When Kevin Roche speaks, you should listen. Roche is a hero of the long-game – during his sixty-five year career in the U.S. (and counting), he has trained or worked alongside seminal architectural vanguards Charles and Ray Eames, Mies van der Rohe and Eero Saarinen, and on projects for such heavyweight clients as the Federal Reserve, MIT, Ford, Deutsche Bank and IBM. Still practicing today at age 92, Roche is a force to be reckoned with, thanks to an unflagging work ethic and realist approach to the profession’s shifting tides.

Roche’s career took off in the 1950s, when he worked at Eero Saarinen and Associates shortly after completing graduate studies at the Illinois Institute of Technology. When Saarinen died in 1961, the firm was passed into Roche’s hands, where it became Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates LLC. Roche finished a handful of Saarinen’s most well-known projects, including the Gateway Arch, CBS Headquarters and the TWA Flight Center at JFK, and then went on to design numerous institutional and corporate headquarters, museums, and educational facilities worldwide. He has served as the architect for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Master Plan for over forty years, overseeing its expansion and installations. And in the midst of all of this, Roche’s work garnered a Pritzker Prize (1982), the AIA’s Gold Medal (1993), and the Gold Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1990), among other awards and accolades.

While Roche has been established in New Haven, Connecticut since first working with Saarinen, he did not start there. Born and raised in Ireland, Roche studied architecture at University College Dublin, and worked for a short stint in Dublin and London after graduating in 1945. He left to study with Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1948 – just a year before Ireland officially became a Republic, shedding its Commonwealth ties to the United Kingdom.

I spoke with Roche in March, Skyping him at his home-base in Connecticut from a hotel room in Manhattan. Throughout the hour-long interview, Roche’s slightly wavering voice explained in no uncertain terms his thoughts on the profession today, sharing reflections and analyses (and even some jokes) hard-earned through decades of practice. We previously published the interview in two parts on Archinect Sessions – here, you can listen to a series of Roche’s most salient thoughts from the interview.

Our interview began with a look at the role of the architect in the overall building process – from concept to construction to completion, where does the architect stand? Since the beginning of Roche's career in the 1950s working with Eero Saarinen, the professional milieu for any architectural project has diversified and shifted, in ways not necessarily advantageous to the architect. But for Roche, the centrality of the architect has always been paramount, as the single person responsible for the concept behind any structure.

To Roche, a project's success depends on that key concept, arising from an individual – concepts formed by the group are inherently compromised. After a point, involving more people in a project will only dilute and confuse its execution, leading to Roche's admission that he is no fan of the middle-manager:

Roche's career really took off when he became an indispensable part of Eero Saarinen and Associates, eventually taking the firm over with John Dinkeloo after Saarinen's tragic death – at age 51 of a brain tumor. From Roche's account, Saarinen's energy and talent were undeniable, as was his devotion to his work. Below, Roche explains what it was like working with him:

While Roche's firm has worked with some pretty heavy-hitting clients on comparably large projects, he does admit that they sometimes struggle to find work. As the media landscape has changed so drastically within the last couple decades, so has marketing, and architecture is publicized very differently than when Saarinen presided. Roche acknowledges this, but still isn't too jazzed about the rise of the "public relations person" in architecture.

