We’re perched high above Santiago de Chile in an unassuming meeting room, near the top of a nondescript office tower at the base of the famous San Cristóbal hill. Visually-speaking, we’re as far away from the architecture of Smiljan Radić as possible. There are no boulders or found objects, just a wooden table separating us and some relatively simple chairs. “Why should an architect have to design furniture?” Radić asks with a laugh, gesturing at the furnishings. “There’s enough of it around already.”

Radić’s eyes drift to the small window in the corner of the room. From where I’m seated, I can see the largely barren backside of the hill, the possible future site of the architect’s first tower. Across from me, Radić has a clear view over the city, which is covered by a thick grey mantle of particulates and water vapor. Except for when he jumps up to fetch a model or look for a site plan, Radić tends to keep his eyes locked on Santiago as we talk.

"How was your experience working with the Serpentine?” I ask. "It was really good," Radić replies before correcting himself and laughing. "I can say it was really good after the storm.”

Before his participation last year in the Serpentine Galleries’ annual pavilion series, hosted in London’s Hyde Park, Radić was largely unknown outside of his native Chile. Radić has no online presence outside of what others have posted – not even a website. The architect has no online presence outside of what others have posted – not even a website.

Upon its unveiling, Radić’s 2014 pavilion – a donut-shaped, translucent fiberglass shell perched on a cluster of boulders – was greeted with equal parts confusion and wonder. “This summer's Serpentine pavilion is the weirdest ever,” read Oliver Wainwright’s headline for the Guardian. Robert Bevan of the Evening Standard described it as something between a “giant egg” or a “Stone Age spaceship,” “a symbol of hope and something more mysterious.”

“My pavilion was really weird, you know?” Radić says with a hint of defiance. “Everybody said, ‘Oh you could do what you want.’ No, excuse me, I did what I could do.” In this case – and in general with Radić’s works – form was born between possibility and necessity, a mode of working that seems to feed off the technical and bureaucratic constraints that other architects decry.

Radić tends to get involved in just about every aspect of the construction process. This means developing a relationship not just with the engineers, but often the construction workers as well, sometimes to the point of instructing and supervising their work. Admittedly, this isn’t always a choice. For example, when constructing his “House for the Poem of the Right Angle,” he worked with just two other people – neither of whom had any expertise working with concrete.

My pavilion was really weird, you know? “I spent my holidays just making drawings on the site and explaining to them how to do it, how to do the concrete,” Radić tells me. In the end, they did the house “badly” – a quality of which he seems proud. But, before you start wondering about the structural stability of his works, it’s important to note that in Radić’s parlance, “badly” is a synonym of “brut,” “rough,” or “heavy.” It’s a signature of his aesthetic (met in equal parts by a continued interest in fragility), but also a practical necessity in Chile, a country with a tradition of self-construction that he considers an important inspiration as well as practical advantage.

"You could build a big building, but you'll always have the opportunity to do something handmade: changing options, changing materials – because here you don't have stock,” Radić explains. “You have to bring the stock. And then the building gets delayed for eight months, so you have to stop and change properties of the material et cetera. Some things are really fixed, but – this is in both really big buildings and small buildings – you are really on the project.”

[In Chile] you'll always have the opportunity to do something handmade Even with his first European commission in Hyde Park, Radić took what mounts to an unusually active role in the construction process. During what he describes as frenetically-intense visits to London, Radić worked actively with the engineers (as well as curators), including traveling to a quarry to select the stones himself. While in Chile such a visit would be both necessary and relatively easy, in London new and different challenges arose.

"If I did that here, I could have more control,” Radić explains. “Because if I did it wrong I could go to the quarry and choose another stone and it's no problem. But there it was really – ‘we don't have money, choose nine stones, you have to be really clear about it, okay let's go.’”

For an architect who tends to work intuitively and in situ as often as possible, one day to select his stones created a fair degree of stress. "If you put, for example, small rocks, the fiberglass is not floating, it's just really heavy,” Radić explains. “If you put a really huge rock, the fiberglass could appear like a decoration, you know?"

