"I'm always looking at things and taking them at face value," said Mike Nesbit, a Los Angeles-based architect and artist, as he leaned over the table and grabbed an empty glass to use as illustration. He turned the glass over in his hands several times causing the reflection of an overhead light to splinter and reform with each rotation. “Surveying a found object,” he continued, “and trying to eliminate the predetermined meaning that I have in my hand.”

We’re seated at a table at Michael J’s, a Chinatown bar that seems locked in an eternal identity crisis. A recent makeover carved open the old building’s front facade, trimmed its edges in concrete, and injected tasteful, minimalist bathrooms. These qualities – alongside a well-curated beer selection – are likely what attract its typical crowd of young lawyers. But it’s also a place where you can become close friends with the bartender over a heaping pile of spaghetti and meatballs, and whose affable owner might just let you take over his parking lot if you need spillover space for a gallery opening. For this, it’s also become the unofficial watering hole for a burgeoning architect-cum-art scene in Los Angeles, which centers around Jai & Jai Gallery across the street and whose owners can often be found tucked in the bar’s back corner.

That night in October, the bar also served as the third vertex of a triangular preview of Nesbit’s newest exhibit, Swipe, a few days before its public unveiling. After talking for a few hours, Nesbit and I walked over to Jai & Jai Gallery, a small shotgun-style space currently housing a selection of his works on paper and concrete panels (full disclosure: the gallery hosted Archinect’s “Next Up” event a few months ago). Through repetition, you start to understand the effects of a thing that you do We continued from there down Spring St. until reaching the second space of the show: a vast, hypostyle hall still under construction, in which Nesbit had suspended a row of massive, wall-size concrete panels between each of the columns. Each work, in each space, comprises the same basic gesture: a thin layer of paint spread along the edge of a squeegee, brought down in a singular movement. The results, however, are far from homogenous.

“Through repetition, you start to understand the effects of a thing that you do,” Nesbit told me. “For the Swipe show, it was critical in the beginning to establish, let’s say, not a perfect swipe, but as close to a perfect swipe as possible. A swipe with no visible stroke." A dialectic of accident and artifice drives much of his work

Nesbit related swiping hundred of times in pursuit of this goal. As he was swiping, he began to identify aberrations that precluded its attainment: the slip of a foot caused a wiggling line, the stutter of the squeegee against the concrete panel produced a variegated pattern. Once identified (and then individually named) these aberrations, in turn, informed the development of new techniques. When Nesbit attempted to replicate one of these aberrant marks, they produced unexpected others.

