The Charles Rennie Mackintosh building at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) is an iconic structure and home of one of the greatest art schools in Europe. The building, voted the best British-designed building of the past 175 years in a nationwide poll conducted by The Sunday Times newspaper and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 2009, is an iconic role model for what we perceive as the ideal art school: a space that exudes creativity through design, atmosphere and craft.

"The Mac" as it is affectionately known, is a much-loved building, close to the hearts of not only students, alumni and architecture fans, but also those that live and work in its shadow.

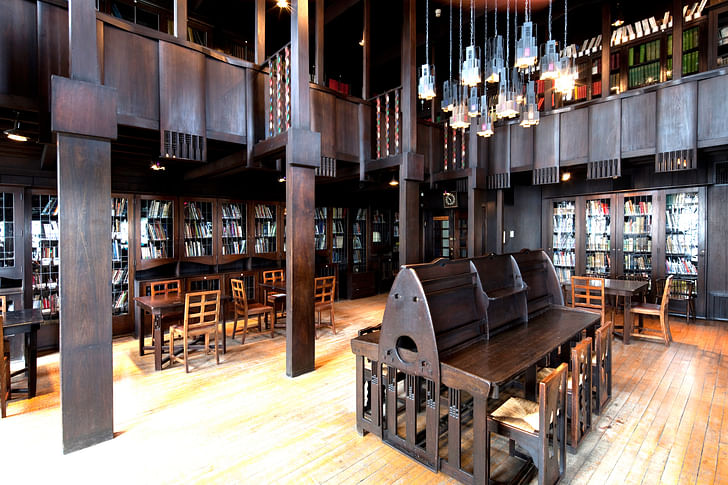

On May 23rd, 2014, tragedy stuck. During preparations for the end of year degree show, a canister of expanding foam was left too close to a slide projector in a ground floor studio. Heat from the projector ignited gases from the expanding foam, the flames quickly spreading up through the air vents and spaces between the wooden panelling, shooting up through the top of the building and out through the roof. Many parts of the building remained completely unaffected by the fire, while others, including the library, the jewel in the crown of Mackintosh’s vision for GSA, were completely destroyed.

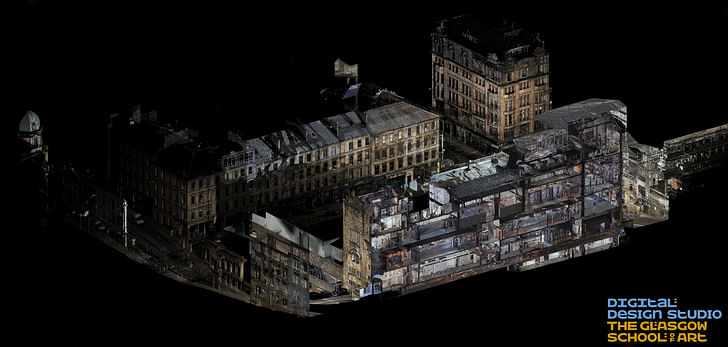

Glasgow was a city in mourning. The day after the blaze, the Financial Times newspaper quoted RIBA describing the blaze as "an international tragedy". Luckily, though, much of the building remained intact. The blaze, although ravaging much of the interior, had not destroyed the foundations. Roughly two-thirds of the building were left relatively untouched. However, despite this good news, the damage was enough to render the building unusable until restored: the college was forced from its home.

the user begins to realise that there is more to the building than meets the eye.Immediately the campaign to rebuild started. Actors Peter Capaldi (an alumni of the school) and Brad Pitt helped to increase the profile on the initial campaign by GSA to raise £20 million, to which the UK government donated £5 million. And, when the insurance pay-out finally goes through this month, Page\Park Architects will start the restoration work that they’ve been preparing since the blaze.

