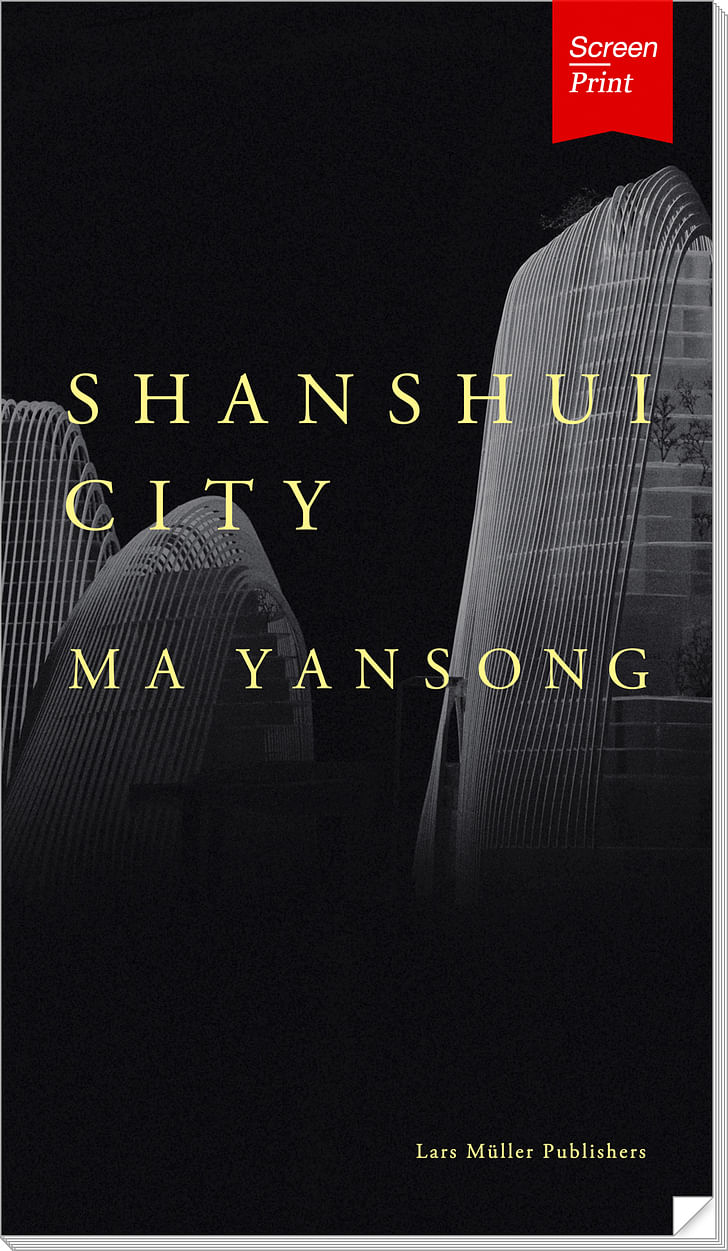

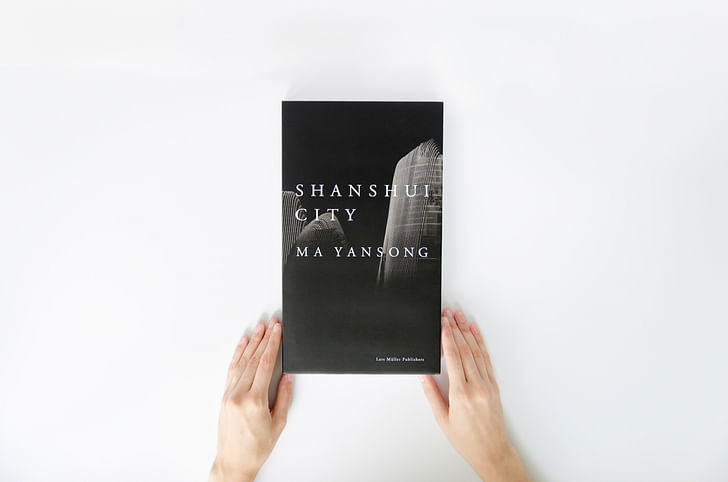

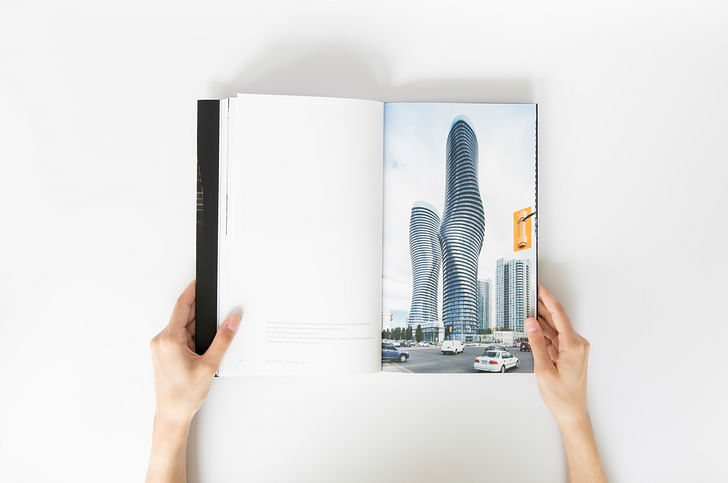

Part humanist wake-up call, part architecture manifesto, Ma Yansong’s Shanshui City emerges at a critical point for Chinese urbanism, as urban development accelerates to a breakneck speed of environmental damage and social concessions. Yansong draws stark lines between the Beijing he grew up in and the Beijing where he founded MAD Architects, pointing to the now-endangered urbanist details that made the city of his childhood livable and beautiful. Shanshui City is Yansong’s conceptual strategy for how architecture in Beijing, and elsewhere in the developing world, must retain what is so easily lost – they key being integration with nature.

Published ten years after MAD was founded, Shanshui City looks back on Yansong’s work, and sets the course for the firm’s future, which has certainly grown in influence (MAD recently opened a Los Angeles studio and is attached to the controversial Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Chicago). Featuring essays by Yansong, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Lorenza Baroncelli and Kenya Hara, the book lays out the firm’s philosophy of including nature as a means of retaining humanity throughout seemingly uncompromising urbanization – to build shelters of nature in concert with the city.

Our Screen/Print excerpt comes from Yansong himself, reflecting on how his childhood Beijing was able to balance an “epic” scale with subtleties and natural breathing-holes curated to a human scale, ensuring both awe and peace in the city’s form.

Old Beijing, My Childhood

My discussion of Shanshui is rooted in my feelings towards nature—not the “pure” nature found outside the city, but the pockets of nature within the city. It is this “urban nature” that allowed me to transcend day-to-day reality and find a sense of belonging in the city.

