Soft Baroque, the London-based design studio founded by Saša Štucin and Nicholas Gardner, has made pretty significant ripples in the design world for a practice just barely two years old. Their strange but visually-delightful furniture functions both online and offline, incorporates unwieldy materials like fireworks and water vapor, and treats history like a hunk of clay to be molded. They have an adept and playful way of involving conceptual elements in their work that makes you wonder how form and function alone ever seemed like sufficient ends for a design – or, at the very least, why your living room table is so boring.

With works exhibited in international design festivals and lauded exhibitions like “Pavillon De L’Esprit Nouveau: A 21st Century Show Home” at the Swiss Institute, Soft Baroque has begun to showcase their distinct design vision to a larger audience. I got in touch with the duo to find out what makes them tick – and how they see both the world of design, and the world in which design lives, changing around them.

I was thinking we could begin with a bit of biography. What are your backgrounds? When did you start working together as Soft Baroque?

We met at the Royal College of Art, where we got our MA degrees, but it was only afterwards that we started working together.

We come from different backgrounds. Nicholas from traditional furniture making and Saša from visual art, which works really well for us. Nicholas is the hands and Saša is the eyes, but we share the same body that thinks alike. We bring different skills to the table, yet we are interested in the same ideas – although Saša often draws things that wouldn’t hold together in real life.

How would you describe the design ethos of Soft Baroque?

We are keen to blur the boundaries between acceptable furniture typologies and conceptual representative objects. Our studio is sort of a contradiction: we are interested in what “modern luxury” should feel like, expanding functions as well as the story of an object into an inflated version of reality without abandoning a sense of consumer logic and pragmatism – what we consider “future practical”.We often respond to the space between our digital lives and physical objects.

We often respond to the space between our digital lives and physical objects. The outcome is often sculptural rather than a fully resolved commercial product. [Our design process] is a method of experimenting and questioning the possibilities in this junction. Although we do like to see our objects being used, which distinguishes them from being pure sculptures.

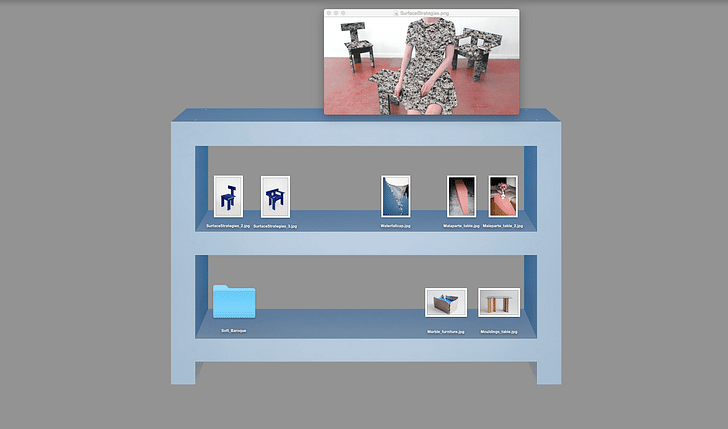

Going off this, your work exhibits a particular sensitivity to living in a “post internet” context, or an era marked by the dissolution of any clear or set boundary between online and offline. For example, your “Desktop Shelf” for the Swiss Institute exhibit was designed to function as both a physical shelf and as a computer desktop organizer. In what ways does the internet, and digital culture more broadly, demand new approaches to design?

Much has already been said about skeuomorphism in relation to the interface of programs. They are ornamental references to functional items in the real world. Designers are standing up to [this design concept], proclaiming dishonesty and a functional disconnection. Indefinite abilities to refresh emails, news, updates, tweets etc. on the screen makes the distinct line between the on and off-screen blurry.

With younger generations the link between conventional mediums and technology is becoming more common than it ever was before. Technology has become a necessity not only when it comes to design, but for everyday life. It has become faster, cheaper and a more efficient way of resolving things. The internet has changed society like the industrial revolution did in [the] past and we designers should respond to this.

“New Surface Strategies” also involves digital re-presentation as a fundamental element in its design. Can you describe this series?

