Working out of the Box is a series of features presenting architects who have applied their architecture backgrounds to alternative career paths.

In this installment, we're talking with Abraham Burickson, founder of Odyssey Works.

Are you an architect working out of the box? Do you know of someone that has changed careers and has an interesting story to share? If you would like to suggest an (ex-)architect, please send us a message.

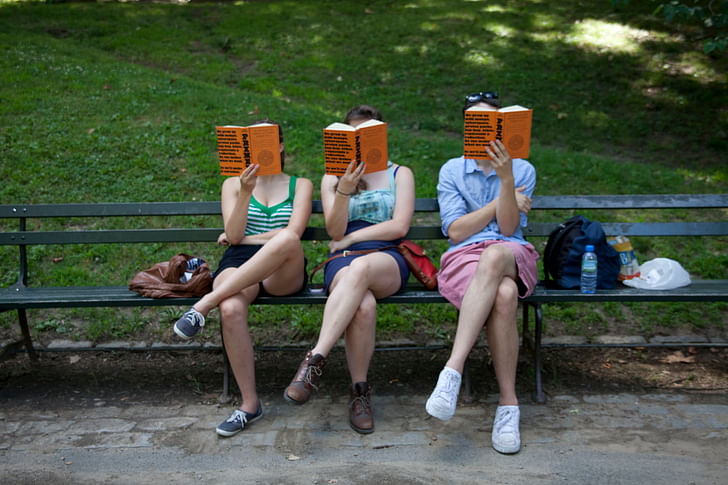

Simply put, Odyssey Works is an art collective that stages days-long performances for an audience of one. Their productions arise from months of intense research into that one audience member’s life, played back out at them in a tumult of happenings tailored to that person’s identity and existence. Abraham Burickson studied and worked as an architect before founding Odyssey Works in 2001, and it has played a formative and collaborative role alongside his architectural life ever since.

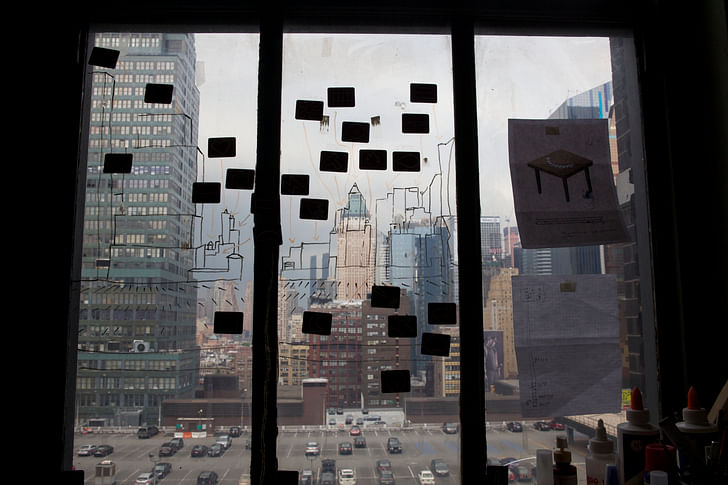

The production of an Odyssey Works piece is fundamentally collaborative and architectural, drawing creative inspiration from one person’s idiosyncrasies to build experiences into the physical environment of their existence. In addition to Burickson, the Odyssey Works team is composed of artists, poets, programmers, playwrights, dancers – all contributing an interpretive and practical role in putting on the Work. A single Work requires a spectrum of designers to create or modify any variety of “props” and “set pieces”, terms that Burickson doesn’t necessarily use but that will populate the objects and spaces of the performance. These could be anything: a wooden shack, a web page, a piece of choreography, an antique book. In a single phase during a performance, participants have been blindfolded and bound to a tree, tasked with holding a piece of meat for hours, and awoken by a fabricated talk show.

Working in a medium that is at once wholly immersive but ephemeral, personal but collaborative, moving and inimitable, Odyssey Works captures many of the struggles that arise from the modern era’s art historical legacy. The intermedial influence of Fluxus is writ bold, as is the Surreal exegesis of psychological interpretation, and the Situationists’ derision of capitalistic viability. Odyssey Works moves out of the industrialization of culture into something inefficiently sublime and sublimely inefficient, that when documented dissolves into digital dematerialization, only to then come around to a re-materialization within another new, semi-virtual reality, for another person entirely.

Given the momentous investment of time and energy required to pull off such a production, they do not happen often, but documentation from the few referenced here refer to "When I Left the House it Was Still Dark" (New York, 2013), “The Map Is Not The Territory” (New York, 2012) and “The Narrative Spiral” (San Francisco, 2012).

What made you become interested in architecture?