In retrospect, having these rolling hills and soothing bodies of water in such a large city was truly utopian.My childhood was spent in Beijing’s old, historic neighborhoods. In the center of every courtyard home was a large tree, and every part of our lives seemed to unfold underneath those trees. These courtyard trees were different from the trees that lined the street. People maintained an intimate lifelong dialogue with these trees; they were at the center of our family and community relationships. When I was younger, I would cross Jingshan Park and Beihai Park on my way home from school. In winter I would ice skate on the moat of the Forbidden City. In summer I learned to swim in the lakes of Shichahai and I caught fish off the Yinding Bridge. In retrospect, having these rolling hills and soothing bodies of water in such a large city was truly utopian.

Beijing is an epic city, constructed according to a grand order, yet replete with details that inspire our most subtle affections. As Lao She wrote, “The beauty of old Beijing lies in the gaps and voids between the buildings.” It is these voids that establish a holistic relationship The beauty of old Beijing lies in the gaps and voids between the buildings.between the buildings, people, and nature. Having an urban center complete with hills, bodies of water, and open land sets Beijing apart from any other metropolis in the world. The historical “Eight Great Sights of Yanjing,” which include Beihai Park, are a spiritual map of the city; its emotional calendar. These rich mythical landscapes are infused with the essence of ancient Chinese philosophy and aesthetics. They act as living canvases that can be experienced within the everyday lives of Beijing’s residents, and treasured in their memories. This remarkable example of visionary urban planning is the physical interpretation of an idyllic natural world nurtured in hearts of the Chinese people.

