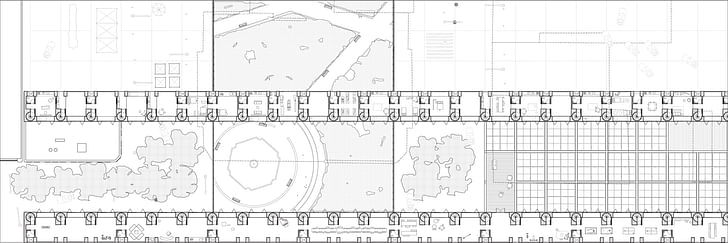

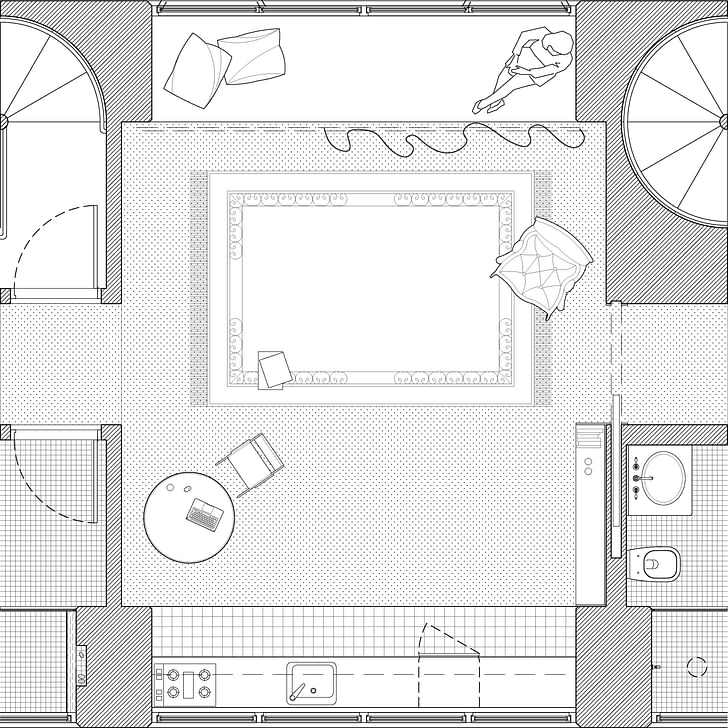

A grid of unprogrammed cells is lofted in bar buildings over a continuous, minimally obstructed and hyperactive ground plane in which pedestrians and autonomous vehicles co-exist. Inscribed on this ground plane are spaces for public communal work, enabled by ubiquitous wireless internet access. Below the ground surface is a network of sunken gardens into which residents of the territory may collectively escape for a respite from the frenetic activity of the ground plane.The ultimate aim is a relief of the pressure of securing living and working space

“Homestead” imagines this territory being a zone of opportunity for individuals and families to claim space for their personal pursuits. In a mirroring of the Homestead Act of 1862, in which applicants were granted tracts of federal land by the U.S. government, this project imagines Kansas City granting applicants a number of unprogrammed cell spaces within this newly reclaimed territory.

These freshly claimed spaces can be used for living or work, but like in the original Homestead Act, new residents would need to prove an improvement to the spaces upon which they lay claim. Certain areas of the hyperactive ground plane are likewise available for apportioning and individual improvement. The monitoring and automation techniques of the smart city can thus be put to productive use in the administration of this complex system of spatial apportionment.

The ultimate aim is a relief of the pressure of securing living and working space in order to free citizens of Kansas City to pursue a higher level of productivity for themselves.

This piece is part of Archinect's special May 2016 theme, Help. How can architecture help create more equitable societies? More related news here.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.