In Chile, it’s better to do it really brut rather than try to do it perfectly “In Chile, it’s better to do it really brut rather than try to do it perfectly,” he notes. “And here to do something brut it's cheap, but in Europe it's really expensive.”

And Europe has structural and safety requirements that Chile doesn’t, which also translates into different expectations and perceptions of a design. With his hands, Radić described the difference between a structural wall in London versus one in Chile – a norm of between 40-60 centimeters in the former, compared to as thin as 12 millimeters in the latter.

“Perceptions are really different depending on where you are,” Radić explains. “And this you have to have in your mind when you are projecting something.”

“The [experiential] quality of fragility changes depending on where you are,” he continues. “Thomas [the engineer] said to me, ‘Oh we need forty millimeters of skin.’ That is nothing for them, that is really thin too. But I said the transparency is not really coming and it will be more opaque, just an object, you know?”

Perceptions are really different depending on where you are While the donut form as a whole was largely self-supporting, necessary apertures threatened its integrity. Rather than thicken the walls, Radić found a solution in the bricolage practices of his home, where “when something is coming to collapse, they put some sticks and the skin of the structure will just stand up.” Hence, his pavilion ultimately had an interior support system that included two columns.

This anecdote is in many ways symptomatic of Radić’s design process, which tends to mine from vernacular practices, is keenly attuned to the local specificities of a context, and fluidly adapts to issues as they arise.

“Always you have to manage this kind of thing in projects,” Radić says. “The discussion with the engineer and with the producer was really important, more than just to understand the project, but to also understand the project for them too.”

Later, I ask Radić how the experience has changed his career and his practice. “I always say that after you design for the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, you feel you could do anything around the world,” he replies. “Because, maybe this is really small, but the relations with the people, with the builders, with the engineers, will be similar.”

[The Serpentine] is a great opportunity, but it’s really stupid if you think that you are then in with the best At the same time, don’t expect to see Radić building super-block sized complexes in Beijing. He maintains that he prefers and almost only works on small and medium-sized projects. He has a humble demeanor, remarkable both within a profession known for oversized egos and for an architect whose work is increasingly critically acclaimed.

“[The Serpentine] is a great opportunity, but it’s really stupid if you think that you are then in with the best,” Radić states. “You have Sejima, Nishizaws, Koolhaas, Herzog de Meuron – you are not part of that club, you know? This is a closed club.”

Before receiving a visit from Julia Peyton-Jones, co-director of the Serpentine with the energetic and omnipresent Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Radić admits he did not know much about the commission, which counts among its alumni some of the most noted architects in the world, including several Pritzker Prize winners.

At first he assumed that the curators were performing a requisite tour of the global south. “[For events like this], they always have to go all the way around the world,” Radić says. “But in the end they [always] choose something from the North.”

[The Serpentine pavilion is] a dialogue and you are talking about architecture. When he received a call announcing that he had indeed been selected to design a pavilion, Radić had to ask them to send an email instead. “Hans Ulrich talks too fast,” he says with a laugh. “And Julia’s English is too proper for me to understand.”

"I'm really flexible, in general, but the process is too short and it's too stressed,” Radić tells me. “But at the end I understood: this is a dialogue, it's not – they don't call you and say, ‘Oh give me your best thing and do it,’ you know?”

Actually, it wasn’t until this summer, during a panel on the occasion of the opening of Selgascano’s 2015 pavilion, that the “meaning” of the Serpentine Pavilion came into focus for Radić. “The important thing is: two curators called you, in one time – in a specific time – for a specific site, to think about architecture. And that is really important because your relationship with the curators is not the same as with a client. It's a dialogue and you are talking about architecture.”

It's to talk about architecture through your architecture. Radić continues, “The important thing is that they chose you because your architecture could give them the opportunity to talk about global architecture, or the architecture in that time, at that moment.”

“And the pavilions are this: to talk about architecture, not to talk about your architecture. It's to talk about architecture through your architecture. And that is really important.”

