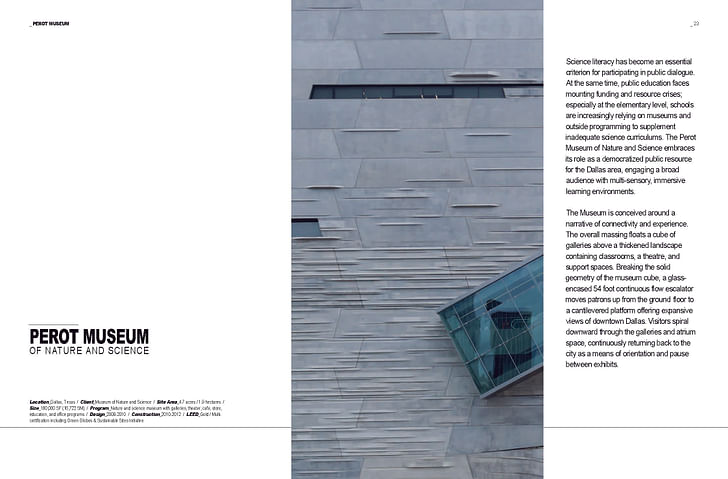

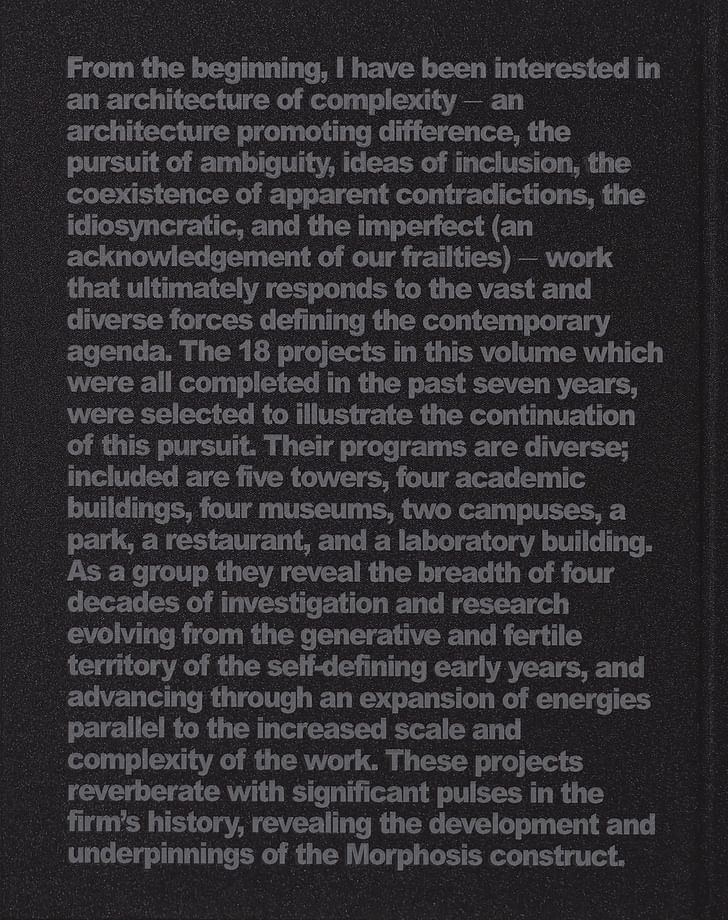

How does an architect tell his story? Thom Mayne, who spent decades struggling to put the idiosyncratic visual terrain of his imagination into relatable speech, has chosen to tell his story with ‘M.’ Ostensibly the latest monograph by Morphosis, ‘M’ is also in Mayne’s view a comprehensive tour of his sensibility.

His story is one of jazz, sex, and the alienation of singular genius. It’s about growing up alone and then embracing a society that was blossoming with artistic possibility. It’s about watching movements – modernism, an alarmingly radical political right – rise and fall and rise again over the course of five decades of practice. It’s about falling in and out of love with people but staying true to his work, and refusing to do what others expect, even when the money is tempting. Fundamentally, it’s about being an artist in the architectural realm.