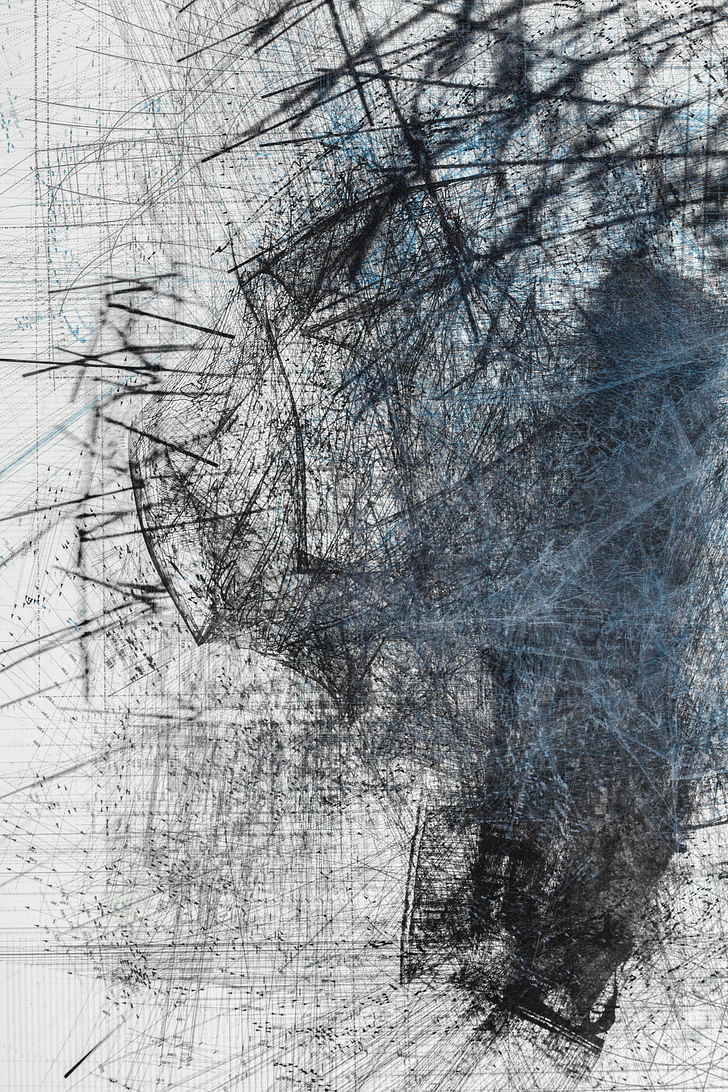

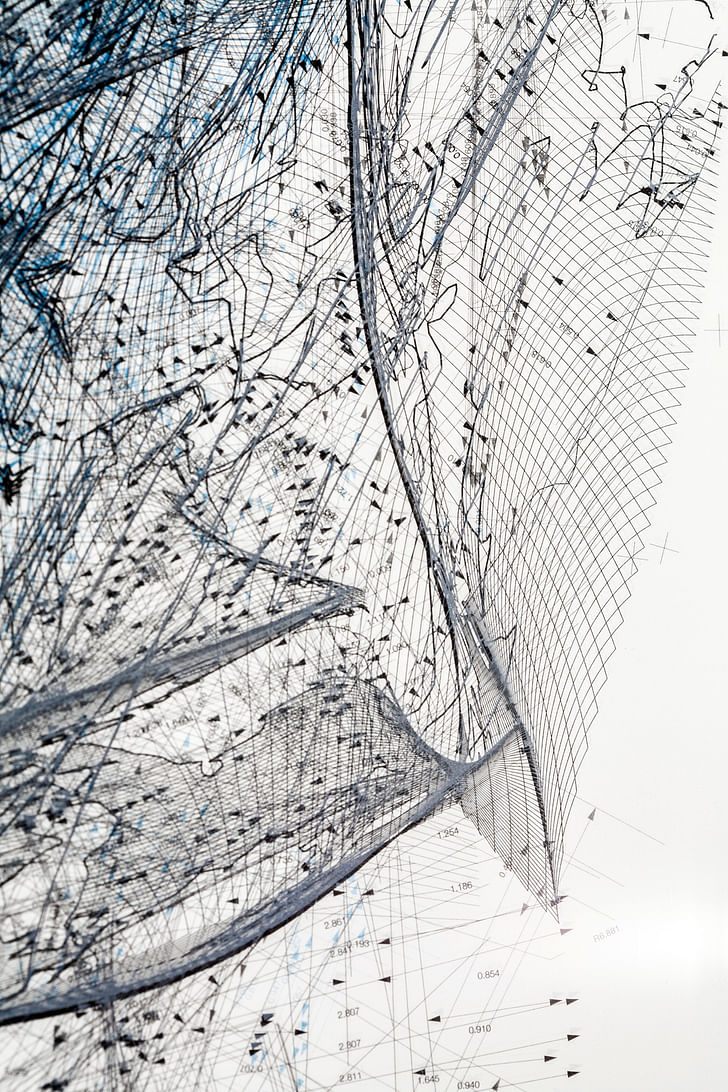

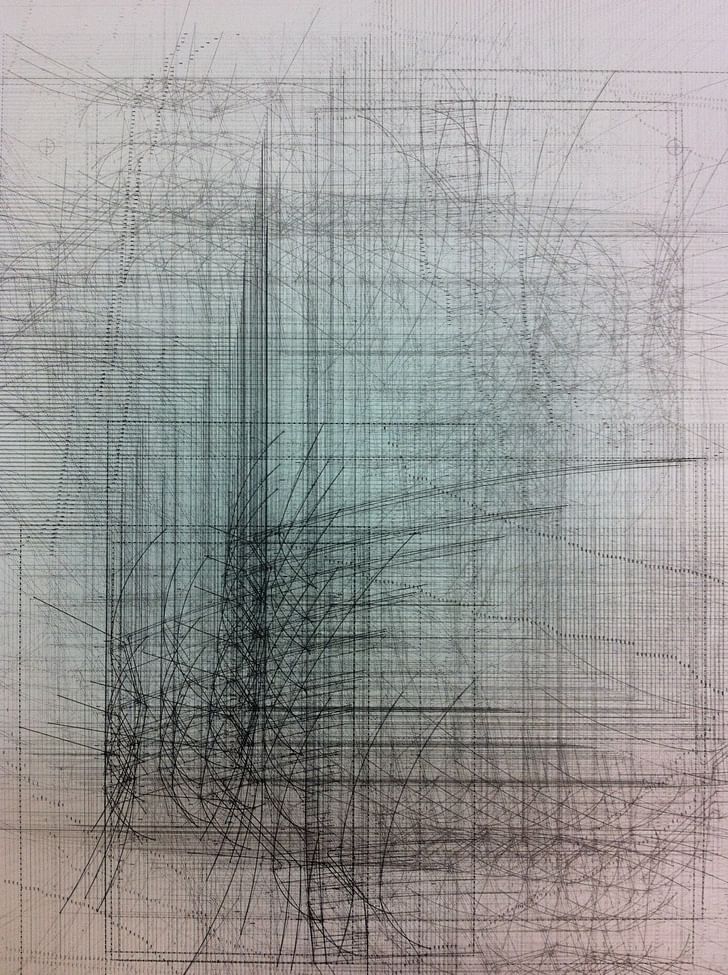

"I’m very interested in the relationship between the technique that's used and the representation that's produced and how that informs the technique, in turn, which is then reproduced in another representation,” he stated – in other words, a dialectic of accident and artifice drives much of his work. Consistently, his practice has included a consideration of patterned behavior. I've always steered away from biography, because I'm not nostalgicA previous series, dubbed “phlatness,” involved repeatedly annotating a 3D object until its capacity for signification lost out to an excess of information and the image was rendered abstract.

Part of his interest in the relationship between disciplined technique and unavoidable error stems from a background in sports. Nesbit played, for several years, as a centerfielder for the Seattle Mariners. Athleticism, at least on the professional level, is relatively rare in the architecture and arts circles Nesbit travels. As a result, this trivia tends to follow him around.

“I've always steered away from biography, because I'm not nostalgic,” he told me. “I’m more interested in what we're doing at hand, but I think I'm seeing that you can't divorce them from one another and, if anything, I can look back at baseball and see the kind of practice, the discipline, the doing-something-over-and-over-again repeatedly to develop a certain technique. I mean sitting in a cage and hitting a ball off a tee five hundred times, and just doing it repeatedly because you're trying to produce a perfect swing.” The best techniques are the techniques developed by the individual of what's comfortable for them

Nesbit made reference to the “changeup,” that type of pitch that starts as a fastball before slowing down, mid-air, to evade the swing of the bat. “Now, I'd think that the changeup happened because people got bored of the game and then someone said, ‘Oh I have to change it up,’ but who knows?” he mused. Could the changeup have been the result of a slip? An accidental jerk of the wrist? In any case, the efficacy of the pitch stems from its difference from the established norm of the technique. It’s unpredictability, in other words, is what makes it successful.

“There's always a tradition of what a technique should be and it's very apparent in sport – you have someone say, 'This is how you do it, this is how he did it, this is how that guy did it, this is what was successful' – and I think that as you get older you start to realize that's not necessarily true,” Nesbit said. “At the end of the day, the best techniques are the techniques developed by the individual of what's comfortable for them, which might completely go against the techniques that were taught before them.” For me, architecture pushes things that are irrational