Page\Park fought off competition from four other shortlisted practices, including London studios John McAslan + Partners and Avanti Architects, to be awarded the commission to lead design work on the restoration project, which will reportedly cost £35 million. The Glasgow-based architectural practice has wide experience of working with the building and was last commissioned to renovate the windows in its library, which were completed shortly before the fire.

I visited Page\Park Architects in Glasgow on the day that they met with GSA to reveal their latest research and findings, and then later, went on a site visit around The Mac with Liz Davidson, Senior Project Manager of the Mackintosh Restoration project.

Davidson took the floor at Page\Park Architects in an up-tempo mode. “This project is about taking advantage of adversity,” states Davidson. “There is providence in what happened. When you take a step back, the building has been brilliant. We’ve suffered a 16 or 17 per cent loss; people shown round don’t understand the loss, it looked like a malign fire, but we’ve saved a lot.” In other words, it could have been much, much worse.

Davidson then goes on to detail some of the losses including clocks, which were one-offs, and the light fittings in the library. The restoration details an “archaeology of debris”, including 603 pieces in the light fittings alone. Davidson offers up an interesting thought: “Perhaps GSA has a building that they don’t know, the user begins to realise that there is more to the building than meets the eye.”

Davidson is keen not to create a falsely rosy picture of events but states that the fire has had “a cleansing effect on the building, revealing helpful design processes” and that “attention to detail has been fantastic – the school has a real hunger for the research and development side of the building.” Davidson then goes on to explain the use of BIM in the GSA conservation work, a new tool to the UK in design and conservation work, and introduces Dr. Robyne Erica Calvert, Mackintosh Research Fellow, who is creating an archive of findings from the project.

Talking to Dr. Calvert about her role in the project clarifies the role of research in restoration. She states, “As the Mackintosh Research Fellow, my role is to capture and foster the research possibilities that arise from the reconstruction process, so not precisely to do the research for the actual restoration itself. That said, there is a great deal of overlap, and the team involved is very collegial.”Mackintosh's designs are strong enough that, if we manage a faithful recreation, we can, in time, achieve that quality again.

Dr. Calvert notes that, luckily, there was a large amount of research on the estate already conducted before the fire. Once Page\Park came on board, the team at GSA began working closely with their research team to determine the gaps in knowledge and prioritise the areas that needed more investigation. Dr. Calvert found herself working largely on the decorative scheme for key areas, including the library. Dr. Calvert explains “While the Mackintosh Building is an incredibly well-documented work, we very quickly realised that there was still some lack of clarity regarding the finer details of the space. In particular, the hand-carved elements of the library ornamentation were not always explicitly recorded. One of the projects I have focused on is an accurate recovery of these designs through examining a number of visual and textual sources.”

This attention to detail is not simply to replicate surface design. “One of the exciting challenges in this project is that we, of course, don't wish to simply reconstruct the schemes, but we hope to also approximate the atmosphere of the original interiors,” explains Dr. Calvert. “It could (and has) been argued that this ambiance has been forever lost in the fire; however, I would argue that Mackintosh's designs are strong enough that, if we manage a faithful recreation, we can, in time, achieve that quality again.”

Is it really possible to recreate the work of a truly remarkable and visionary master-craftsman of the past? “On what we’ve learned so far, I think it would have to be realised that the interiors were perhaps not as finely honed as they appeared to be on the surface,” notes Dr. a manner that left one feeling every detail was finely wrought, when the reality ‘under the surface' tells a much different story.Calvert. “Any anxiety that we now lack the kind of craft skills that were employed to create the building is very clearly unfounded – the fire has revealed that while the surface of spaces like the library appeared highly hand-crafted, this was actually a well-designed façade, and the actuality is that the room was pieced together like ‘tea room shop fitting’, as Ranald MacInnes of Historic Environment Scotland so aptly put it.”

