Founded at a time when Frank Lloyd Wright was floundering financially, Taliesin’s blend of education and site-bound intimacy has created a custom domesticity. As the site for the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, Taliesin combines both passion and white-knuckled acumen, teaching its student inhabitants to thrive with scarce resources and a generous community.

The notion of interdependence isn’t one that most people take to naturally. Perhaps as a result, the live/work Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin (initially built as a private home for and by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1911 in Wisconsin, followed by a second campus in Arizona in 1937), has never been a particularly harmonious place. Beset by murder, fire, and the constant threat of financial ruin, Taliesin’s emphasis on creating strong communal bonds is as much about teaching aspiring architects how to work together as it was a kind of perennial income stream to Frank Lloyd Wright himself.

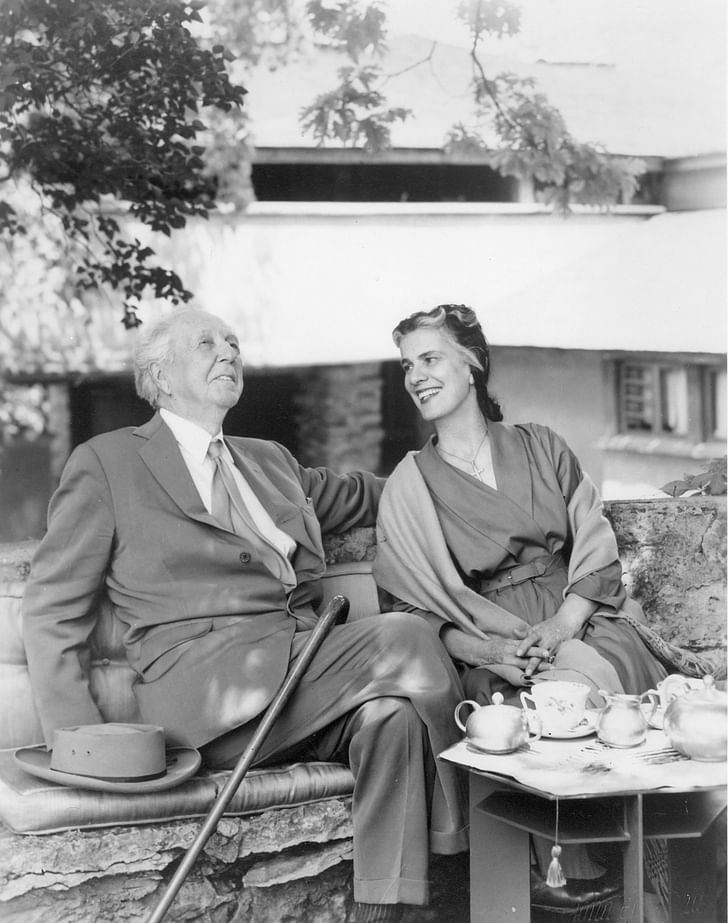

professional collaboration and domestic interdependence have undergirded the institution for over 100 yearsThe architect, whose genius haltingly distilled into cash, designed a domestic sphere that would support him creatively while also funding his work. Although Wright has been dead for over half a century, the Prairie Style aesthetic and shared living spaces of the school’s two active campuses work in tandem (students are in Arizona during the spring/fall term, and Wisconsin for the summer) to create a singular, workable domesticity. What’s fascinating about this model of domesticity is how ably it adapts to the challenges of designing in the highly competitive 21st century: specifically, by fostering an architectural culture that values both idiosyncratic vision and communal execution.

At both the east and west live/work campuses of Taliesin, professional collaboration and domestic interdependence have undergirded the institution for over 100 years, regardless of one’s rank or expectations in the outside world. Former 20th century fellow Cornelia Brierly recalls that when a visiting marquis refused to serve his Taliesin companions at dinner, Frank Lloyd Wright took him aside, asked him what his problem was, and adjusted the man’s attitude. “Eventually, our prince learned to work shoulder to shoulder with everyone,” Brierly writes in Tales of Taliesin: A Memoir of Fellowship.

Seventy years later, this expectation of shared duties and no-holds-barred intimacy still remains, if perhaps in a less meddling form. As part of their traditional thesis work, students are expected to design and build a desert shelter where they will live—while the students are now encouraged to use sites and materials from already-built shelters, it's an undertaking which requires substantial coordination and interdependence. It’s this basic formula that in 2015 fueled the design and building of two student shelters out in Taliesin West’s plot of Arizona desert by students Daniel Chapman, Mark-Thomas Cordova, Jaime Inostroza, Dylan Kessler, Pablo Moncayo, Natasha Vemulkonda, and Pierre Verbruggen. The The students not only had to learn about each other’s strengths and weaknesses, but how to use those qualities to accomplish a tangible goal.students collaboratively built the shelters with $2,000 for supplies from local warehouses and whatever materials they could scrounge up in the desert. Although they could rely on the knowledge of their instructor David Tapias if needed, the students made design choices as a group. After a chilly night spent in sleeping bags, they decided to build two structures instead of several smaller independent ones to make the most of their resources.

The somewhat austere restrictions of the project, both financially and within the context of making use of found materials, required that each choice be considered and approved collectively. The hands-on engagement of the project also removed any lingering abstract notions; this was not an exercise on paper in an air-conditioned classroom, but a sweaty, splinter-ridden design/build construction site. Most importantly, it was as much about engaging in interpersonal intimacy as it was about refining one’s design chops. The students not only had to learn about each other’s strengths and weaknesses, but how to use those qualities to accomplish a tangible goal.

But what is the longevity of this form of domesticity? While the students of Taliesin often reunite and keep in touch throughout their lives, there are others who have lived, studied, worked, and even given birth while on the grounds. Floyd and Caroline Hamblen, employees for Taliesin East who lived for nine years within a three-bedroom apartment onsite that was originally built for draftsmen, raised five boys within its 1,200 square feet. Former Taliesin graduate Floyd mentored new apprentices, while Caroline headed the this was not an exercise on paper in an air-conditioned classroom, but a sweaty, splinter-ridden design/build construction site.Taliesin Arts and Culture Program. In a nod to the institution’s interdependent roots, the apartment formed a part of their compensation. Although their digs were technically off-limits to Taliesin tourists, the curious would sometimes wander off the beaten path and up to the Hamblen’s windows for a look inside. According to an article in the Wisconsin State Journal, the boys grew up as integral members of the larger community, helping out during large family-style dinners and in the community garden.

Much has been written about the lack of work/life balance in the 21st century, but Taliesin provides an intriguing model for architects looking to dissolve boundaries between the two entirely, supported by an empathetic community. While its small scope and bucolic locations make it less relatable for denizens of dense urbanity, its blend of intimate collaboration in pursuit of professional goals could offer a doable, if intense, solution to creating a holistic working life for practitioners and students alike. Whether one views it as a productive cult or a groundbreaking collaboration, its brand of domesticity is not forgettable.

This is perhaps best summarized by the presentation statement of the Taliesin student shelter team, which noted that “constructing can be very tiring, sometimes very frustrating. Under the Sonoran sun, it can be nerve breaking... When you glimpse a colleague’s happy face of discovery, the joy of seeing things that you thought of actually work out, the most daring, intriguing, wild ideas running smoothly, the light coming out of these faces gives you the greatest feeling possible. Don’t expect architects who haven’t experienced that to understand it.”

This piece is part of our special editorial theme for July 2016, Domesticity. Check out related content here.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.