This relates, as well, to Nesbit’s other world: architecture. After leaving the Mariners, Nesbit enrolled at SCI-Arc, where he graduated in 2012. For his thesis, he presented a series of abstract drawings. Thom Mayne was part of his review panel and invited Nesbit to come work for him at Morphosis after seeing his work. Since then, he’s become a project designer at the firm and has developed a relationship with the Pritzker Prize-winning architect. According to Nesbit, his work with Morphosis directly informs his artistic practice.

“For me, architecture pushes things that are irrational, that aren't necessarily practical,” Nesbit told me. He’s interested in the distinction between a structural engineer, for example, and an architect. While the former thinks strictly in terms of efficiency, an architect may be inclined to exaggerate, through scale or material, an element or object. By manipulating spatial norms, Nesbit believes the architect can invoke questions in the viewer or user, inducing considerations of their quotidian relationship with built space. Nesbit wants, perhaps more than anything, for his work to remain open to a diverse audience

At the same time, and like with his baseball metaphors, Nesbit underscores the delicate balance between playing by the rules and creative rebellion. The potential for an aberration to be perceived as such requires the continued presence of other, stable and normative conditions. Without this, the discourse loses its openness, its ability to be read. And Nesbit wants, perhaps more than anything, for his work to remain open to a diverse audience.

“It's a swipe. That's it,” he said flatly. Nesbit told me his mom can read it as well as an academic (assumedly implying his mom is neither an academic not particularly art-savvy). A kid thinking the colors look cool is as valid an interpretation as one steeped in critical theory. “I'm more interested in being very deliberate, this is what it is,” he said. “I think that, especially in academics, we've lost that clarity."

It's a swipe. That's it.

That being said, Nesbit also frequently referenced the art historical canon – his stated influences include Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhart, Mary Weatherford – and sometimes philosophy. His earlier body of work, “phlatness,” involved a consideration of ‘pataphysics, an absurdist pseudo-science developed by the 19th century French writer Alfred Jarry. There are many, often contradictory definitions of 'pataphysics, but a favorite is the “science of imaginary solutions.” If metaphysics seeks to understand a fundamental nature of reality beyond reality itself, ‘pataphysics deals with what is beyond metaphysics. Specifically, Nesbit’s own “phlatness” works derives from the related concept of a “pataphor,” or extended metaphor, invented by the writer Pablo Lopez. A pataphor can be thought of as something like a metaphor squared, in which the pataphor extends from a metaphor in the same manner that the metaphor extends away from reality.