What does Dr. Calvert mean by this? "Nails were hammered wherever they were needed and finished surfaces covered up rough and readily available materials underneath. The space was not so precious in its construction, made in a workshop off-site and assembled in situ, almost like we might use ‘flat-pack’ material today,” she explained. “We knew that a variety of local labour was used and that it wasn't made with the idealised ‘Arts & Crafts' approach that many assumed, but [the] beauty of the finished result belied this: seeing the evidence of all of it first-hand was still somehow surprising. It has given us an opportunity to reflect on Mackintosh and his working methods, and the way in which his mastery was about creating the ‘look' of space in a manner that left one feeling every detail was finely wrought, when the reality ‘under the surface' tells a much different story.”

The fire has given a fascinating insight into the working practices of Macintosh. Walking around the fire-damaged building I'm amazed at the fickle nature of fire. Some parts of the room that the fire started in remain completely untouched whilst others, several floors up, are completely decimated. The fire has stripped layers off the building; clearing the makeshift art school partitions that had remained “temporary” for decades, revealing walls used as slapdash palette boards and hidden rooms and cupboards behind plaster boards. The fire now gives GSA the possibility to update the facilities for its students and to make good the failings and quick fixes dating back years.

“It’s remarkably well-suited for the disciplines it set out to serve,” explains Davidson of the building, as we walk around the site. “It’s the one time to get it done and get it done properly and to do the best possible job. The college wants to talk about ways in which they can manipulate the building: we are talking about pedagogy taking advantage of the fire.”

Talking to Brian Park of Page\Park about the opportunity to rectify the issues that grew up over time brings forth the question, how far do you balance correction with warts-and-all authenticity? “We are addressing some fundamentally flawed details such as the junction of the north studios' flat lead roofs with the second floor studios' glazed screen,” says Park. “Quite simply, it’s a bad detail and we are working hard to adjust this to work much better this is not the place for an ego as we work with the genius of Mackintosh.without continued maintenance and are doing so in consultation with Glasgow City Council (as planning authority), conservation staff and also Historic Environment Scotland. We wish to minimise the visual aspect of any change. This applies in several other areas, but they are limited, and the building as a whole will be restored on a like-for-like basis.”

How are all the working parties making sure that GSA doesn’t merely becomes a museum piece, once it re-opens as a college and as a public space? “GSA have a very clear priority in that the building must serve its academic function as it has done, so well since it was built,” says Parks. “As with the conservation and access project, there is a careful balance between primarily academic teaching and studio use and limited visitor access facilitated by GSA Enterprise who have a tours programme. It will absolutely not become a museum piece but a building in full academic use.”

Heartening to hear, what then of the renewed legacy for the building? “I think the best legacy we can leave is that respect for different approaches to a project of this scope – encompassing historical, material, technical, and even philosophical and theoretical approaches – really provides for a rich and thorough outcome,” says Parks. “We are of course far from a final result, but we already have seen how well incorporating a variety of disciplines has assisted in furthering this project.”

As an architect working on a much-beloved predecessor's work, does the team at Page\Park find itself asking the question, “What would Mackintosh have done?” when it comes to building for the future? “The question arises in the studio here at least once a week as we work through all aspects of detail,” says Park. “And our experience of working on several other Mackintosh Buildings; my role as a past convert of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society and my recent involvement in surveying 22 Mackintosh buildings, interiors and monuments feeds that ‘getting-into-the-head-of’ aspiration. And David Page has also, quite separately, read and researched on Mackintosh for many years.”

No wonder then that Page\Park is seen as the ideal practice to rebuild the GSA. What then, is the end goal for those involved in the architectural side of the restoration project? To get GSA back to looking whole again. “Ultimately to deliver the building back to GSA enchained, where that is appropriate in terms of building services and lighting, but without it looking as any architect has been there. And I do mean that,” says Brian Park. “All architects have an ego, even if it is small, but this is not the place for an ego as we work with the genius of Mackintosh.”

Robert studied fine art and then worked in children's television as a sound designer before running an art gallery and having a lot of fun. After deciding that writing was the overruling influence he worked as a copywriter in viral advertising and worked behind the scenes for branding and design ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.