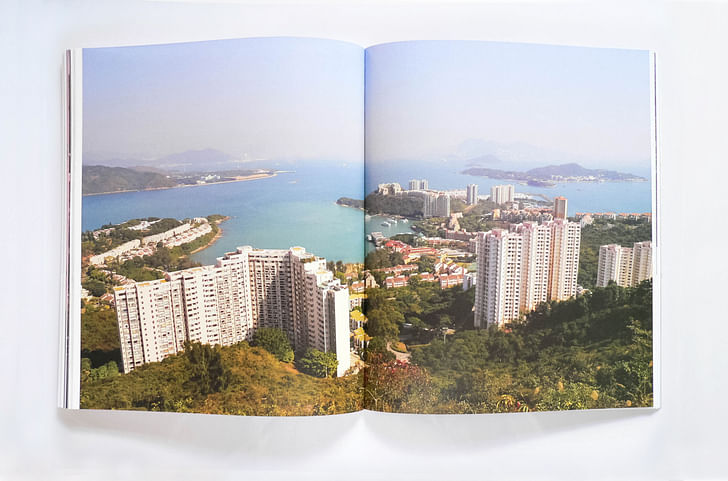

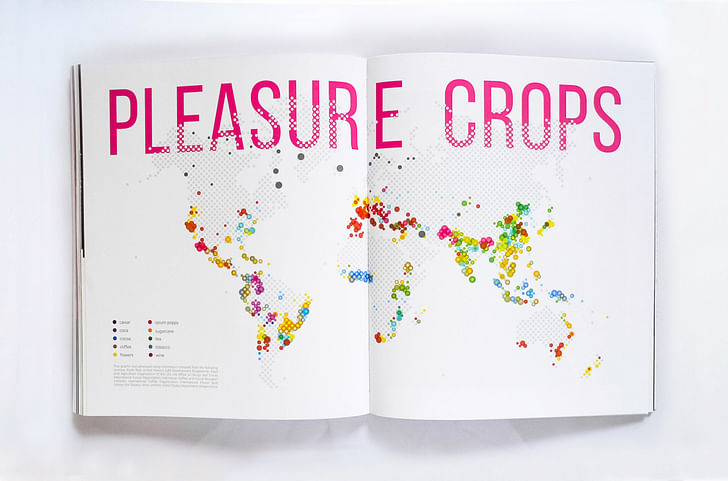

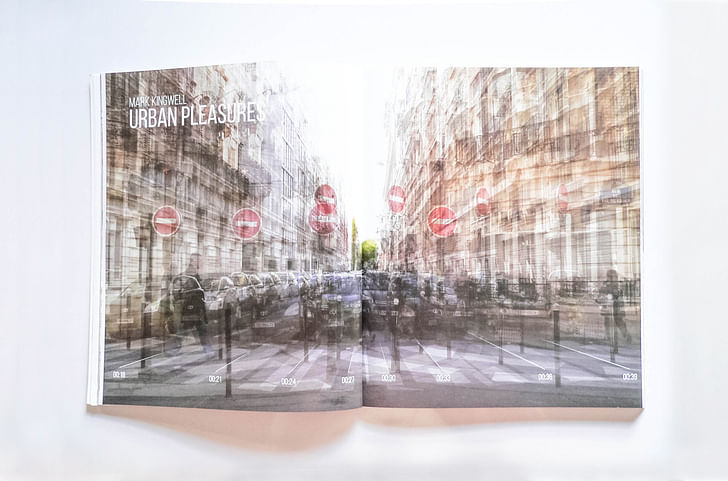

In an era marked by ecological crisis, the figure of the landscape architect can assume an austere, if not downright sanctimonious, stance. Like some contemporary prophet, the landscape architect calls for repentance, moderation, and preparation – a voice in the wilderness of our apparently excessive time. Yet the discipline’s origins are far less pious, as is made clear in “Pleasure,” the newest issue of LA+, produced by the Landscape Architecture Department at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design. Revisiting arcadias of past and present – from the gardens of Ancient Rome to the resort-styled Discovery Bay development in Hong Kong – the issue considers the complex relationship between landscape architecture and pleasure.