I transferred into the architecture school, because I wanted to try and create experiencesIt’s funny that I’m talking to you from Istanbul, because this is where architecture started for me. I went to school originally to study English and anthropology, then I left and came to Istanbul during my first year, to learn about the whirling of the whirling dervishes, and while I was here I spent the whole time wandering the city. It was kind of an unexpected, wondrous surprise, to find a place like this, and I kept wandering into mosques and of course time and time again into the Hagia Sofia, and I was continually surprised and impressed by the profound effect that those spaces had on me. When I returned to school the following year, I transferred into the architecture school, because I wanted to try and create experiences, at least in some way related to the experiences that I had in those mosques and in the Hagia Sofia and wandering through the narrow streets of the old city, and Galata district in Istanbul. So here I am again, exactly twenty years to the month since I was inspired to pursue architecture, and I’ve been revisiting some of these places, and they’re still amazing. They still inspire and move me. And when I say move I mean it in that sense that, when you actually enter into one of these spaces, you feel you were in one place in yourself, and you step into the space and you discover that you are now “moved”; you are in another place in yourself. That to me is at the core of what architecture can do. So it’s great to be back here and seeing that all over again.

Where did you study architecture?

At Cornell University, a BA in architecture. After that I worked briefly at Kohn Pedersen Fox in New York, then for a bunch of small firms, and then after that, I apprenticed in the trades for four years, and then returned to architecture to practice on my own. Then built up a practice and eventually started teaching architecture, and about thirteen years ago now I co-founded you discover that you are now “moved”; you are in another place in yourself. That to me is at the core of what architecture can do.Odyssey Works with a friend of mine, Matthew Purdon, and we just started this as an experiment to explore ideas that we were mutually interested in, and it kind of got out of hand, to the point where it’s the major focus of my life now. I still do teach and I still do have some architecture clients, but I would say in a way that the major part of my architectural interest and explorations happen inside of Odyssey Works now, although certainly in my practices as an architect and in my teaching as well.

So for the past 10+ years you’ve simultaneously been practicing, teaching, and running Odyssey Works?

I’ve been running Odyssey Works since 2002, and I’ve been teaching since 2009, and I’ve been working on my own since 2005. There was a trip to grad school in the middle there.

What did you pursue in graduate school?

It was an MFA in playwriting and poetry.

When you graduated with the bachelor’s, did you intend to continue studying and practicing architecture? How did the poetry degree come along in your architectural trajectory?

There are like 25 different ways. There’s something that I’ve learned from architecture that I think is not necessarily unique, but that an architecture education uniquely emphasizes, and that is the holistic understanding of a practice. That when you’re an architect, you have to not think just about a structure, not just about your clients, not just about the city, you have to think about the aesthetics, you have to think about the way sound works, you have to think about all the collaboration that happens, you have to consider an entire life that is going to occur because of an intervention that you’re making, which has a pretty narrow scope but a broad set of reverberations. And these reverberations manifest in many different ways, so there are different ways of approaching the same set of ideas, it’s this idea of performance, or the way what we do in the world, the things we create, activates what they come in contact with. Poetry, theatrical performance, architecture, whatever else, is all of a piece, to me. It’s a question of trying to use manifestations in the physical world to sculpt experiences in the lives of the people who come into contact with them. And so, when thinking about it that way, it’s actually something in line with the practice of architecture, because we’re taught now, at least the conversation is there, that what we’re designing is not necessarily just the form, but performance, and the effect that the form creates. I see all these things as just different ways of approaching that, and that’s why I’ve been walking down different roads in the same direction.

you have to consider an entire life that is going to occur because of an intervention that you’re making

Take poetry, for instance; if you look at the history of poetry, if you look at what poetry means, it comes from the word “structure”, a poet was a “maker”. Or if you go down the linguistic path, and it’s about understanding structure and understanding rhythms, and it’s about considering the way a person moves through an experience, if you want to think of it that way. Similarly, theatrical performance and playwriting is about a way a person moves through an experience, all time-based art is about that, and so is architecture. I never felt like I left any one thing and went to a thing. And I haven’t left any of these; I still write, I still design, and I still direct, and to me they’re of a piece.

How would you describe your role in putting on Odyssey Works? Describe your current profession and your role at Odyssey Works.

