In this feature Bartlett student (and Archinect school blogger), Chris Hildrey, discusses some critical issues in the architecture industry, such as the core sustainability of the practice of architecture, as it relates to other industries, and unpaid labor. He also takes us to a fun London architecture event to show us the sweeter side of our profession.

If you happened to be walking through Bloomsbury in London last month, chances are you would have noticed a trail of Gingerbread Men stickers peppering the pavements in place of the usual litter, pigeons and AA pavilions. Following the breadcrumbs, you'd have found yourself at the Brunswick Centre and the Incredible Edible Gingerbread House - a life-size gingerbread house created by alma-nac in aid of Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity.

Never having paid much attention to fairy tales as a child, I dismissed the fate of previous breadcrumb-followers and set about following the trail. Luckily for me the only obstacle waiting at the destination was a 100-deep queue of children and parents. But, being sure to have my camera in full view to give the (almost entirely true) impression that I was there for architectural photos rather than marshmallows, the crowd was soon negotiated and I was free to step over the threshold and down the stairs into another world.

At first, it came as a surprise to be heading downwards. For something with such visual potential it seemed a shame that it would take place in a basement rather than in full view of the shoppers outside. But on turning at the landing and stepping down into the dimly lit grotto it all made sense: placing this world in the display-case of a shop window would have shattered the illusion. This was a mixture of small-scale architecture and theatrics; it doesn't belong with the normality of the everyday. It was reminiscent, in fact, of the lessons familiar to every architecture student - those of processional spaces and thresholds; lessons so often reduced to diluted gestures in everyday practise but shown here to still be important and powerful when used in the right context.

Having negotiated this descent into another world and arriving at the basement level, the first thing that hit me was the overwhelming sense of activity. Immediately to my right was a crowd of children being entertained by a clown; in the far corner a gingerbread-making class; and there, in the middle, was the gingerbread house itself - the front hinged open for a story-telling.

Story time over, the task of refocusing my brain to architectural matters began. This was not easy. First, there was the challenge of acclimatising to the energy in the room (not helped by the fact that you could eat just about anything that wasn't load-bearing); while secondly, there was coming to terms with the fact that it wasn't just the children struggling to contain themselves. At one point I turned around the back of the house to see a fully grown man joyously scooping up fistfuls of Smarties from the garden plant pots. As our eyes met, he froze in a shameful paralysis more suited to a man caught eating actual gravel. We clearly understood each other though and, sharing a conspiratorial nod, I joined him in indulging a childhood fantasy.

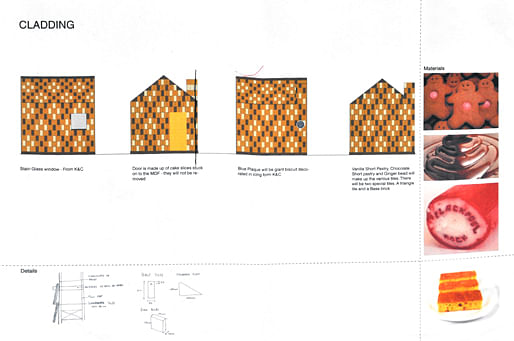

Soon though, with the sugar-high inevitably wearing off, it was time to look at the built work. I was struck by the sheer level of detail. It's here that it becomes clear this was designed by architects. With the project being small and the architects acting as joint designers and contractors, there were few of the usual constraints found in the normal construction chain to which most of us have or will become accustomed. And they clearly took delight in the process, taking every opportunity to lavish the project with finishing touches.

Though the main structural shell of the house was made from MDF (somewhat dry and lacking in flavour), it was hidden behind an undercoat of chocolate - painted on to darken the gaps between the gingerbread shingles. Belgian waffles were applied across the interior for acoustics, flowers were made from Haribo with edible insects nestled around their base, and curtains were made from candy bracelets - while flurries of popcorn popped from the chimney. There was even a nod to architectural humour with Battenberg slices carefully positioned to show the section of battens at the hinge openings. The closer you looked, the more components there appeared to be. If God is in the detail, he's going to need a toothbrush.