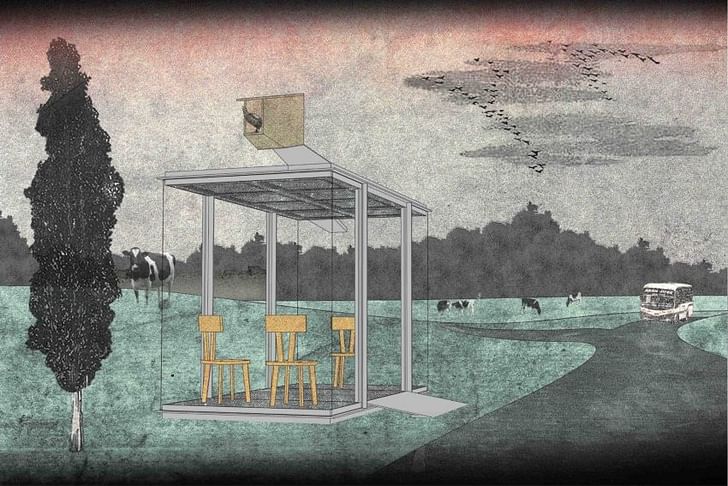

After finishing his pavilion, Radić made one more work in Europe: a tiny bus stop for the Austrian village of Krumbach. He was among seven other well-known international architects asked to design a structure in exchange for a holiday there.

This is to be an architect... to send things and then they appear perfectly “That was so funny because it was the first time that I've felt like an architect, I mean a real architect,” Radić says with a laugh. He sent them a design and was asked for only a few minor details regarding material specifications. A few months later, Radić received a photograph of the structure, perfectly realized.

“This is to be an architect, you know, to send things and then they appear perfectly,” he says. “I think that this building – this bus stop – was the first time I was not involved in the construction.”

Perhaps like all others in Radić’s profession, the platonic ideal of “the Architect” hovers like a ghost over his shoulder. Although, in the case of Radić, it is met with a great deal of criticality, self-deprecation, and humor. You might even say he moves in opposition to it.

Like all architect's the platonic ideal of “the Architect” hovers like a ghost over his shoulder For example, Radić is currently engaged with a tower project. “It was really important for us,” he explains, “because for architects, a tower represents, ‘I’m the architect, I’m the architect of the city, you know? I will the architecture of this city.’”

Submitted for an international competition for a site on San Cristóbal Hill, Radić’s design counters the normative architectural tendency to use a tower as a mark on the urban landscape. Rather, he conceives of it as a “ghost of a tower,” a structure that will appear fragile and even verge on disappearance on cloudy days (it will be made of a greyish steel).

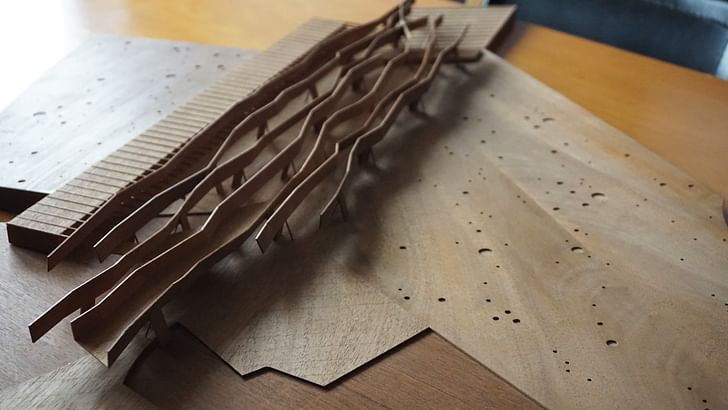

Based on an idea originally conceived for a show at Tokyo’s Gallery Ma, Radić’s tower is a tensegrity structure, designed using specially-created software. While visually the tower appears supported by an internal shaft, in reality the shaft is not structural. Radić describes the design as “like a marionette.” Normally the architect wants to make a mark, and we called this tower a ghost because it’s really fragile

“Normally the architect wants to make a mark, and we called this tower a ghost because it’s really fragile,” he relates. “You think it might fall down, you know? And you really don’t know how it’s going up.”