I’m the artistic director of Odyssey Works. I make it happen. It’s a collaborative effort, so I don’t make the pieces, I just bring the group together, and the buck stops with me, but we work collaboratively. I’ve played around with different structures over the years, in terms of how we can make this work, but the way it generally happens (now I’m the only director, Purdon has since moved on to more lucrative things), is basically there’s a group of people theatrical performance and playwriting is about a way a person moves through an experience, all time-based art is about that, and so is architecture.called the “structure team” that gets together at the beginning of every project and conceives of the overall structure of each piece. We’ll spend four months or so getting to know our audience as well as we possibly can. It depends on the size and scope of each particular piece, but we have to do this intense amount of research, and that’s a workload that this structure team collaboratively shares, and then my job as artistic director is to structure that investigation. It’s something we all do. At the end of that study period, after we’ve spoken to everybody in their families, spoken to their husbands, wives, lovers, friends, enemies, therapists, gone to work, seen their home, read a book they’ve read or written, watched their favorite movies, gone as deep as possible into their material, until we didn’t feel like we could know them any better, then we go intro retreat somewhere for anywhere from four days to a week, and we consider the person and we ask the question: in what way may we move this person with our work? How can we reach them, and how can we understand their subjectivity in a way that the work we wish to be making can be as deeply received as possible.

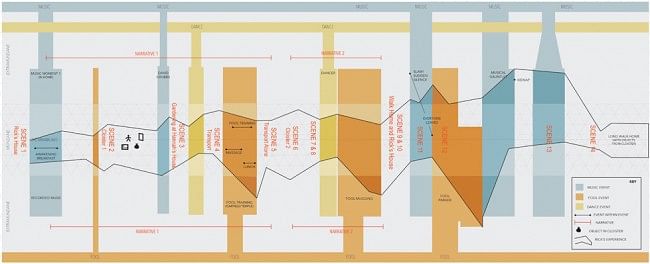

We do this together, that’s a collaborative effort, and out of that retreat we emerge with not even a set of scenes, but a structure of states of experience that we wish this participant to go through. And this is generally manifest with the diagram, a kind of map of the performance. So, for instance, we wouldn’t necessarily say that “we need this person at this point to be buried alive”, but we’d say in that diagram, “an experience of intensity, perhaps confinement”. So that’s the structure or the state of the experience we want our participant to have. We develop that from the beginning to the end. But then we go back to work with the rest of the team in developing the rest of the scenes in detail. So it’s a different process than, maybe, A bad architect is an architect who doesn’t give a shit about the person who’s going to be living therewhere you sit down and do scene one act one and you see your act through. Maybe it’s more like, to go to architecture, making a massing model…

So my role is to just guide that, but not be the one making all the decisions. And so then I play a role, depending on what’s needed of me, sometimes I’ll act, usually I’ll act as myself, the Director of Odyssey Works, and sometimes I’ll just stay behind the scenes.

How do you see your architecture education bleeding into that? Do you feel that there’s something specific that you’ve gained from the design education of an architect, and how it influences your role in Odyssey Works?

Absolutely, it’s pretty much inseparable. But just to highlight a couple: what I mentioned before, about this linking… I mean the primary thing is this mode of creativity where you consider your audience first. A bad architect is an architect who doesn’t give a shit about the person who’s going to be living there, so long as he gets to create his beautiful masterpiece and if anybody messes with it, he blows it up. A good architect is somebody who understands the people who are going to be using the thing that he’ll create, and designs it so that the life that’s lived inside their building is the one you hope to be lived there. So it’s a mode of creativity that starts at the end, it starts with the audience and goes backwards towards the creation. That’s how we do it at Odyssey Works, that’s the basic structure, and that emerges directly from ideas in architecture.

The overwhelming experience of architecture school is how absolutely and completely immersed you are in the material. For me, that was the primary experience, and much more important than any aspect of pedagogy or material.Another thing is that our work is entirely site-specific, we never do anything in theaters – maybe once or twice in theaters, but that was site-specific as well. Largely our work is in cities and in public space, quite often. The way we use public space, the architecture determines what the performance is going to be. So instead of defining what’s going to happen, we’ll go to specific sites of relevance to our participant, and try to read those sites, and understand what performance can happen there. So we’re in continuous dialogue with the architecture, and with the urban space. That’s a second way that my architectural life influences the performances. A third is the diagram, which is kind of a beloved tool of the architect, and is something that I myself have found incredible for breaking down the traditional notions, the A-Z approach to the creation of narrative, and looking at performance as a set of relationships, which is what the diagram allows you to do.