At least, this is the nuanced (and lengthy) story 72-year-old Thom Mayne wanted to tell me, and did tell me, as we sat in his studio’s upstairs conference room. His story is one of jazz, sex, and the alienation of singular genius Mayne shifted fluidly between the first person “I” and the second-person “you” as he mapped out his narrative, only to conclude by completely disavowing the idea of narratives altogether. He spoke about how the Vals hotel project featured in ‘M’ has changed the way Morphosis conceives of putting together future presentations. He touched on how the firm is approaching the Pershing Square redesign competition in downtown Los Angeles, and his steadfast commitment, going forward, to only take on the work he really wants to do. He detailed how any architect who is passionate about her work will invariably have to learn to manage anger, disappointment, and frustration. This abridged transcript of our conversation focuses on the concept and story behind the monograph, although we also briefly discuss how to remain optimistic in an incredibly tough profession (as well as Mayne's favorite Jim Carrey mantra), all in the context of putting together ‘M.’

In the introduction to your book, you write that your work is a critique of a culture that values the form of written language, as opposed to the language of form. Can you discuss that statement? It seems to define the entire book.

As a young person who was somewhat naive to the workings of the world in its political/social/cultural/normative conventions, I was very much living in my head. I don’t think I was particularly unusual, in that if you’re within one of the activities that’s part of the art world, by nature you’re probably a person who spends more time living in your head, and you live within the construction of the world as you’ve produced it, and you believe in that construction, and you operate by the conventions of that construction within your world. I was totally immersed in this notion of what architecture was or wasn't.

I think I was definitely connected to the conventions of my own knowledge of the world of artists, writers, poets, musicians, etc. and … I had nothing to do with it. I just showed up. Film was exploding, of course – Truffaut, Godard, Antonioni, Fellini, you name it. And of course music was being invented. It was rock’n’roll, and it was a completely new form of music. And with that came the altering of other forms. There were the Miles Davises and the Thelonoious Monks. Anyway. And of course there’s this explosion, especially at this end of the world in L.A., of the Irwins and the art scene. And so you are part of a normative world – it’s a world that’s open to invention, and definitely operates under its own rules. And your day-to-day life is hugely focused on your discipline, on your interest, meaning you’re not encumbered. I was married young, divorced young, and then spent the next 15 years on my own. It was conscious, for sure: I was aware that all my time was being used. I was totally immersed in this notion of what architecture was or wasn’t.

At this time I’m teaching, and I’m working with young people who are slightly more naive, and maybe not more optimistic, but have even less experience in the world at this other level...I’m in an environment which is still promoting a very utopian-ish, even if it’s focused on the dystopian, it’s still – you’re believing in some ability to change things and to somehow shape behavior. [...]

And then ten years later, you’re a little further along in your pragmatic world, meaning you’re making buildings and through the movement of ideas that are shown through drawings and the conceptual forms, you’re touching reality and you’re quite young with small projects, and now you’re dipping your feet into the real world, and it does have something to do with the You're invested in their perception of the world, reality, and that is in fact the basis of architecture financial world. You’re concerned that you’re paying people in your office as employees and you’re paying rent and there has to be some stability, and you’re starting to lose certain opportunities that you had prior to that. Now, just in terms of sheer energy, some of that energy is being used to deal with the day-to-day pragmatics. Skip another decade, and you now have a studio that’s been operational for the last decade, and you have 25 people, and you have health insurance, you have some stability, you’re taking responsibility for people’s lives, and the clients are bringing larger projects, and there’s no choice. You’re invested in their perception of the world, reality, and that is in fact the basis of architecture. Architecture is a social art form. [...]

You’re finding alignments between this world in your head, and this other world that has demands on its terms. [...] It’s quite radically disconnected from your world. If you’re going to be very pure about it, this world has no knowledge at all about your world. It’s an absolutely insanely private, esoteric conversation that you can have with a couple dozen people in the world, and it would be Robert Irwin describing his three yellow lines on a yellow field. I’ve lectured with him years ago, he can spend an hour discussing your optical behavior for that yellow line on a yellow field. It’s a conversation that’s interesting to a couple dozen people. And that’s the reality.

And it’s becoming more obvious to me what I’ve taken for granted in my visual world, this highly subjective visual world, when I’m talking to people: spatially, visually, conceptually, visual language that you take for granted. Or as I’m teaching with students, it’s the line where you decide if people are heading for architecture. If they don’t have the inborn capabilities, the synaptic wiring, it’s like trying to say everybody’s going to be like Miles Davis: but if you don’t have the wiring, you ain’t gonna be Miles Davis! Nothing different. That would be a good example. Any art form, pushed to some level, operates in those forms. If you go to the extremes, you do reach Miles Davis, who is unable to talk to anybody. He’s so extreme. It’s an artform. It’s an incredibly, beautiful insane thing for a human being. You could say it’s the highest level of human achievement or capability of having that kind of uniqueness. That kind of inventiveness, that openness, which seems to be the singular character of the human being that separates us from all other living things.

