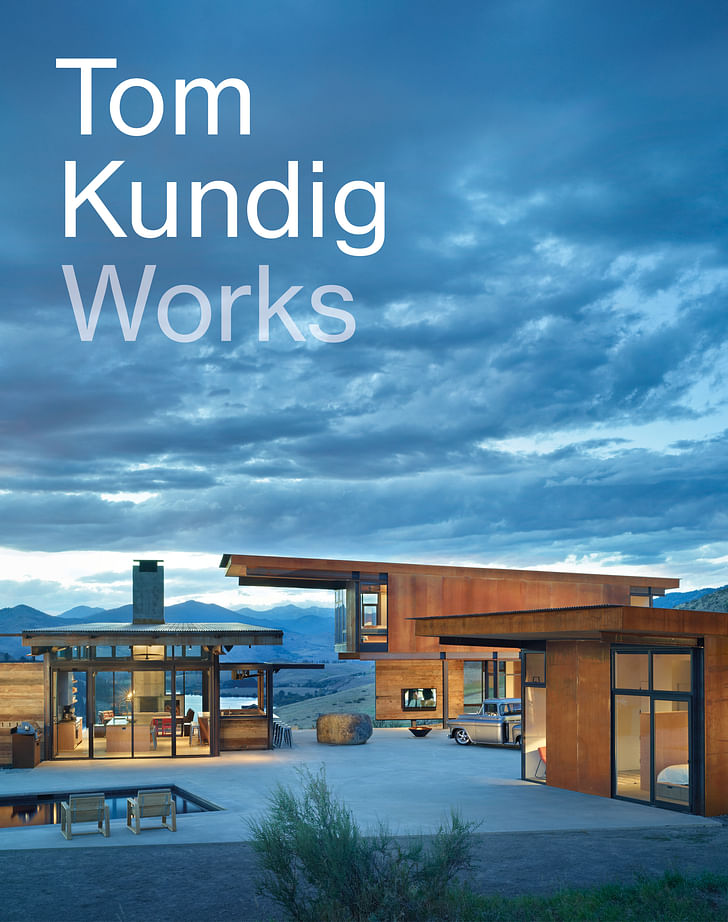

Tom Kundig has a few credits to his name: aside from a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, the Smithsonian’s 2008 National Design Award in Architecture Design, and eleven national AIA awards, his firm Olson Kundig has also twice been named one of Fast Company’s “Top Ten Most Innovative Companies in Architecture.” Now, the would-be geophysicist turned architect, known for his inventive blending of mechanics and aesthetics in private residences and public buildings alike, has a collection out by Princeton Architectural Press featuring his latest nine works, called Tom Kundig: Works.