“Pleasure” includes a well-curated range of essays, interviews, critical histories, psychogeographies and more. Innocent diversions and more licentious proclivities are considered, providing a framework to analyze the conflictual moralizing tendencies of the discipline. In line with the journal’s stated interdisciplinary intentions, “Pleasure” draws connections to philosophy, neuroscience, art, and other fields.

Our featured excerpt for Screen/Print is “Why So Serious, Landscape Architects?” by Phoebe Lickwar, the Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Arkansas' Fay Jones School of Architecture, and Thomas Oles, Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at the Edinburgh College of Art, University of Edinburgh. The polemical essay underscores some of the larger conceptual concerns of the "Pleasure" issue, calling for practitioners to “descend from our decorous heights back whence we came.”

“Why So Serious, Landscape Architects?”

By Phoebe Lickwar and Thomas Oles

Open any recent copy of Landscape Architecture Magazine and you come face to face with a world going to hell. Tales of crisis and calamity abound. The September 2014 issue, for example, confronts the reader with the “agony” [1] of drought in California, the “trauma” [2] of Mexico’s drug war, and the “fear” [3] of rails-to-trails projects in the United States. Even the public park (Chicago’s Lurie Garden is nice but “does have its flaws” [4]) offers little respite from the general gloom. It would seem that there is a great deal to worry about. But it is not the individual chords of the lament that strike one—we have heard those many times before—it is the backbeat of moral injunction that runs beneath them. Don’t just sit there, landscape architect! Rise up and seize the challenge! There is no time to waste in the “quest to save” [5] endangered species, eroding coastlines! Our efforts may pale beside the problem, but professional deontology demands that we make them nonetheless. Like a doctor giving a risky drug to a dying man, we are bound by oath to do something for patient Earth. After all, we just might find “salvation in a grain of sand.” [6] More than any other design professionals we fancy ourselves lone visionaries, speakers of truth in a world of lies, guides on the path toward deliverance.

This oath to save has produced its own distinct form of psychic discomfort in the contemporary practice of landscape architecture. It is different from the pain endured by creative artists, which derives from the terror of making something—anything at all—out of nothing. It is also different from the torment of architectural education, which prepares students for the ignominy of a working life marked by long hours and low pay. No, the pain of the landscape architect is something else entirely. Ours is the pain of moral ardency, the anguish that derives from our fervent desire to redeem a fallen world. Like medieval flagellants, we do penance for the original sins of our species (agriculture, money, technology), shoulder guilt for the misdeeds of our predecessors. We groan under the burden to repair, reconnect, reclaim, restore, regenerate, and revitalize, adopting places lost, poisoned, abused, discarded, or forgotten. Visions of apocalypse bring us a strange and often poorly concealed Schadenfreude, confirming our sense of doom but promising growth in demand for our services. More than any other design professionals we fancy ourselves lone visionaries, speakers of truth in a world of lies, guides on the path toward deliverance. We matter (the incantation would go, were it ever sung aloud) not merely because we see and solve ‘problems,’ but because we are right. More even than specialized knowledge or technical skill, this rightness is the good we hawk in the global marketplace, where the sign on our tent reads: VIRTUE FOR SALE.

This is serious business, to be sure. But are we not allowed some fun, too? Does our pain for the world, our knowledge of apocalypses to come require us to forego pleasure altogether? If the things that we design are to delight as well as redeem, surely we ourselves should be able to delight in the process of making them, and to infect others with this same delight? But we are fun! comes the objection. It is just that pleasure must be useful, the means toward the morally legitimate end of persuading the (well-meaning but benighted) public to attend to those things that really matter: sea-level rise, species extinction, drought and desertification, peak oil, the obesity epidemic, the anomie and isolation of smartphones, and celebrity pornography. There is far too much to be done amid this catalogue of ills for mere pleasure, especially when such pleasure might implicate us in the very pathologies we purport to cure. We are prone to lament the disappearance of landscapes of play (yet another modern ill), but only for children. For the rest of us, banished as we are from that garden forever, landscapes must educate, enlighten, edify, redeem. So there we landscape architects stand, perched on a wobbly crate in the town square, delivering our lugubrious sermon to an indifferent world as it rushes past to the Apple Store.If we think disavowal of pleasure will raise our prestige and expand our influence, we would do well to think again.