Planks of a uniform dimension were flocked chroma blue to make a pre-finished material, which was then cut and assembled together. By keying out the blue color with the help of software, the surface of the furniture got digitally substituted for another surface input. A live camera feed displayed the chairs with altered surface textures that existed indifferently from the physical material.

The “New Surface Strategies” installation was a distillation of a few ideas. Firstly, it came from the goal of digitizing the decoration of furniture objects. The bits that were in surplus to necessity could be digitized as a method of liberating it from the constraints of material properties. It is a hypothetical idea.Update a surface of the furniture like you would update your desktop background.

Our system works the same way as any TV weather forecast using a green-screen background. We used the same logic for a two-dimensional background with three-dimensional objects and digitally re-appropriated surfaces. We used old technology that is now accessible to the webcam generation. Update a surface of the furniture like you would update your desktop background.

We think that materials used in the field of contemporary design are becoming less utilitarian and are used for their symbolic status, even expensive, high quality substances. Pattern, ornament or decoration has been replaced with just material. I guess it is a vestige of modernism; materials and forms were more true to their industrial/natural heritage. We feel that [materiality] has spilled over from functional solution into something that is still purely symbolic, like the carved decorations on a Victorian sideboard.

I’m interested, with “New Surface Strategies” and other works, in the way you balance function and concept. The plank construction of that series, for example, explicitly references precedents like Gerrit Rietveld and Enzo Mari. How do you balance these two imperatives, concept and function? Does one outweigh the other?

Yes – both Mari and Rietveld proposed a way of unifying construction techniques based upon prefabricated materials in order to make their work accessible and economical. We made a system using planks in the same sprit, but with a surface treatment that the digital software could respond to. We turned our focus to pre-finished material, that is, in this case, flocked planks of a uniform dimensions to be cut and assembled together. We created a system to build your own furniture, using standardized planks we produce.You need to know the pre-definitions of things if you want to challenge them.

More broadly, how does design history figure into your practice? I’m thinking of pieces like the “Malaparte” coffee table or even “Mouldings”, which employs traditional architectural moldings in quite a unique way.

Design history plays a big role in our practice. You need to know the pre-definitions of things if you want to challenge them. “Malaparte” and “Mouldings” are two projects that address architecture and its heritage in two different ways.

Saša has always been a fan of “good old architecture” and she often gets obsessed with buildings. For her, they work as icons. She got obsessed with the famous Villa Malaparte in Italy, which appeared in the movie Le Mépris (1963) by Jean-Luc Godard, and she wanted to turn it into furniture. So we ended up miniaturizing this piece of modern architecture and making it into coffee table.

While the coffee table “Malaparte” is about dislocating architecture from an urban reality that got privatized into one’s living room, “Mouldings” explores the misuse of a modern raw material, and the cultural and sculptural conclusions that can be made from exploring this phenomenon, with the aim of imparting a new form on these materials. “Mouldings” works with snippets of architectural design discourse using timber profiles found at any DIY superstore. These derivatives of classic architectural taste are subject to a rather banal series of cultural developments.

Tell me a bit about your “Fireworks Chair”. I love the material contrast of wood and fire, and the idea of detourning such a ubiquitous and utilitarian object for such an exuberant function.

We had the idea of trying to make the most entertaining chair around. Increasingly design is becoming a source of entertainment rather than an object in service. This was the most direct and exaggerated representation of this, a temporary and destructive act that leaves you a little empty after it’s finished. As for materials, we wanted to make a generic object, in a way to see how little designing we can do. It is all about the entertainment.Objects and buildings are at the mercy of people to support their existence.

The “Fireworks Chair” seems to share a certain absurdist humor with pieces like “Waterfall Cap”. Can you describe that piece? How do humor and absurdism figure into your practice?

We think it’s more about creating new links between elements that usually wouldn’t be paired. We believe it’s important to re-think these connections, which actually often don’t make any sense, but because they haven’t been around for so long, we don’t question them anymore. We read them as natural occurrences, even though they are part of standardization that was “designed” at a certain time for certain needs. Objects and buildings are at the mercy of people to support their existence. They function in the way we wish to inhabit or use them. If atmospheric conditions or our needs change, a process of evolution must take place.