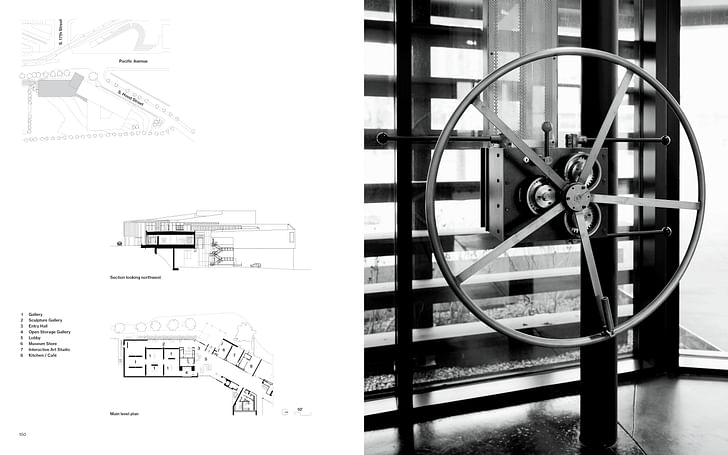

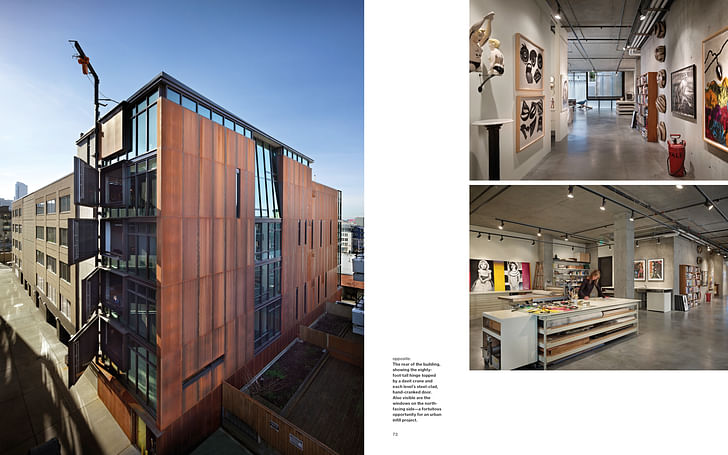

Tom Kundig grew up in the Pacific Northwest, and has subsequently made a career out of designing sophisticated single-family residences that embrace the rural landscapes in which they are sited (sometimes, not without controversy). Many of these residences incorporate “gizmos” – large-scale mechanical workings that not only open walls, doors, and skylights, but also set a distinctive aesthetic tone that emphasizes emotional tactility. Since joining and eventually becoming partial owner of Olson Kundig, Tom has benefitted from the developing a distinctive aesthetic tone that emphasizes emotional tactility.resources and strategies of the firm, branching out beyond houses to design the Tacoma Art Museum Haub Galleries, Charles Smith Wines in Washington state, and the Shinsegae International office tower in Seoul, Korea, among other projects.

a holistic and intimate portrait of his working processWorks incorporates the architect’s personal observations about his projects alongside conversations with frequent collaborators and clients (including thoughts from Olson Kundig's resident-gizmologist Phil Turner), creating a holistic and intimate portrait of his working process. The book offers not only gorgeous studies of Kundig’s signature details and integration with natural landscapes, but also a record of his refreshingly straightforward voice.

Tom Kundig took a moment to answer a few of Archinect’s questions about his background, his evolving business sensibility, and the surprising intimacy of gizmos.

Archinect: Is there a particular moment or experience that you credit with being the first time you considered becoming an architect?

Tom Kundig: There were actually a lot of moments not to become one, because my dad was an architect. I struggled for many years with not wanting to be part of that culture. It was a slow process to become energized about it.

A: You became a part of Olson Kundig in 1996, thirty years after its founding by Jim Olson. How has your practice, and the firm as a business, changed in your time there?

TK: Over the years since I was hired, we’ve gone from seven people to 150 people, which has changed everything. This growth has very naturally expanded the personality and direction of the firm—we’ve brought in new ideas and new people. Jim allowed me to take part of the firm in a new direction, which is not typical. Now, were are letting others within the firm, including fellow owners Kirsten Murray, Alan Maskin and Kevin Kudo King, to expand our practice in new ways.

A: Many of your residential projects convey a balance between subtle, precise details and vast, immense landscapes. Client preferences aside, how do you characterize the relationship between a home’s detailing and its landscape?

