During the 2015 London Design Festival, Groves Natcheva Architects exhibited a short film they'd made, entitled Black Ice. Written by Adriana Natcheva's brother and shot entirely in his house – which the architects had designed, and located across the balcony from where Groves Natcheva is based – the film is a powerful study in dark, brooding suspense. Indeed, so much was made of the “psychotic” plot of Black Ice by certain elements of the design press, that perhaps the real essence of the film was missed.

Was this just an architecture practice dabbling in “Tales of the Unexpected”-style filmmaking? Was Black Ice an advert? Or was this something more unexpected: are Groves Natcheva part of a larger movement to bring the process of residential architecture to life?My instinct was to reach out to theatre and drama and film to show it to people so they can feel the architecture, without judging it as a piece of art in an abstract way.

Visiting Adriana Natcheva and Murray Groves in their Kensington studio, across the courtyard from the house that staged Black Ice, we launch straight into the whys and wherefores of the film's reception.

"We hope that it will open an interesting discussion as to where architecture is at; how it's presented. It hasn't happened yet," says Natcheva, somewhat ruefully. "It’s a question of opening the debate up into the creativity of an architect and the objects architects are trying to achieve. My instinct was to reach out to theatre and drama and film to show it to people so they can feel the architecture, without judging it as a piece of art in an abstract way."

At a very base level is Black Ice an advert? "We are not producing content and then attaching our name at the end of it," says Natcheva. "We're not selling that particular house – if anything, we are selling a way of thinking."

What is this “way of thinking”? The writer of Black Ice, Parashkev Nachev – an eminent neurologist, artist, and furniture maker, who also happens to be Adriana Natcheva's brother – corrects the press and lays the story bare. "If you treat the visual as decoration, you will lose the plot," Nachev says. "The fact that this happens to so many who view Black Ice with 'design' glasses on illustrates our cardinal point."

The eye has insane dynamic range, far greater than any camera, yet we normally insist on flattening the visual with bright, uniform lighting, as if living were some kind of forensic audit.Does the Stage Set Itself?

Is Black Ice calling for a more poetic stance in the depiction of what architecture stands for?

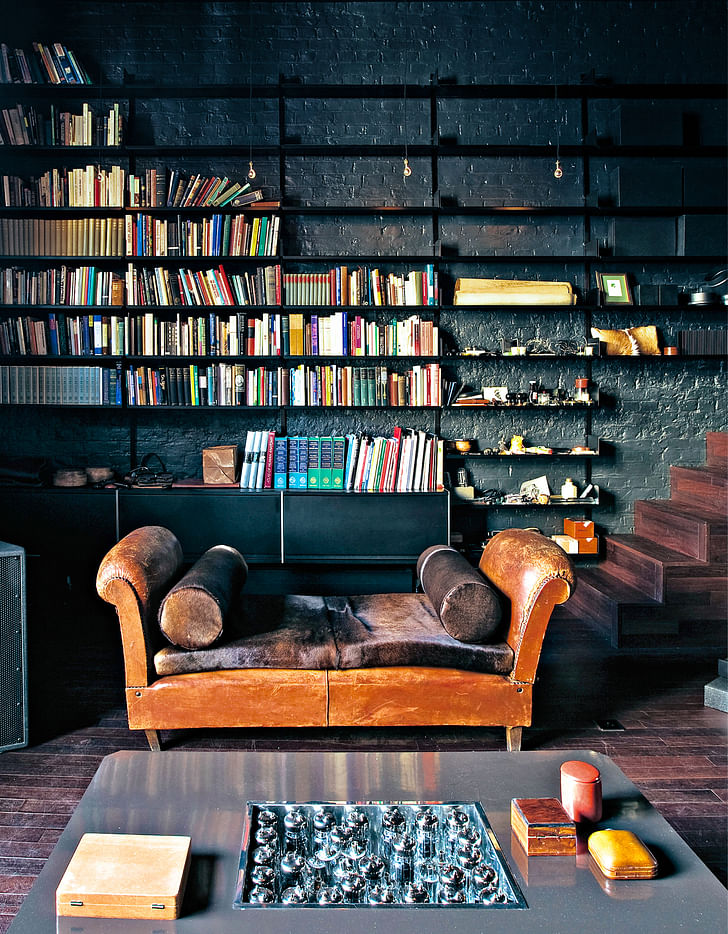

"Adriana was the architect of my home," explains Nachev, "but since it is a home rather than an architectural showroom, the result is a fusion of my content and her form, rather like a play is the fusion of someone's script and another's direction. It is also a conveniently dramatic space, for it is designed to be like a stage, shrouded in darkness – its features visible only where and when specifically illuminated. The eye has insane dynamic range, far greater than any camera, yet we normally insist on flattening the visual with bright, uniform lighting, as if living were some kind of forensic audit. Few of the objects in the space are off-the-shelf, fabricated: they are handmade, mostly by me, to be lived with more than to be looked at. So the space itself is a criticism of the flatness and sterility of conventional architectural representation."