However - and call me cold hearted if you will - what really excites me about this project is not so much the details or the shrieks of delight from kids gorging themselves on marshmallow waterfalls, but rather the fact that architects are doing this at all.

Recently, the RIBA think-tank Building Futures released a paper called The Future for Architects - a report examining current trends and expectations on where we will be as a profession by 2025. Though it was based on a fairly small, albeit very qualified, London-centric survey sample, one observation that really stuck out was the notion that "in ten years we probably will not call ourselves an architecture practice, it will be something else entirely". Now, this quote came from an architect at a 'small metropolitan boutique practice' and could easily be put down to their specific trajectory within the profession, but I can't help thinking instead that it's an important symptom of a fairly widespread trend throughout architecture at the moment: the increasing divergence between those who see themselves as 'architects' and those who see themselves as 'designers'.

For it seems that the sad truth is that the economic realities of architecture have created a cul-de-sac for the profession whereby those wanting to remain as architects are forced to abandon elements of design once thought central to the whole undertaking, while those who wish to maintain the discipline of design are forced to diversify to the point where the title of 'architect' becomes irrelevant if not a hindrance. In both cases, the validity of the traditional notion of the architect is called into question.

But what are these economic realities? Under financial pressure, all businesses are forced to react or risk failing. I remember back to geography class as a teenager and being taught about farmer diversification in the UK. Land that was not reaping enough profit was being used for tourism or quad biking instead, or old farm houses were converted into bed and breakfasts. As of 2010, 50% of farms in England have diversified outside of farming, 23% of which get more from their alternative activities than from actual farming. Farmers were faced with a failing business and they reacted by changing their modus operandi.

Now, architects are not failing in the same way as English farmers were; at least not as obviously. Though many have struggled in the recession and jobs are harder to come by these days, there are still a great many who have managed to negotiate this particular downturn. However, whether you look at the lucky ones in hard times or even the profession at large in boom times, I'd argue that there's a near-ubiquitous deception giving false confidence in the success of the architectural business model: the reliance on unpaid overtime.

As part of my current research at the Bartlett, I'm looking into the economy of architecture. Originally, this was specifically into the causes of unpaid overtime within architecture and began from the fact that most days I, like many students and professionals in architecture, hear or feel frustration at the working conditions. This frustration often takes the form of hushed complaints or talk of underappreciated architects but either way, it stems from a simple fact: that in most cases, in order to create a built work, unpaid overtime is required. Some would say this is the nature of a profession; I'd argue it's the nature of a failing business.

The real danger of this unpaid overtime is that it masks the economic failings of the traditional model of architectural practise, artificially creating an illusion of economic viability. And, though the divergence mentioned above seems to be a reaction to redress these failings, we also have to ask: why is there such a deficit between the cost of labour required for architectural practise and the market value of the result of that labour?

Frequently when faced with such questions, other industries are rolled out against which to judge architecture - most commonly the automotive industry and product design. However, there's a degree of irony in using these other industries to try to strengthen architecture through comparison. Because the very ways in which these industries prosper are the ways in which architecture, in its traditional form, cannot. Furthermore, in trying to emulate the methodologies of these other industries in an attempt to economically activate the profession, it's the profession itself which is fundamentally changing as a result and the validity of the title 'architect' which comes under threat.

There are two important differences between the likes of the automotive/product industries and architecture: those of clients and mass production. Both of these factors make the process of design efficient and valuable in ways that architecture can't hope to match without fundamental changes to our modus operandi. While companies in these sectors have historically been able to afford to invest years of man-hours in the research and development of an iPhone or Ford Model T knowing that the user experience will make a real difference to the value paying customers will assign to it, architects are stuck with the fact that most clients are not the end user and that, with the exception of private residential projects, the entity responsible for assigning market value to their work does so with a language of quantitive assessment and almost complete personal detachment.