As a manifestation of the urban civilization of China’s agricultural era, Beijing avoided the impact of twentieth century industrialization. Instead, the city leapt directly into its role as the political and cultural center of socialist China. Over the past five decades, each new iconic work of architecture heralded a new direction in the city’s development. Unfortunately skyscrapers, cars, and gray skies have become Beijing’s new defining features. Today’s Beijing is a world apart from the old Beijing structured around order and nature. The original Today’s Beijing is a world apart from the old Beijing structured around order and nature.vision of the city has sadly been lost. The hutong (narrow lanes, or alleys) and courtyard homes are the lifeblood of old Beijing, but today they are reduced to quaint amusements in a theme park. The ordinary people who have lived there for generations eke by without showers or bathrooms in their homes, or are banished to the margins of the city by forced demolitions. In the face of this urban atrophy and functional disorder, I believe it is necessary to make changes that are centered around the everyday lives of hutong residents. It is not necessary to rebuild wide swathes of the city; rather, small-scale interventions can be employed to improve living conditions and revitalize the sense of community in what remains of these neighborhoods.

In 2006, I conceived a “micro-utopian” project, which I called Hutong Bubble. These small-scale modules are inserted into traditional courtyard homes and can be used as studies, bedrooms, bathrooms, or for any other purpose suitable for a small space. My hope is that these “bubbles” will have the vitality of newborn cells, endowing old architecture with new energy. In this way, the program aims to revitalize the entire community though the transformation of a few components. A few years later, we constructed the first “bubble” in an old neighborhood of Beijing. This addition consists of a bathroom and stairs leading to a rooftop terrace, housed within an organic skin reminiscent of a single-celled organism. Its curving metallic exterior reflects the courtyard’s ancient architecture, trees, and sky, thus blending into the environment. History, nature, and the future coexist within the dream-world reflections on the surfaces of these organic bodies.

History, nature, and the future coexist within the dream-world reflections on the surfaces of these organic bodies.Perhaps if we shift our attention away from large-scale, monumental architecture, we might be able to take a renewed interest in improving everyday living conditions in the city and rebuilding a community spirit. Maintaining the concept behind old Beijing’s urban structure does not necessarily entail replicating the old courtyard homes. Rather, within the high-density conditions that are the inevitable reality of future cities, we must consider how urban space can be shared and enjoyed, how to satisfy our yearning for harmonious interaction with nature, and how to preserve the integral spirit of older structures. All of these questions are related to our most fundamental human feelings, and determine whether residents can experience a sense of belonging within their urban environment.

Towards a Shanshui City: A New Order

People often ask me why I design so many skyscrapers when it is clear that I have such great affection for Beijing’s old courtyards. Can’t we just build our city of the future with courtyard architecture? It’s a question of density: with the vast scale of China’s population and the sheer speed of its growth, if every household had a courtyard home, Beijing would be consumed by courtyards from the mountains to the sea. Dense, consolidated urbanization is the only way China can protect its natural resources and farmlands. This is a precondition for all debates on future urban inhabitation.

Today’s megacities house populations of over ten million people. Due to the demands of greater efficiency and for the sake of the common good, these cities have given rise to a new form of society. I believe that people who live in dense urban areas have a special dignity. Megacities can facilitate the sharing of ideas and resources and provide a place Dense, consolidated urbanization is the only way China can protect its natural resources and farmlands. This is a precondition for all debates on future urban inhabitation.where different cultures and values can coexist in previously unknown ways. In our current context, unlike at any other time in history, developing low-density, high-quality residences must be viewed as being extravagant and wasteful.