Black Ice cinematographer, Nicholas Nazari, sheds some light on the relationship the script had with the space. "The script's narrative revolves around the elaborate vengeance that our main character sets up in a flat that her husband used for his lover. Our main character's anger and vicious resolve fit perfectly in the high contrast of the flat's natural lighting by day as well as the hundred flickering reflections that the cast iron stove spreads around itself at night. Her desire to explore this unknown and surprising space, this unknown and surprising side of her husband, as repulsed as she might be by it, drives her to walk around, touch objects and open panels. This gives us, the camera, a perfect excuse Public buildings become more like sculptures, to be contemplated rather than inhabited.to have the audience focus on architectural features without being expository about it." Nachev agrees, "Adriana wanted to draw attention to an odd aspect of contemporary architecture: that its public representation commonly ignores precisely what distinguishes it from mere sculpture – the life it is built to enclose."

Does this representational distortion matter? "It wouldn't matter if it didn't propagate into the architecture itself," explains Nachev, "but, of course, it does, especially now that a digital image of a building might have a far larger audience than the thing itself."

Is Nachev suggesting that contemporary culture leans too much on sterile digital appearance? "Public buildings become more like sculptures, to be contemplated rather than inhabited. Private buildings become more like chain hotels, to be stayed at rather than lived in." He continued, "It is not a reactionary point – on the contrary, it is a point about innovation being too limited to a very narrow dimension: that of a flat, sterile, catalogue appearance. And since architecture, in turn, shapes life, the consequences ramify a long way."

The Staged Door

In theatre terms, “architecture touching life” is no more apparent than in the immersive theatre companies led by Punch Drunk, Theatre Souk and Bush Bazaar, whose pop-up mentality has now spread beyond performance and into production spaces, harnessed by an umbrella organisation called Theatre Delicatessen.

The antithesis of sterile and catalogue, Theatre Delicatessen currently resides in a disused building that, until seven years ago, was home to The Guardian and Observer newspapers. Utilising vacant spaces around London (for short periods, and with the blessing of developers) as temporary rehearsal studios, workshops, offices, and venues for young creatives, Theatre Delicatessen pays a peppercorn rent to the landlords in return for the cache of an “artsy vibe” and the security of guard dog duties from the thespians.

But there is more than just cultural commerce and shrewd tenancy at work here: increasingly the company is looking to work with the building to assist in the narrative, and, rather like in the case of Groves Natcheva, they are looking to further dialogue between architectural they are looking to further dialogue between architectural practice and theatrical performancepractice and theatrical performance. The company now has several architectural practices working within the space alongside theatre companies.

The building itself is largely empty on the day I visit, and preparations are being made to vacate at the end of January 2016. Nestled among props and costumes on the second floor is architect Orla O'Kane of OOK Studio. O'Kane was the first architect to join the group, followed since by three other practices in the building. For O'Kane, it's more than just desk space: actively participating in working with the building for the benefit of all, O'Kane has become an unofficial architect in residence.

Relationship to Residential

"Fundamentally, it's about working within an existing building," explains O'Kane. "At OOK Studio we mainly do refurbishment projects. We do a lot of work with grade two listed buildings, and we work primarily residential. Whether you are transforming it for the brief of developer or client or the demands of a theatre production, the process can be the same."

What does O'Kane make of what Groves Natcheva are doing? "What's really interesting when it comes to the Black Ice film, is the parallel [with] us, in our interest in the idea that there is a certain performance to setting. Arguably film locations are anywhere, but I don't think it's about that." O'Kane thought out loud, "It's weird, it's not very apparent to most people. The creative process that goes into residential architecture has its part to play."

Groves Natcheva also work primarily in the residential sector. Could their work help unlock how architects relate to residential spaces?

As a profession, we probably don't do enough of documenting the intimate process and relationship between architect and client"As a profession, we probably don't do enough of documenting the intimate process and relationship between architect and client," says O'Kane. "No matter what you are working on, you're asking them, 'tell me how you live?' This can be unexpected for clients, it's the same with developers – there can be an initial resistance, but once you go through that, suddenly you are quite close."