The qualitative benefits which we as architects are educated in such as considered spatial design, materiality, phenomenology or just plain ease of use make no clear difference to the bottom line. We work to include these touches because we believe in the difference good architecture makes, while the end user generally appreciates, or at least benefits from, these considerations because they live in and around these designs. But these benefits are often un-demonstratable to an external observer such as a client and, with their having no reason to foot the bill for something which isn't demonstrating quantifiable added value, often result in architects working to satisfy the interests of themselves and the end user without the financial endorsement of the client.

These unpaid man-hours add up. There's a tendency to think of 'design' as something found in the concept stage of a project, but as anybody who has had to put together a tricky detail will tell you, design is present in every decision. From shadow gaps to material specification to choosing a door handle: these components come together to make the whole, and the consistency and choreography of these elements is what makes the whole greater than the sum of its parts in terms of overall experience and subjective assessment of quality.

So, with architecture often unable to market the considerable work involved in adding qualitative benefits, they face the second hindrance in comparison to automotive/product design industries: mass production. For architecture is an inherently bespoke service more akin to a tailor than a product designer. While Apple can fire up their Shenzhen factories and start a production run of their latest product - each one making the R&D investment that much more efficient - the architect is forced to repeatedly go back to the drawing board to consider a new site, a new client and a new brief.

This method of working is clearly unsustainable and adaptation to this fact is already visible in the profession, from the business models of branded architects to the sole practitioner reusing what details and suppliers he can from job to job: each is attempting to benefit from economies of scale in a service that is often marketed with the USP of being able to provide uniqueness.

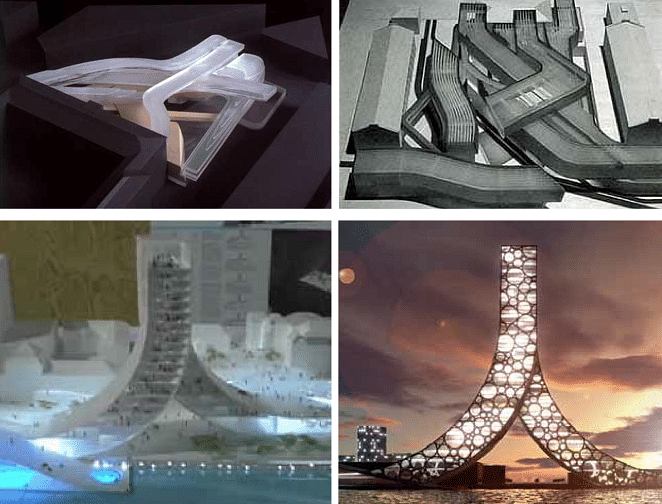

This reaches an absurd point when looking at projects such as Zaha Hadid's Contemporary Arts Centre in Rome or BIG's REN scheme for Shanghai. Comparing these to previous competition schemes (Reina Sofia Museum extension in Madrid and a hotel scheme in Sweden, respectively) reveals the acute lack of uniqueness in these schemes otherwise heralded as iconic despite their origins being openly described by the architects.

But what these schemes lack in bespoke problem-solving they make up for in efficiency. And while many architects, myself included, would complain of the potential dangers this holds for a profession which prides itself on bespoke-ness, they are reflective of the constant need for standardisation and efficiency within architecture if any hope of leveraging a suitable market position - and thus operating a viable business - is to exist.

And herein lies the divergence in the profession which seems to be taking hold between 'architects' and 'designers'. With the former aiming to satisfy quantifiable market values through standardisation and efficiency, design inevitably gets worked out or - when it remains - pushed into unpaid overtime. This working method will be all too familiar to any graduate who has entered the profession only to find that the working methods learned at university are rendered almost entirely useless. They find themselves working on competitions and staying late into the night or being put on CAD monkey work to see through the repetitive task of coordinating components of building systems.