'this is odd to tell you, because I'm about to start a lecture and talk to you, but if I had my choice, I would say nothing. As we're going through this, I'm becoming more and more aware of the difficulty. If you talk to people of my community, they would always tell you, everybody that’s known me for a long time, they’d say ‘Thom has struggled.’ That it was sometimes painful to watch me lecture because I’m struggling to find words to describe my work. In my 30s, when I just beginning, people would say, it’s so painful to watch him do this, because he’s attempting to make it clear. However, I was aware enough of it that I remember saying, ‘this is odd to tell you, because I’m about to start a lecture and talk to you, but if I had my choice, I would say nothing. Everything I have to say to you is in the work I’m going to show you. There’s nothing left. There’s nothing I can tell you.’ And it was clear to me, but I live in a world that operates through discourse and words and is much more articulate, within a traditional literary sense. So I had to do it, it was part of my academic world, and I got better at it. [...] But finally, the work, artistically, conceptually, there’s nothing to say. I’ve shown it to see the work. It would be no different than poetry. E.E. Cummings said if you can explain it, I wouldn’t have to write it!

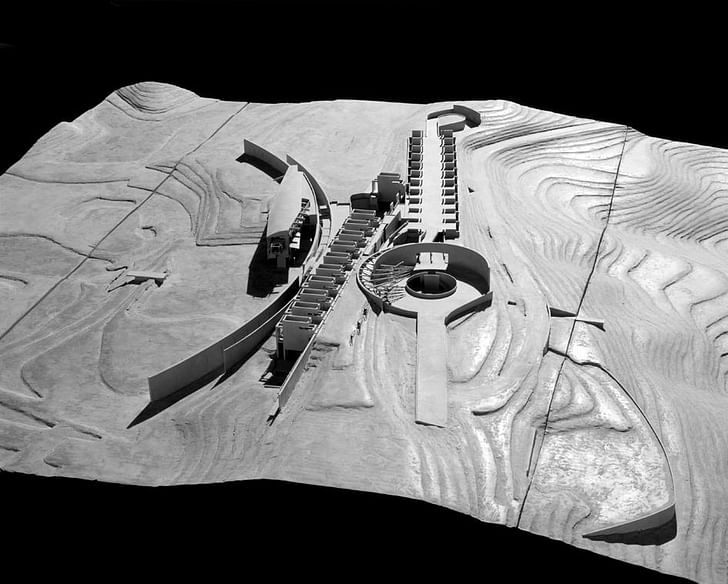

And so I’m looking at this piece behind me [gestures to a model of the Chiba Golf Club hanging on the wall behind us], and there’s nothing I can say, other than describing it in the most mundane terms, which I’ve learned to do. [...] In the book, I tried to do that. That answer your question? I’m 72 years old. I’m trying to make something that proves my commitment to the artform of architecture.

We’re doing now large buildings. I have two billion dollars worth of work for which I’m hugely responsible. [...] I’m self-conscious about my position in the art of architecture. I’m in a manic mood of continuing to prove myself within the artistic side of the discipline as I see the world, especially in the last twenty years, move radically to the right politically. It’s moved into this incredibly post-revolutionary position, and it’s absolutely affected the arts hugely; architecture, completely.

So again, going back to the book, we wrote the text a dozen times at least, shorter and shorter. It started out as a manuscript of 50 pages, and then decided forget it, we won’t even really talk about these buildings. We realized in a way that it was kind of accurate, that starting my fifth decade and looking at the work that’s a resolve of our research over four decades and I tried to explain the first, that we didn’t do much work, it was more thought, and the second decade I started doing a little bit of work, and then this stuff happened, the computer showed up, these things happened, I got it down to 12 pages, made the type large.

You put all of your projects in bold, to highlight them.

I re-read Kafka’s “The Trial.” It should have that kind of sparsity, where you’ve lived a lifetime in a page. That will be unbeatable of course, I’m looking at the world record holder in that territory! [...]I’m giving you the territory that surrounds the work, I'm self-conscious about my position in the art of architecture these are the things I was looking at, this is what I was thinking about at the time, in very, very short order. And I’ve really stripped down to the minimum. [...] We purposefully showed drawings that are very architectural, and very purposeful. And we wanted something visually luscious and kind of rich and accessible, for sure. We’re not really worried about what people will or won’t like; I don’t concern myself with that kind of thing. For myself, we had conversations with certain people who had done it, and we pulled out color palettes and looked at things, looked at Gauguin, the color richness, redid the whole thing so all the colors so the book belongs to one idea, the book is a singular thing. They come out of many photographers, many shoots, many drawings, many projects, we had to go through and put everything together so it feels singular. I think we did that. And then it’s for your eyes. And you’re either interested or you’re not interested. And that’s something I can’t control.