“Waterfall Cap” replicates the natural occurrence of a waterfall and turns it into a personal waterfall. By turning on a switch, you can experience the view from behind a waterfall while you work, transport, eat or relax. Very common, everyday elements like water and a cap, when put together as one, form a new experience.

Even though the connections we design often seem humorous and absurd, we want to contribute to a debate about how objects can change the way we experience the world and, conversely, how objects change when we change the way we wish to experience the world.

Can you tell me a bit more about your motivation in employing environmental phenomena, like waterfalls or mist in the case of “Lenticularis”, as materials in your work?

“Lenticularis” and “Waterfall Cap” were two of our first collaborations. We were very interested in transcending the natural and creating new sensory experiences by doing so. These objects also relate to our research at the Royal College of Art. Nicholas was writing his dissertation about artificial indoor islands in Northeast Germany in a work titled “You get a nice feeling of heat surrounding you; Pleasure and Truth: A description of Tropical Islands”, while Saša was exploring the senses with a focus on smell while writing “Design After Design: Smell and Archetypes”.

“Lenticularis” and “Waterfall Cap” are inspired by our collective human desire to replicate natural phenomena for pleasure or relaxation: wave pools, indoor tropical islands and snow resorts in the desert. The “Lenticularis” replicates a natural climatic occurrence that almost disables the mirror’s traditional function, and in doing so produces a new sensory experience. A water particle cloud partly obscures the reflection and perfumes the air with the addition of a scent. It is a tool to dress the body in scent and enhance the interior smell landscape. The mirror becomes a pseudo-functional screen, a zen portal that reinforces a dream-like sense of a new private reality. Like an open fire, it is mesmerizing and hypnotic.

I love your “Marble furniture series”. The rough textures contrast beautifully with the resin top. Can you tell me about this series?

“Corporate Marble” is a series of marble pieces constructed from resin and glass fibre. Resin composites are generally reserved for hi-performance components, but here they are bonded to shattered stone slabs: a weighty, fragile material of luxurious corporate lobbies and buffed floors. The new composite is an exaggerated form of existing contemporary product solutions, revealing inconsistencies and false functional rationalities in modern consumer taste.

Traditionally a craftsman’s practice would be in proximity to the raw material used to fabricate objects. In the same fashion, we produce work in the context of the metropolitan environment: processed materials manufactured for domestic interiors and the DIY market are manipulated to unconventional ends. New raw materials, mined from internet shopping sites and DIY superstores, are converted into objects that still possess an echo of their intended use.We produce work in the context of the metropolitan environment

Where have you shown your pieces and how have they been received?

In the past, we’ve showed our pieces at major Design Festivals in Milan, New York, Stockholm, London and Dubai, as well as institutions like the V&A museum and Christie’s. Recently we exhibited “Desktop Furniture” at the Swiss Institute [in New York] as part of the Annual Architecture and Design Series titled “Pavillon De L’Esprit Nouveau: A 21st Century Show Home”.

We received a lot of interest in our work from the Swiss Institute exhibition. The show itself was great because not many galleries are doing more progressive design projects like this. Felix Burrichter, the curator of this show, created an extreme living environment that was simultaneously a viable living preposition and a cautionary tale.

Thanks so much for talking with me. Just one last question: what are you working on now?

We are developing new ideas, working on a proposal for large commission and a show that will hopefully happen later this year in Denmark. We are also taking part in a group exhibition at Apalazzo Gallery called “SUR” in Brescia this February. The show will present designers that are experimenting with new materials and searching for new conceptual and aesthetic values.

We we would also like to expand some of the exiting series like “New Surface Strategies” and “Desktop Furniture” into larger installations.

Looking for more places to sit? Find more "future practical" (and present practical) pieces here, part of Archinect's special February theme, Furniture.

And don't forget to send us your own furniture musings, interviews, critiques, designs, projects and investigations for review to be featured on our site. The open call ends February 21, 2016 – more details here.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.