How does this closeness manifest itself? "You end up feeling like you own it," says O'Kane. "There is a huge emotional investment by the architect, you own whatever is in your head until you hand it over to the client. There's also a slight breakup process, and it can be really interesting because you do feel like you own something. When the client pushes back and says, 'No I want this to be different,' it can be a very personal thing to navigate, and then you realise it's not yours."

Front of Home

Built in 2009, Zog House, In Queens Park, North West London is now home to developer and owner of Solidspace Gus Zogolovitch. Zogolovitch was the project manager for Zog House, and Groves Natcheva designed it. The house is to be the environment for the next film produced by Groves Natcheva.

What made Zogolovitch want to lend his home to the project? "I thought it was a great idea to use architecture in a way that is not just seen and to be lived in, but also potentially as a backdrop to other things," says Zogolovitch. "I really like the fact that they've made a house a vehicle for a narrative: a story that plays out within an interesting architectural space."

Zog House has been featured heavily in the press for its design and is a “character actor” in its own right, having been on TV adverts. So why is this so different from just allowing yet another film crew in?

"I think it's great that it’s architects doing it," explained Zogolovitch. "It's different too if it were simply someone coming to shoot a movie in the house; it would have no relevance. But Groves Natcheva is creating an ongoing narrative and a connection between how it was designed on paper, what it was for, but also this kind of ability to transform itself into something else, that's the exciting thing. To me, the house has a legacy of its own in a different way, as a home and as a backdrop."the house has a legacy of its own in a different way, as a home and as a backdrop

Whether architect or artist, it's logical to view a facade as a backdrop, every room as a stage and public space as an arena for spectacle, all crying out for dialogue. What of the architect’s role in working towards relating process and emotion through design? Theatre and architecture are well-documented relatives, and the profession is versatile, often leaning towards product and manufacturing and, as this year's Turner Prize espouses, Art.

"Architects have always worked in different disciplines, but I do think we are slow as a profession," said O'Kane carefully. "We haven't done as much as other creative industries to 'own' under-used or unused landscapes and buildings in the same way as other disciplines have. Until recently, I don't think we've exploited the natural skills we process. Now there are groups like Assemble and a generation of architects who are doing more interesting work in that way."

Speaking to Roland Smith, Co-Artistic Director of Theatre Delicatessen, about the company’s relationship to O'Kane and architecture writ large, brings this response: "It is about the dialogue. We have learnt from Orla what is possible, how we can articulate and realise our ideas around our built environment. What can architects, in general, learn from us? To be honest, it's a balance between intervention, access and responding to the part of our role is to ask uncomfortable questions about society, and to make interventions, both playful and serious, into our wider environment.environment in which we work. Artists and theatre-makers are instinctively non-conformist. Many of us feel part of our role is to ask uncomfortable questions about society, and to make interventions, both playful and serious, into our wider environment. As ever, that perfectly describes the work of some architects."

How does Smith see the objectives of non-traditional theatre, design and art developing alongside architecture?

"Our initial work had a resonance with situationist thinking; we were deconstructing the alienating urban environment. By taking over buildings in the centre of the city, specifically large-scale commercial properties that tower over local communities, we were breathing life into, and opening up, guarded spaces to the community. There is a sense of reclamation, and stripping back the concrete and stone to revel in the stories that are revealed – as they said in the '60s, 'under the cobblestones, a [sic] beach'."

How does Smith see his particular type of enterprise expanding in the future?

"Increasingly, our role is consultative or guiding," says Smith, "a phrase we hear a lot now is ‘space activation'. Artists will be commissioned to create happenings or performances that draw people to a space, or help characterise the identity of a new, or future, development."

For Orla O'Kane, the aim to diversify into working with theatre spaces that mix performance, making and ideation is the way forward. For Groves Natcheva, it’s the exploration of empathy between architecture and filmmaking, and architecture’s foresight beyond surface value.

The role of the architect is not that of a neutral force, and a building is not an inanimate object. The artistry may come in communicating that fact.

Robert studied fine art and then worked in children's television as a sound designer before running an art gallery and having a lot of fun. After deciding that writing was the overruling influence he worked as a copywriter in viral advertising and worked behind the scenes for branding and design ...

3 Comments

Perhaps related, I just listened to the new architecture podcast A Lot You Got To Holler, first episode of which discusses the city of Chicago as portrayed in film.

Thank you Robert

Great piece on interdisciplinary potentialities between architecture/theatre/film/art/politics.

Interested readers should check out the book 'Architecture as a Performing Art'

http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/9781409442356

thank you for the information in this article and to the prior commentees! all of these resources are helpful to me as I search for an MArch program that considers theater performance within the design process.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.