The 'designers' (especially those without brand status and the fee premium that brings), however, find themselves unable to sacrifice their raison d'etre and are therefore faced with having to either operate in an economically irresponsible way (through unpaid overtime or running at a loss) or diversify and spread their creative output across other sectors in an attempt to make use of the skills developed through their architectural education and so often described as 'useless' by practitioners.

This brings many benefits: first, for graduates there is a more immediate pay-off from the massive financial investment in the skill-set built up through university; secondly, these skills often lend themselves to disciplines where the benefits of mass-production can be taken advantage of; and third, the benefits of this work are more often directly understood by clients, leading to work which is so often financially unrewarded in the architectural market adding real value to the service.

This is why seeing a gingerbread house in a London basement can get me excited: it makes me realise that maybe all that design education doesn't need to be put to the side after all. That perhaps, after all is said and done, there's the chance to be a designer with this degree. But what's more, with this divergence seeming to run along the dividing line between larger and smaller practices, it's important and liberating to know that a conscious choice can exist on which route to take.

7 Comments

nice piece chris.

our office is small and we struggle just with the problem you are seeing. to be designers or make standardised buildings so we can earn more $.

we are taking the position that we cannot stand out in the tokyo scene without spending time on the design side and anyway it's what we want to do going forward. I think it makes more sense with larger projects, but i can see no way to get to the larger projects without learning how to design better with smaller ones either. do you think firms in the uk are really giving up on design, except for when gingerbread is involved?

excellent piece and quality observations. thanks for the post

hi i want go bartlett.

i bake house at bartlett?

plese help me where go to thak you

great piece, chris.

Untangling the web of agendas between client, architect and end user is clarifying but I'm a little confused about your main point. You seem at first to be ambivalent about the split fate of architects and the erosion of professional legitimacy but then come out strongly for 'designers'. I think it's clear that design is squeezed out of formally commissioned architecture and fudged back in through unappreciated overtime, but I don't see how the 'designer' side of things is meant to relate to this situation of professional legitimacy. It might resolve the blues you get after graduating uni by giving you the kudos that you don't get in the office (an issue of personal legitimacy?), but that's not the same problem that faces the profession at large - those financial pressures still remain and professional legitimacy is still being lost.

The reuse of designs by big firms is more complex. As a response to market pressures and, being part of the process of making buildings, it is also a strand of architectural creativity. Whether it's the best that we can do is another discussion but what we need to find are clever ways to get good things built. In this vein I'd like to suggest that the graduate's exchange of gratis labour for recognition in realising something like the ginger bread house is part of the spectrum of shrewd procurement that gets you a starchitect's remaindered maya shape at the other end of the scale.

Is this an ambush? or a bartlett vs AA article?

There is some subconscious stuff going on here. The first sentence reads about "litter, pigeons, and AA pavilions." Why would these items be put together in the same sentence?

Are we supposed to believe that a gingerbread house designed for little to nothing (by the authors fellow Bartlett students) is supposed to be an example of possible new models for the profession?

The middle part of the article is most interesting, but neo-Venturian humor I'm not too fond of. The main agenda we have is to create a demand for getting good architecture built. Im inclined to think that nature of the NEW architect would benefit from more scientific approaches.

Chris, although this is a convincing observation of the status quo, I think you are drawing the distinction between designer and architect without taking into regard current 'hybrid' practice models that do not segregate architectural production from design, but in fact use the former to drive a larger part of the latter. Mass-customization, UN Studio's writings on 'design models' and practices such as SHoP come immediately to mind. The design model is prototypical, can evolve and can be implemented in various situations and projects. Going back to the drawing board for each client, site, or project does not necessarily produce better designs, and I would go so far as to say it has never been the most productive method for architects in the qualitative sense. The fact is, designers often repeat themselves, not always with dubious intentions such enhanced brand recognition and better market value, but because certain sensibilities develop and a certain vocabulary starts to emerge. I envision a profession in 2025 that strives to fully reconcile this dichotomy.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.