If the current exhibition at Los Angeles’ Architecture + Design Museum was titled by a sarcastic person, it would be called "Work/Life Balance: Pshaw!" As it is, the infographic-laden collection of vinyl banners loosely mounted to stacks of brown boxes, co-organized by Gensler and UCLA’s cityLAB, is called "Work on Work", and it is both the history of and the proposed future for society's daily grind. And man, what a grind it is.

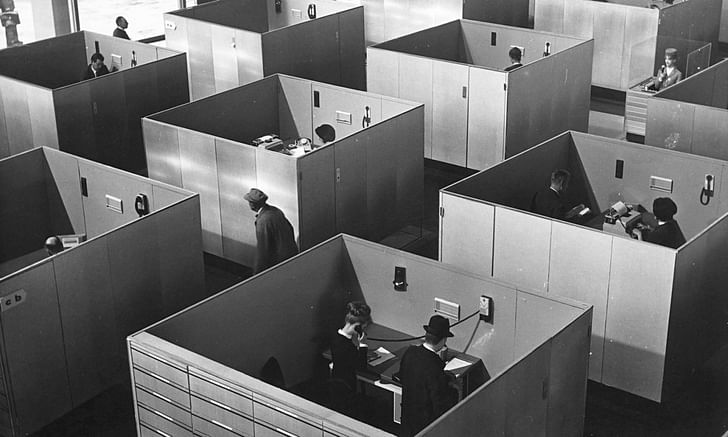

The exhibit begins with a series of vinyl banners detailing the history of work-related architecture in Los Angeles, divided into three principal scales: desk, building, and city. The first banner dates back to the 1780s when the city was freshly founded and little more than a plaza, but quickly delves into a detailed 232-year history of building typologies and technologies specific to work culture, such as the factory, skyscraper, office park, cubicle, and typewriter. Gensler & Co. apparently asked themselves: How can we design work environments so employees never have to worry about having independent thoughts?With research principally by cityLAB/UCLA students and design principally by Gensler, the banners mark events such as "Entry into Vietnam" and "Rodney King Beating" to help situate the viewer in time, while each major innovation in workplace design has its own date and pictorial accompaniment.

Walking from left to right, the visitor tours the history of downtown Los Angeles’ major development in the 1880s and subsequent shuttering in the 1970s due to extremely high percentages of un-leased office space, along with the destruction of cheap multi-tenant 19th-century residential houses in the city's core. Things reach a desolate zenith around 1975, but downtown revives again in the "Digital Era," a period of time the banners attribute as being from 1980 to 2012. This section of the exhibit, which includes a few vintage advertisements for the first cell phones circa 1987 (only $1,499.00!) is informative, even delightful, until a bold statement appears like a slap in the face at the end of a champagne brunch: "Working in public becomes the model of engagement with wider urban society, and the middle classes abandon the public sphere and allow its institutions to wither."

By attributing the withering of the public sphere solely to the "middle classes," this statement forgets recessions, municipalities that were starved for income due to generous corporate tax breaks and outright tax fraud, Reagan-era social program cuts, and the effects of globalization on blue-collar jobs which primarily supported and sustained the middle class (those wage-earning cut-ups!). Perhaps it's simply poor phrasing, but the statement's remarkably limited perspective neglects entire swaths of history, making the exhibit feel less like a thoroughly researched showcase of student work and more like blatant PR for corporate entities keen to land-grab.

This feeling of being at an un-airconditioned business conference is not helped by the next section of the exhibit, in which the banners stop talking about history and start getting real about Gensler and cityLAB's speculation on the future of the work environment. “Open Expo”, the product of team of UCLA students, kicks off a series of gradually unveiling modular systems, in which tracts of open land including parking lots are slowly repurposed in tightly designed modular units. This is fascinating from a design perspective, but depressing from a human one. While the historically-oriented vinyl banners Apparently, accounting ran the numbers and taking in the sunset is a loss leader at bestdid observe that the work/life balance ratio had begun to erode in the late 1980s due to technological breakthroughs, the future-oriented vinyl banners transform this observation into a design mandate, eagerly eyeing the last bastion of non-work-related free time, The Commute. Under Gensler and cityLAB's direction, the students seem to be asking themselves: How can we design work environments so that employees never have to worry about having independent thoughts? Well, “Hypermobility” starts by adopting the Silicon-Valley-inspired series of interlinking Wi-Fi-equipped buses that pick up various workers at transit hubs and shuttle them into a continuous, non-site-specific work voyage. The UCLA-student researched and Gensler-executed design is clearly meant for people in their younger decades: an infographic traces the day of a worker who alights at LAX, is promptly swept up into her communal "mobitro-LO" work bus, and then after being dropped off at a hub in Downtown L.A. for meetings, "finishes early, [and] enjoys LA nightlife" with a disco ball and friend. Another very So-Cal plausible case study includes a midday break for surfing.