With his “phlatness” works, Nesbit took an object – for example, a boot – and then annotated it so heavily that the original reference image, or 3D model, became an unrecognizable tangle of lines and numbers. He described the resulting works, which were silkscreened on paper, as “a critique of complexity for complexity’s sake” and “faux-parametric." Within the framework of the pataphor, this critique may read something like: parametric architecture is understood as an analytical metaphor for reality, Nesbit’s “phlatness” series serves as a pataphor for this metaphoric reality, creating out of it an absurd world of its own, thereby underscoring the non-reality of the previous metaphor. To put this more simply, the works are meant to trouble parametric architecture’s claim to realism. “A drawing of a drawing of a drawing to the point where it doesn't matter,” he explained.

As soon as we name it, then it's a thing In a way, the “swipes” extend from a self-referential dialogue with the “phlatness” works. With the “swipes,” an extremely simple gesture breeds complex and multiple works. With the “phlatness” series, an intensely complex solution is developed for a non-existent problem, leading to works so inundated with information they transform, paradoxically, into simple forms.

According to Nesbit, in both cases this involves a process of objectification, where the process itself turns into the object of study rather than the means towards a product. This is also why he names his artistic strategies – “phlatness,” “swipes,” “floods” – a strange sort of branding move that many artists might find unsavory, particularly when preceded by a hashtag, as often occurs when his work is reposted on social media. But Nesbit seemed genuinely surprised when I asked about the PR-associations implied by such a strategy. “As soon as we name it, then it's a thing,” he stated. “As soon as we're objectifying it, it becomes a thing to work with.”

But while he conceives the process as preeminent to the result, Nesbit also relayed a concern for the affective capacity of his works. In particular, he expressed hope that they would evoke sublimity, which, according to his understanding, comprises "something that is beyond the singular person and starts to provoke and produce questions of how, what, why.”

With Swipe, Nesbit’s main tactic seems to be scale. The massive concrete panels hanging in the larger space are by the far the most impressive of the double-show, to the point that they dominate and diminish the other pieces, in particular a series of adjacent swipes made directly on a brick wall. One can’t help but wonder about the fabrication of these behemoths, and the technicalities underlying their suspension. Nesbit told me that each weighs about 1,000 lbs.

Of course, this means Nesbit didn’t make them entirely alone, although they are custom-built. Rather, he gathered a sizeable throng of friends and collaborators to assist in their in situ creation, installation, and embellishment with pigment. That neither the ceiling collapsed nor any injuries occurred is a testament to the know-how and capabilities of his community, not to mention their willingness to help out a friend. Is the gallery Chinatown? Is the gallery Los Angeles?

For Nesbit, the fact that a community coalesced around the show stands as one of its most important qualities. He expressed to me his belief in the growing scene straddling the world of art and architecture that seems to orbit around him and his friends at Jai & Jai Gallery. “There’s this movement happening,” he said. Nesbit aims for his practice to extend and enliven that movement. In part, that directed his decision to simultaneously make use of the gallery space, the construction site, and vacant walls around the Downtown L.A. area.

“For the show, it was important to do something outside of the space, and extend the idea of the gallery, extend the idea of what is the gallery,” Nesbit relayed. “Is it Jai & Jai? Is the gallery Chinatown? Is the gallery Los Angeles? And I think that thinking – of what is the gallery, what is Jai & Jai gallery – is a very critical conversation.”

Extension – from aberration to technique, from reality to pataphor, from the gallery to the city – appears as the unifying movement in Nesbit’s practice. Similarly, his experience as a baseball player bleeds into his work as an architect, and, in turn, into his art.

The potential for Swipe to provoke conceptual or perceptual reflections for the viewer likewise depends on Nesbit’s ability to successfully translate his own interpretations into an affective experience; to extend his own thinking into the thoughts of others without recourse to more explicit rhetorical supports, such as explanatory text.You don't recognize the wall until it's swiped Just as how experiencing a postmodern building shouldn’t require familiarity with semiotic theory, understanding Nesbit’s conceptual strategies shouldn’t be a prerequisite for getting something out of Swipe.

“A brick wall that we would pass and think nothing about; you swipe it and all of a sudden it becomes somewhat provocative,” Nesbit said, describing the intentions of his new work. “You don't recognize the wall until it's swiped... you're so used to looking at a brick wall that you forget what it is.”

Swipe is on view from Saturday, November 14, 2015 – Saturday, January 2, 2016 at Jai & Jai Gallery, 648 North Spring Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 as well as the off-site location, 837 North Spring Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012.

For more information, visit Jai & Jai Gallery's website.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.