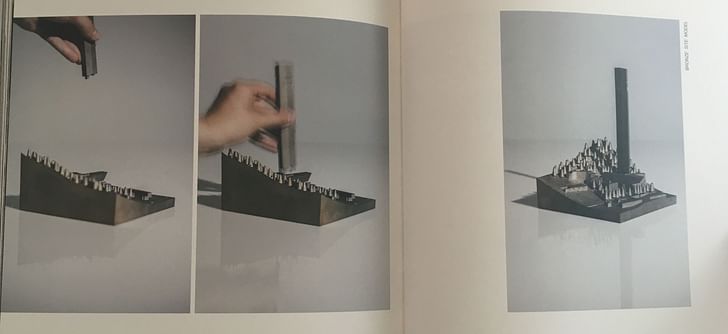

I love the way you laid it out in terms of starting with the placement of each project with the aerial view of the urban context. I did have one very specific question though about the visual language in the book. You feature the Vals Hotel, and you have a series of three photos of the bronze site model. The series shows a hand putting the tower into the site model. In the middle picture, you’ve purposefully chosen to show a blurred hand and tower to signify motion. I was intrigued by this. In the book, you write about how the Vals Hotel is confronting the sublime: that’s your concept behind it. So why did you include a photo that is blurred?

I guess throughout the book there were fragments of the action of drawing and making. Because we’ve recently been using more and more photographs of the hand of the maker or the supposed maker who is involved in that. [...] We recognized that the models and the drawings in of themselves had their own autonomy. They weren’t the building, they were the thing itself. They were connected to the building, they had aspects of the building, but they were not the building. There’s pieces of that; it’s residual thinking. We're going to show less and less building and more about the human emotional context of that building

The last photograph in the book is the woman figure in the pool. That was strategical, actually. It was tactical. The Vals was the last project that we literally added to the book having just won the competition, so maybe it’s also the least thought out in terms of the images. [...] The last image was purposefully a.) very architectural, and b.) it was about the sensibility of the project, and not the project itself, and it’s going to be something we’re going to continue now in another direction. We’re going to show less and less building and more about the human emotional context of that building, because we wanted a very sensual – it was a very interesting client. [pauses] It was a competition. One of the last statements of the function of the hotel, one of the key aspects of this hotel is that it had to be a place where people had really great sex.

That’s what came across in the photos!

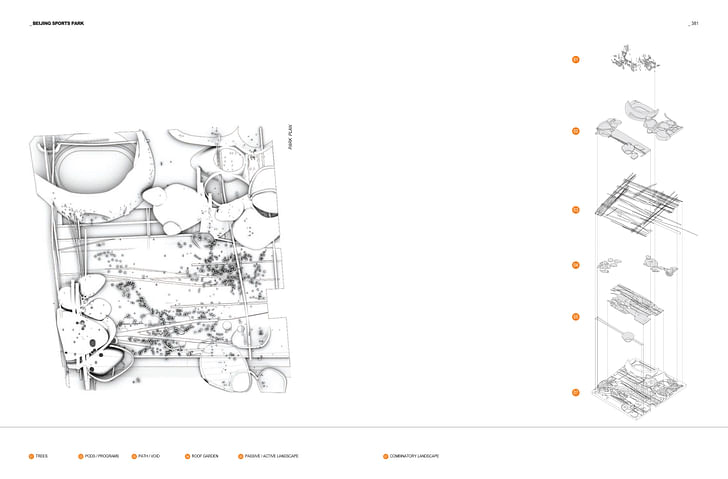

I stopped, ran into the whole studio, I said I’ve been working for four decades, never have I gotten a program where it said, this is a project that we want to have really good sex in! It was hilarious. [...] And I have these worlds now, and I have this urban planning urban world, and it’s strategical work, not the aesthetics, and I have my architecture, and then I draw and I have my artwork. There are these three areas I move around in. We're putting together a narrative, a strategy of the park, it is not about the design of the park, that's secondary The strategical thing has had a huge influence on the architecture. And it’s allowing us to place the architecture within broader political, economic, and cultural terms. It’s helped us rethink – we’re part of the Pershing Square competition right now – and we’re putting together a narrative, a strategy of the park, it is not about the design of the park, that’s secondary. It’s about strategically building a park downtown L.A. in the 21st century. This could be a performative park in a completely different direction. And the design’s way down the line. We’re saying its secondary.