“Open Expo” is geared toward “knowledge-workers,” defined as a creative class of musicians, performers, and artists, and attempts to “connect two of the city’s most underutilized resources: untapped real estate and a wide spectrum of work types.” This sounds good in theory, and the modular design does seem like a cheery if cut-rate version of what Bjarke Ingels and Thomas Heatherwick are proposing over at Google HQ; a variety of spaces that plug in to foster interaction as much as room for individual creation. The only questionable aspect of this particular project is that it proposes sourcing underutilized land, such as parking lots and abandoned lots (worryingly delineated with a biohazard symbol), to build the modular models. Again, a great proposal in theory: but who sets the guidelines for what constitutes “underutilized”? One person’s “underutilized” is another’s “space the neighborhood kids play soccer in on weekends.”

Next up, the mission of "Urban Desk” is to "transform the last remnants of public space into sites for work: the sidewalk, the alleyway, and the park." Wait, what? At what point did our public spaces become extensions of the work environment? Apparently accounting ran the numbers and taking in the sunsets is a loss-leader at best. "Urban Desk" is a modular case study, a five-year build project that starts off with an electric plug on the side of a building in year one and ends up at year five with a shaded outdoor desk, a bathroom, a kiosk, and a small stage for performances. As the small print states: "Recognizing that not all workers or all hours of a workday are appropriately suited for outdoor work, this project sets up a process of transition and incentivization for the sidewalk and other public spaces by deconstructing rigid social norms about the inferiority of office work." Hmmm. First of all, why does work need “incentivization” to start being held in public spaces? Also, the statement “rigid social norms about the inferiority of office work” is so packed with assumptions, social class markers, and inadvertent conditioning that...well, let’s put it this way: if you grew up in a family struggling to make ends meet, landing a steady office job that keeps a roof over your head is hardly considered inferior.

If even our parks are just the backdrop for an outlet and a punishing deadline, is there any room for humanity?It should be noted that while there's nothing wrong with flexibility and adaptability, the idea of taking for granted a permanent erasure between the public and private realm is troubling on a number of levels. It indicates a shift into a forced multivalent urbanity, where the notion of structural identity (a space for contemplation, a space for work, a space for relaxation) is permanently blended into an indistinguishable mass, a kind of unmemorable civic smoothie. Design like this may serve many masters, but its very multifunctionality renders it anonymous. Where does the intrinsic character of a city dwell? If even our parks are just the backdrop for an outlet and a punishing deadline, is there any room for our humanity? Or have we just collectively given up on the idea of creating urban spaces that take into account the fact that not everyone comes from the same walk of life, and may not have the money to take private vacations to distant lands? As in, people may actually want to enjoy the place they are in living in, as opposed to simply working in it?

Naturally, the mixture of freelance workers, performers, and freshly incentivized office workers look merry in the “Urban Desk” renderings. There's a juggler who looks a bit like Dana Carvey, where the notion of structural identity (a space for contemplation, a space for work, a space for relaxation) is permanently blended into an indistinguishable mass, a kind of unmemorable civic smoothie.and a breakdancer spinning on his head underneath a band of clean-cut singers and guitarists. Taken at its best, the Gensler/cityLAB-supervised student plan is an attempt to replicate the organic bursts of life that vibrant cities naturally create. Of course, the exhibition's focus on Los Angeles in particular changes the dynamic: this is a city of hard-workers who, at least by popular imagination, are largely happy to spend hours of each day in their cars away from any notion of public space whatsoever. But still. Part of what has given Los Angeles its recently renewed vibrancy is the reclamation of public spaces as places in which you would actually want to be. In the last decade alone, the sidewalks in downtown L.A. went from motor-oil drenched tumbleweed boulevards to thronging urban nightspots, in part because of cheap rents and a burgeoning art scene. People thrived because they were allowed and helped by the city to adapt the space to their wants: parklets, seating on Broadway, and designated neon green bike lanes, among other innovations.

And that's where, all historical gripes aside, the exhibition has a sliver of merit: the new economy is indeed heavily freelancer-driven, and the students are keenly aware of that. The rise of app-driven companies that base their model on people buying and selling services when they want to points to a far more flexible, less rigid model of work. There's nothing inherently wrong with creating a more adaptable environment, but the privileged and oversimplified overtones of the exhibit, paired with its refusal to envision a more distinguished balance between productivity and (unstructured, unmonitored, human) downtime make it a bit chilling. This is the "Work on Work" vision for the future of work: you can opt in, but never out.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.