The overwhelming experience of architecture school is how absolutely and completely immersed you are in the material. For me, that was the primary experience, and much more important than any aspect of pedagogy or material. It was the act of going all the way in, continuously, and not letting it be just a compartment of your life but making school the center of everything. It was very clear that, if you’re going to get anywhere new, if you’re going to create anything of value, you were going to have to put in effort that was above and beyond the ordinary approach one had to school and classes, where you mete out your time in hours and structure something that works for you to create, to write that paper or do that assignment or whatever. Architecture school required total commitment, and in Odyssey Works that’s the case as well – absolute, total commitment. Because otherwise nothing new is possible, and it’s almost not worth it, that was the other thing I walked out of architecture with, that it’s not really worth it to go into any project without a total commitment. That’s true when you’re working by yourself, and it’s multiply true when you’re working in a collaborative project, and much of architecture school and all of architecture is collaborative. With a group of people it takes quite a while until you get into a group flow, but once you do, amazing things can happen.

Architecture school required total commitment, and in Odyssey Works that’s the case as well – absolute, total commitment.

Do you feel the investment into digital technologies in architecture education compromises or hinders the architect’s ability to fully immerse themselves?

That’s a big question. It’s a whole other conversation about the dematerialization of our culture, which my work is absolutely pregnant with, and incredibly important for architects who create material culture, although there are some who move outside of that. At the risk of becoming a Luddite, I do feel something is lost in the move to the computer. I don’t feel that the iterative potential is destroyed. You can model a lot more on the computer than you can by hand, so there’s a lot more potential there. With the laser cutters and 3D printers and all these technologies, it’s possible to iterate at a scale and a speed that certainly we weren’t even close to when I was in school, and that wasn’t that long ago. And that’s a great thing. So I don’t feel that the potential for iterative design processes is hurt. I do feel that the move towards dematerialization in the design process is really harmful for an architect, because we are people that are relating to the physical, and my own personal experience is that I have to design by hand and then move to the computer. But that has to do with the way I was trained, I’m sure, because I see my students work much more intuitively with the computer, and are able to design on the computer.

For me, there’s a quality to drawing and to building a model which is in a platonic parallel relationship with the actual structure; so that you’re in relationship with the building that you will be building physically in the moment of creation. It seems possible to me to be thinking in a design way to be drawing by hand, but not to be able to do so while using a mouse. I hope, think, and suspect that the technology could comprehend this at some point, and move to a point where, again, the presence of designing on the computer is more kinesthetically related to the process of construction. It seems like I can’t be the only one thinking this, and hoping it gets there. Certainly, for instance, working on 3DMax or even Revit is a lot closer in the kinesthetic experience than AutoCAD, or whatever it was … which was so much more command based and text based, and so much less about seeing and relating to the structure. I feel like the architect’s knowledge might be moving in that direction, but it might be a long way off.

What in your work with Odyssey Works has influenced your teaching and practicing architecture? Has it made you a better architect?

At Odyssey Works, we get really, deeply into the way our audience sees the world. We try to get past opinions, and down to the level of experiencing consciousness and the kinesthetic response. It’s been an exercise in understanding empathy in a complex way, rather than just sort of feeling whatever a person feels, to relate to their emotional life, this is trying to step We try to get past opinions, and down to the level of experiencing consciousness and the kinesthetic response.It’s been an exercise in understanding empathy in a complex waycompletely into their body and emotions as much as possible. And understanding that the physical is irrevocably linked to the emotional, the spiritual and the intellectual, in the way people experience the world. This has been incredibly useful information for me when approaching architecture clients, and trying to see the power of imagination necessary to project their lives into the future, in some built space. And to try and bring them along with me, as I do that.

I hope I’ve been able to trace some of this perspective with students as they start to approach questions of how architecture affects us, in our lives. I think that’s my role as a teacher, is to understand the relationship between what we create, what we design, and the life lived in it. To practice a kind of empathetic imagination as a part of their architecture/design practice.

Are you reading any poetry now that you’d like to recommend?

I just can’t stop going back to George Oppen. He’s as far as I know the greatest mostly forgotten poet of the 20th century. He inspired and mentored the Black Rock poets of the 1960s, really interesting character. He wrote a poem, forty-part 20-page poem called “Of Being Numerous”, and I have yet to discover a better piece of writing. I’ve probably read it 100 times now, and every time it unfolds more.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

3 Comments

This was a great read, and I really appreciate the very close links to architecture and daily experience that somehow moves you out of a set mindframe and into a new one. Mr. Burickson is an excellent example of how it can be beneficial to get degrees in (or learn a lot about) other disciplines and apply a more general knowledge to our experience of living in a built world.

It does creep me out to imagine being a participant being studied, though. It reminds me of this amazing short story by Stephen King called Quitters, Inc. It reads a little old-fashioned, because smoking is not as common as it was then, but it's still incredibly chilling.

A very virtual physical or physical virtual. The future here now?

Reminds me of the Michael Douglas movie The Game, albeit a bit less action packed perhaps...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.