[...] So this strategical work affected the Vals hotel. [...] When people go to hotels, it’s a fantasy. They want to go away. The other model is nature. When you go to Hawaii or a beautiful site, now the architecture is somewhat secondary, and you’re searching out 19th century nature in its unfettered form. It’s Arcadian nature. It became clearer and clearer to me that the design project takes an architect in a completely different direction, and that’s probably why architects don’t do hotels, it’s another groove, and that’s probably another story.

Anyway that was hugely useful to us when we did this scheme, it was this goofy scheme and we’re at a place now that I want to do work that I’m proud of. Never have I gotten a program where it said, this is a project that we want to have really good sex in! We don’t worry about the pragmatics. If it’s a nice idea we’ll go for it, we’ll win some and lose some, but I’m not going to deal with a normative world, ‘this is what it’s supposed to look like.’ Even more so, I’m back to where I was when I as a kid. The point being, the last photograph? The client would tell you we won the competition. We got it. He understood that we understood. We showed another photo of a woman in bed. And actually, I had a photo of two people in the shower, a man and a woman, you could see their feet, and somebody in my office said, it didn’t even occur to me, ‘Thom, that’s a menage-a-trios.” I was looking at the composition: I liked the two feet on the bed, I liked the woman behind the shower, it didn’t even occur to me. I said, “Leave it.” [...] The point being is that what that did to us and what’s fascinating with our work right now, is that it’s re-engaged me with the world in the exact opposite way I was talking to you about at the beginning of my autonomy with no connection, and we’re trying to find out, because we’re now at a place because of the scale of the work, that I have no choice: I’m either engaging in their world or I don’t work.

[...] It’s a tough business world, a tough pragmatic world. It’s an extreme one that has absolutely no idea what you’re doing – although, that’s not true. It’s the mood I’m in. I’ve had contractors come – when we did Cooper Union, we had this kind of middle space that was quite intriguing. I remember meeting the guy who headed that up, that’s handmade with his whole family, and that was wonderful. It’s one of the best experiences of my life when people do that. And he was proud of it, because he made a sculpture. He wasn’t a contractor making a building that he could care less about: he made something that somehow he could attach to without any education, without any knowledge of art. It is observable if you make it. But now we go back to, “You’ve got to get enough of it made to show to the public.” It’s a chicken and egg thing. Our experience is that it’s really hard to move through the world, but once you do it, you find that many more people support it, and in fact find it meaningful.

Once you’re able to articulate it, and people can understand it, then yes: people respond to it.

You have to get through the economic cycles and somehow make it happen.

We were discussing the difficulty of working with developers, and the frustration of conveying your interior world to a largely uncomprehending exterior world. With these frustrations, how do you remain in the profession? You mentioned Lebbeus Woods earlier. He went into the world of drawing where one is not necessarily going to have to fight as vigorously.

He and I were good friends, and he used to tease me. He’d joke with me that he was aware that he didn’t have another part of him that dealt with this world that we’re talking about, this world of building. He’d joke, he’d say, ‘Thom, for whatever reason, you were built for this.’ [...] You develop techniques. Sometimes I rant in the car before a meeting, and I go into this full-on emotional rant, and just unload myself. I don’t ever get – people don’t see me get angry. I’m not that kind of person. But I’ve kicked in a wall. [...] But mostly, there’s no choice. There’s times you’re very angry. I’ve gone through some tough times in my life.