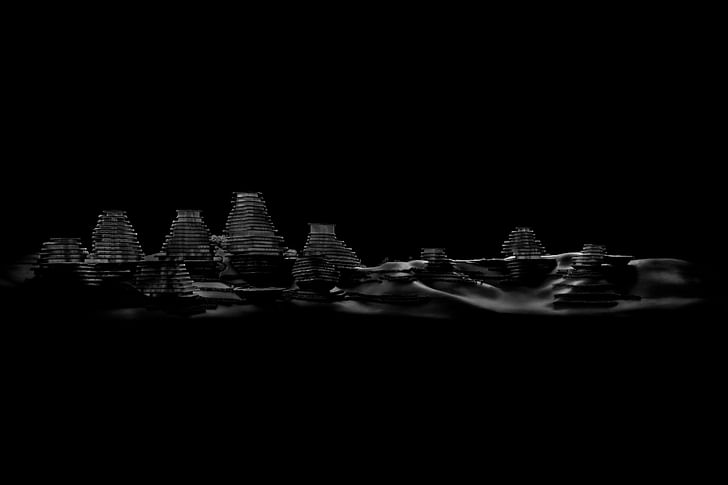

However, does a future without courtyard residences therefore imply an urban landscape devoid of greenery, and packed with oversized city blocks and skyscrapers? We cannot see the earth or trees. We cannot hear the birds. We lack communal spaces. Our cities do not support the most basic needs of the human spirit—to say nothing of their lack of character. Our discussion of Shanshui comes at a time when the modern city is facing an environmental crisis. As we probe the relationship between humanity and nature, our research ought to target problems facing large, high-density cities. Furthermore, this research should not only be limited to the cities of East Asia.

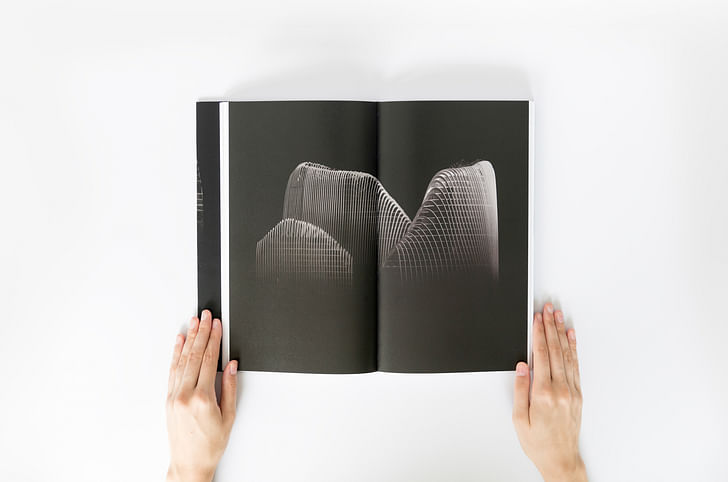

Shanshui is a worldview defined by the ancient Chinese understanding of nature. It is an ideal environment that exists in perpetuity within the psyche of the Chinese people, available to all. It embodies a certain understanding of nature, crystallized from cultural memories of interactions with the natural world. It is an emotional experience that connects a certain understanding of nature, crystallized from cultural memories of interactions with the natural worldus to our environment. It is not merely mountains, or rivers, or foliage, or any specific natural object. As the process of urbanization unfolds, so our longing for nature grows stronger. Thus, we begin to endow nature with social and cultural attributes.

The Shanshui City is a new mode of urban civilization centered on the relationship between humanity and nature. It requires the establishment of a new order in urban and residential planning which necessitates new priorities to define our urban ambitions. We cannot allow ourselves to be trapped in the infinite loop of technological development, with each new invention solving the problems created by the last. Instead, we must create a new holistic habitat for life and for the spirit. The facilities of the city should be defined with respect to how we would like to live and not vice versa. Residents should not be forced to accommodate a cold, abstract machine, lest our cities be overcome with antipathy and crisis. If we take the individual emotional response as primary, the result will be a humane and open city. While supporting the commons, the city should also reflect the great heights of artistic achievement and thought, just as the finest cities and gardens of ancient China were often the result of the collaboration of great thinkers and artists. In the realm of Shanshui City, art and thought are not mere luxuries; rather, they are directly integrated into everyday urban life.

Shanshui City is published by Lars Müller Publishers (July 25, 2015).

From the publisher:

“Shanshui” is an idealized Chinese worldview to seek and integrate spiritual refuge in nature among the everyday life of humanity. “Shanshui City” is not simply an eco-city, or a garden-city, nor does it imply modeling the city’s architecture on natural forms such as mountains. It represents humanity’s affinity for the natural world and our quest for inner fulfillment, as expressed in philosophies of the East.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured MAD's Shanshui City.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit an excerpt to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.