But if we think disavowal of pleasure will raise our prestige and expand our influence, we would do well to think again. As any principled but failed politician will confirm, pained sanctimony risks undermining the very ideals in whose name it is adopted. For one thing, it raises suspicion among a citizenry grown weary, and wary, of moral crusaders – whatever their professed aims. For another, it undermines creativity. Romantic myths of the artist aside, pain generally depletes rather than enhances the capacity to wonder and delight at the world. It saps our confidence, silences our intuition, and reduces our willingness to risk and innovate. All this makes it harder, not easier, to give the mind that license, that play necessary for creative practice. Worst of all, though, is what pain does for our relationships with other people. The body in pain, Elaine Scarry famously noted, is a shrunken body, loosed from the social world, a dweller in a distant land with which lines of communication are damaged or broken. It is a body unable to connect, to engage in that imaginative exercise, essential for all social life, called empathy. [7]

All this might be fine for a large and prestigious profession, secure in its domain and immune to the vagaries of public opinion. But it is thin ice indeed for a discipline with a relatively small number of members whose utility remains a complete mystery to most people. [8] Do we really not see the danger at our feet? We are on our way to becoming a buzz-kill profession, the reticent but secretly envious wannabe at the party who looks down on the frippery and is left off the list for next time. We are on our way to becoming a buzz-kill profession, the reticent but secretly envious wannabe at the party who looks down on the frippery and is left off the list for next time.

What is to be done? There is no single answer, of course, but we might begin by stopping our present headlong march toward positivist shores we will never reach. Let us instead turn around while there is still time and aim for the rock right behind our backs: the passion to dream and make environments of sensory bliss that drew many of us to landscape architecture in the first place. However we may bristle at the thought, it is this—not ‘evidence-based design,’ not ‘landscape performance,’ and certainly not moral uplift—that society continues to expect of us. Our value does not lie in our capacity to create landscapes that forestall or avert global catastrophe, or to restore what has been lost. It is hard, even heartbreaking to bear, but what is lost is almost surely lost forever, and far more is poised to follow soon. Our value lies instead in our capacity to imagine and create places that elicit joy, pleasure, passion, and wonder despite this. For it is the small, ultimately aimless pleasures these places offer—a child’s laugh, the splash of water, the scent of dry grass at dusk—that make life still worth living. If this discipline has any moral core, if we stand for anything at all, surely it is this.

Landscape architecture is about well-lived lives, lives that unfold in the company of others, human and nonhuman, amid air and light and warmth, free from sickness and ugliness and alienation and want. Whatever pain we may feel apprehending a world where the rights to these basic things are denied to so many, we must continue to take joy and pleasure in them – not because we must forget, but simply because others take this joy in conditions far less propitious than our own.Landscape architecture is about well-lived lives, lives that unfold in the company of others, human and nonhuman, amid air and light and warmth, free from sickness and ugliness and alienation and want. And part of this joy, this pleasure despite it all, is the joy of being silly, unseemly, obsessive, excessive, illogical, gauche, wasteful, and childish. It is being able to embrace with equal abandon the amusement park and the park, the boardwalk at Coney Island and the boardwalk through the wetland, all the while insisting on the legitimacy of both. If this discipline is ever to amount to anything more than a footnote to apocalypse, we must start to wear our pleasure—in materials, shapes, colors, sounds, smells, memories, the fellowship of friends, and the voices of strangers—on our sleeves. We must start to shout, and show by our own example, how pleasure is the most serious, the most radical thing in this broken but still miraculous world. Before we do any of this, though, we must cast off the yoke of moral rectitude once and for all. We must descend from our decorous heights back whence we came. Down there, in the marvelous realm of the senses, in the mire and muck of life—improbable, pointless, glorious, irreplaceable life—we will rediscover not only ourselves but our profession.

(Note: Endnotes to this piece can be found in the image gallery below.)

Key members for "Pleasure" include:

Other contributors to "Pleasure" include:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured LA+'s second issue, "Pleasure."

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Thanks for featuring this journal.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.