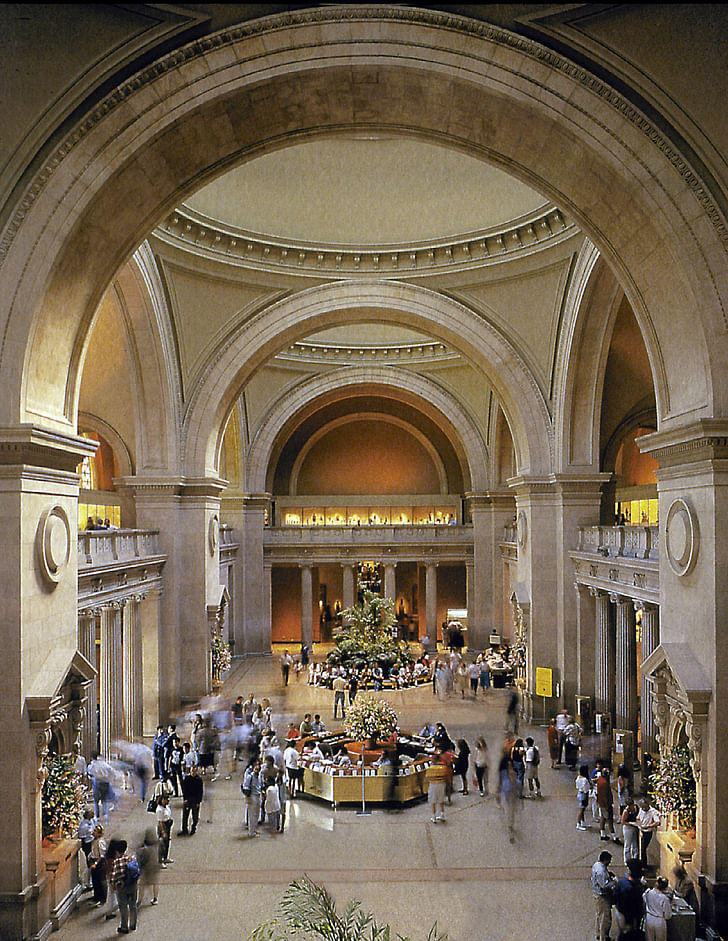

Roche may perhaps be best known for his corporate structures, but his firm's work with museums has led to some of his most impressive projects to date – specifically, his expansion work on the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and designs for the Oakland Museum. While museums tend to be one of the most highly trafficked projects, a must-see destination for tourists and locals alike, they're also some of the least-appreciated, according to Roche. People are too busy paying service to the art inside to appreciate where its housed.

Aside from those who only passed through Roche's buildings on vacation, there are those who live their professional lives inside of Roche's offices. The ball pits and espresso bars of today's oft-photographed workplaces seem like a true paradigm shift – until you consider that when Roche set out to design Cummins' HQ, there were no such things as "workstations". Roche and the firm had to go to Mexico to find a design for the individual work modules.

The firm's work for Cummins also challenged traditional office hierarchies, by divvying up the floor equally among workers – whether new-hire or manager.

Despite having overseen the drastic shift in office mentalities that came in the latter-half of the 20th century, Roche is not convinced that the office will further adapt in the digital age. Working is about productivity and efficiency, and now that so much can be done remotely, why force people into offices at all?

When I asked Roche to extend his reflections into the future, to try and predict where the architecture profession is headed, he responded soberly. He did not seem at all convinced that things in the world were better now, overall, than they were when his career began. And to think that now, we are on the right track, doesn't fully acknowledge the premise-altering shifts in how we build human societies today.

Historically, the core organizing principle of the city, according to Roche, has been commerce. Cities are commerce incarnate, but that model is fundamentally compromised – cities also provide context for the core of human activity. Divorcing the city from commerce could allow it to become further devoted to serving human society, attending to its higher potential.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

2 Comments

I have always liked Kevin and his work. He was one of the people whom drove me to the profession. He designed a fantastic building for Worcester Mass, which went on the chopping block and never really became his vision. I have bounced around a lot but ended up in the Yankee State Years ago and have never had the good fortune to bump into him.

It is on my bucket list!

Would have loved to get a response from him to this quote

"Absent from the exhibition is the hand of the master. Aside from a beautiful rendering from his school days and one vitrine with a set of small sketches for the Ford Foundation Building, there is no evidence that Kevin Roche ever drew. I mean this not as a criticism, but an observation on the nature of Roche’s practice and means of architectural production."

Via review of Kevin Roche: Architecture as Environment exhibition, by Belmont Freeman published at Places.

Later goes on to discuss the importance (and perhaps privileging) of model making over drawing...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.