My mid-forties, I had a tough patch. My wife helped me through. And I was just angry. And it was for a couple of years. It was affecting my teaching, it was developing a certain kind of negativity. I wasn’t a very optimistic person. And you have to be optimistic to be in this profession. If you didn’t have it, wrong profession. [...] A lot of students that are waffling and that are talented, my advice to them is why don’t you talk to other architects, but they have to be over 40. If you’ve behaved and done what society wants, you’re done for. Because they were educated the same way we were educated, and we are all somewhat idealistic, and we know what the potential of art is, of our craft is. Now you realize that you didn’t make it, and you’re deeply angry in a way that is unsolvable. [...] If you've behaved and done what society wants, you're done for

My wife came out of the fashion industry. She was teasing me. We’ve been together for 34 years. It’s a tough business, the fashion industry. Then she ran the office for twenty years, left about five years ago. After working for a while, she said, ‘Thom, I can’t believe it. You’re in the toughest work known to mankind.’ And it is. Because of that, it has to be a love affair. [...] It’s hard, even at this point in my life, not to get angry. [...] But, um, it’s easier for me now than at 45. At 45, I was just beyond angry. And now I’m quite well. I knew what I was getting into; I’ve gotta think it out. It’s not that you can control your feelings; you’re still gonna be really pissed off. But I have perspective: I’m getting this done, and I’ve got that. What’s the choice? It is not for everybody. [Laughs]

Fewer people care about the aesthetics. That goes back to the book. So the book is done for us. I’m not concerned whether anybody’s interested or not; if they’re interested, they’ll find it. That’s how we go through life. The phone rings. We don’t market. Our job is to produce work that is somehow compelling and if it’s compelling to us there’s a chance that just a few of the seven billion people – we only need .0001 percent of the people – we only need five or six jobs a year! The odds are in our favor. There’s that famous line of Jim Carrey when he was asking a girl for a date in that really dumb film, ‘Dumb and Dumber:’

[From the film]

J: What are my chances?

W: Not good.

J: Like, one out of a hundred?

W: I’d say more like one out of a million.

J: So you’re telling me there’s a chance! Yeah!

And he says, I’ve still got a chance! That totally cracked me up! That became, for a couple of years, that became the symbol of our practice of architecture, because yes, I get it completely, I would have said the same thing! A million to one, that’s way better than I would have thought!

This has been fun.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

7 Comments

Morphosis is great but that Val's Tower is a horrid program from the start.... and every project has an unwritten assumption of sex to begin with.

Thom LOVES to talk.

His nonstop prattle is a better explanation for any alienation he might be feeling than "singular genius"

why not just publish a 7000 word long read? how often do you get a thom mayne dishing out the story of how he got up and survived? Never. Thats literally the one story you never get. Whos gonna complain about the length, even if he rambles? its the internet, i can come back later.

and this cat didnt even get a link to his (not so hot) website: http://archinect.com/features/article/149368552/working-out-of-the-box-jader-almeida

and how come no one has published a picture of the other side of this: http://archinect.com/news/article/149934108/architect-behind-matrera-castle-restoration-argues-criticism-is-prejudiced#CommentsAnchor but we all get to hear how terrible it is?

sorry. im out of kudos today, gave them away elsewhere. reads like bites and gaps.

is there a 7000 word read? i heard once that Thom slept in his car to pay his employees.....and the one time our class toured his office and we met him he rambled right into why at the time he was into drag racing...... they say the fine line between genius and insanity is success, wish more people would listen to the insanity. bite and gaps it may be if you can not fill in the blanks, no? .....i thought this very representantive of the profession if you want to continue to create, and even more so in expressing the zillion layers of complexity that is involved......... he explained quite well why you do not get a lot of under 40 stars..... ...but no one ever really understands, like when your high school buddy or your business advisor wonder why you make such and such decisions and the only reaponse you can give is an angry mumble because explaining it would take too fucking long........met the facade guys for Cooper Union a while back, they said Thom was a very good architect to work with. he sat down with them and no ego worked through the problems and explained the design.......thanks for posting

All that angsting to get to work that is barely distinguishable from Bjarke Ingels'?

If there was a Nobel Prize for the person who best exemplifies the spirit of art - any / all art I vote for Thom Mayne. The Pritzker is not enough - too narrow - too focused on architecture alone. Tom embodies the spirit of all art - all music, frozen and otherwise. When he speaks he speaks of film, music, painting, writing, philosophy - the worlds surrounding/defining/creating architecture. Thom is a GREAT communicator in all languages surrounding architecture in his effort to explain-define-describe his buildings: forms and spaces, their intention, the dialectic comprising the thing and its context, the positive and the negative space, the yin and its yang, the career struggle and the career payoff. Thom is THE artist of our time who happens to be an architect. At 75 Thom is just getting warmed up (see: Wright, Kahn, Corbu, Gehry). Look for a deeper simplicity as his architecture leans into what he knows about words. Think U.S. Grant writing memos to his generals as cannonballs fly overhead - concision reigns. Thom weilds occam's razor inventing a language of the 21st Century.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.