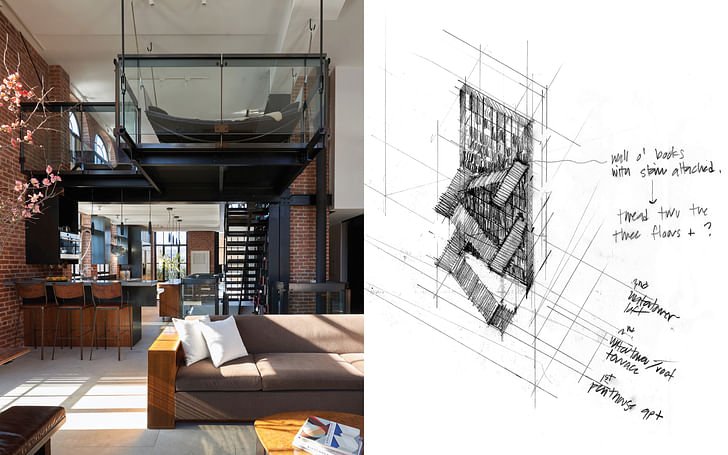

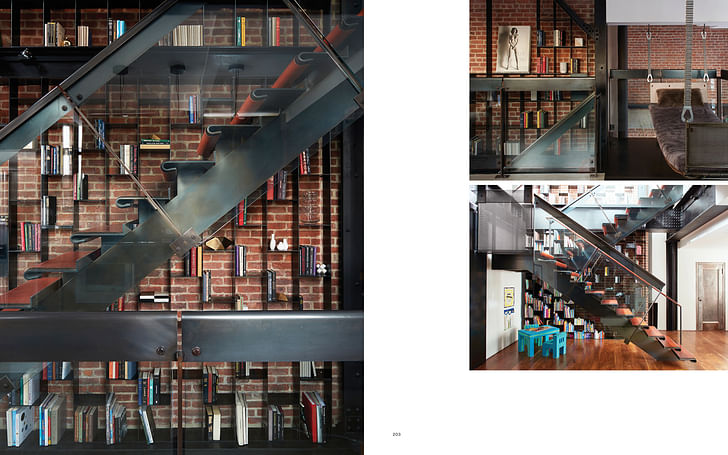

TK: A home’s detailing and its landscape are very similar. Even immense landscapes are based on microscale moments and a well-designed home is its reflection. There are large-scale and small-scale situations inherent in every site, whether it’s rural or urban; as an Even immense landscapes are based on microscale moments and a well-designed home is its reflection.architect, you fold those macro and micro influences into the experience of the home. That’s what architecture is all about.

A: What initially provoked your interest in including “gizmos” in your architecture?

TK: I grew up in a culture of devices in the extraction industries of mining, logging and farming. I also worked with Harold Balazs, an artist who used simple machines to move large sculptures. His use of engineering devices—pulleys, levers, or bags of sand—to move steel fascinated me. These basic engineering solutions inspired me to move large-scale things, much bigger than us, within architecture. It made me consider the relationship between the human body and built form.

A: How do you imagine the “gizmos” influencing a resident’s / user’s relationship to the project?

TK: Gizmos create an intimate connection between the body and the building. Using the body to activate the building directly connects humans to the built environment around them. When you can physically interact with structures—move, morph and change them—it alters and enhances the way you experience a building.

A: In 2000, Olson Kundig opened an in-house interiors studio – what brought about this decision, and how has it affected the firm as a business overall?

TK: Ever since Jim founded the firm, there has been a deep relationship with interior design. We have never seen it as being separate from architecture, so it was a natural step for it to evolve into an internal discipline. Having interiors in-house allows us to work more seamlessly and have projects look and feel as if they were designed holistically from the inside out.

A: Many of the projects presented in “Works” are single-family homes in majestic, seemingly isolated landscapes, however you’ve also completed projects in Manhattan and other urban areas. How does your approach to designing for domestic life in an urban setting differ from designing for a more rural one?

TK: Our work has always been context-driven, whatever that context is natural, cultural or built. Designing for domestic life in an urban setting is largely based on the common human It’s about how we provide prospect and refuge, no matter the context.needs of intimacy and extraversion—these needs follow us wherever we go. It matters less whether the project is urban or rural and more about how we, as architects, draw on it specific context to create spaces that feel authentic and human in scale. It’s about how we provide prospect and refuge, no matter the context.

A: Speaking more generally, how have the priorities of residential design, of domestic shelter forms, changed in your time practicing?

TK: We’re seeing a demand for smaller forms overall, more intimate spaces, places for people to gather, particularly with family. As design has become more a part of everyday life, we’ve also witnessed a desire for more precise considerations of detail. The accessibility of well-designed objects and a growing cultural appreciation of architecture has played a role in how our clients think about design.

Tom Kundig: Works, by Tom Kundig, available now in hardcover from Princeton Architectural Press.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

2 Comments

Impressive designs!

impressive! thank you..

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.