Integral to the design of the “ghost tower” is a keen attunement to the site, no doubt informed by its close proximity to Radić’s office.

“For us, if you put something really heavy here, the hill would appear to be coming down,” he explains. “We tried to keep the hill as the real support.”

Still, Radić admits he’s drawn to the “checklist of architecture,” and is currently entering another competition for a bridge design. In typical Radić-fashion, however, this is also a bit outside the norm: a restoration of an old train bridge, rather than a new construction. “It could be really beautiful, I think,” he says.

Radić relates the importance of fragility as a concept in his work. Architecture, he contends, usually works with the “limits of security,” whereas, by contrast, art tends to work with the “limits of insecurity.” While an architect must maintain a building’s stability, they could do well to draw on theater, which revolves more around the construction of an ambience and the exposition of the relationship between the individual and his or her context.

Later in the week, Radić was planning to open a new events space in Santiago, perched on top of a neoclassical building. It’s beautiful to have this contrast... something stable and something ephemeral Limitations imposed by the municipal government precluded any hard construction, so Radić took a softer approach.

“We are building an experimental dancehall that is a restoration,” Radić explains. “But we are going to put a circus on top.”

“The beautiful thing is you have this room – this modern or contemporary room – but on the top you have this primitive one. It’s really fragile, you have to throw it in the trash in five years because the material is not really strong, but [it only] costs about $6000. It’s nothing and then you have four hundred square meters for $6000.”

“It’s beautiful to have this contrast, you know? Something stable and something that’s ephemeral, and then if the local government says, ‘I don’t want this on the top,’ then,” Radić snaps his fingers. “Okay, let’s throw it away, no problem.”

the material or the forms always have some history On the other side of San Cristóbal Hill from the proposed site of his “ghost tower,” Radić has another project for an events space. Like with his solution for the structural integrity of his Serpentine pavilion, he drew on Chilean vernacular practices, in particular the branch-roofed shelters used on farms.

Radić’s wife, the sculptor Marcela Correa, is the closest thing he has to a design partner, and he consulted with her closely on the design of the event space (and with all his projects). He explained their preference for working directly with objects and models rather than in abstract or theoretical terms.

“For us, the material or the forms always have some history, sometimes really poor or sometimes really deep, but some history, some social history,” Radić states. “For example, I could not explain this project without talking about the branches on the farms that the poor people use, and the shadows [they cast].”

Admitting he probably “explains things too much,” Radić invoked the work of the artist Gordon Matta-Clark. “It's a cut in the house, what else do you want? That's really powerful.”

You always do some damage to the landscape, but you have to try to do the least damage that you can “I explain things too much because [I want to] create a new history,” Radić pauses for a moment. “But normally they're not true, you know? It's about the history about the object, it's not the object.”

Radić’s gaze again returns to the small window and mine follows. Someday soon, Santiago’s second-tallest peak, now primarily a large park of crisscrossing trails and forest, may be adorned by two of his structures. As far as architectural interventions go, they’d be barely perceptible.

“You always do some damage to the landscape,” Radić relates. “But you have to try to do the least damage that you can. And that is really important. I always think about this.”

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

5 Comments

I like this guy. Thanks for the interview.

I'd say though this statement could equally apply to works by many other more prolific architects today: While an architect must maintain a building’s stability, they could do well to draw on theater, which revolves more around the construction of an ambience and the exposition of the relationship between the individual and his or her context.

thumbs up

I've said it elsewhere but I really like the image for that BUS:STOP in Krumbach... It is great you got to do the interview in person. Just as a process/experience, I have always found it so different than a phone/skype one.

I like the idea of "brut" architecture...Everytime I see some Dezeen perfect clean line house I want to mess it up...like when my kid has perfectly combed hair...

Hi, I am an Indian architecture student and am really impressed with Radic's work and ideologies which came out very clearly in this publication. Since he does not have any digital trace, kindly help me understand as to how to contact his studio if i want to work with him as an intern.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.