It’s foolish to think of process as a straight-line; tangents, detours, dead-ends and roundabouts are the foundation of architecture's process, however immaculate its presentation. PLACE-HOLDER, a publication out of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto, focuses on the messy preamble and sequels to architecture, publishing those fringes of architectural practice and study that otherwise might be sheared away.

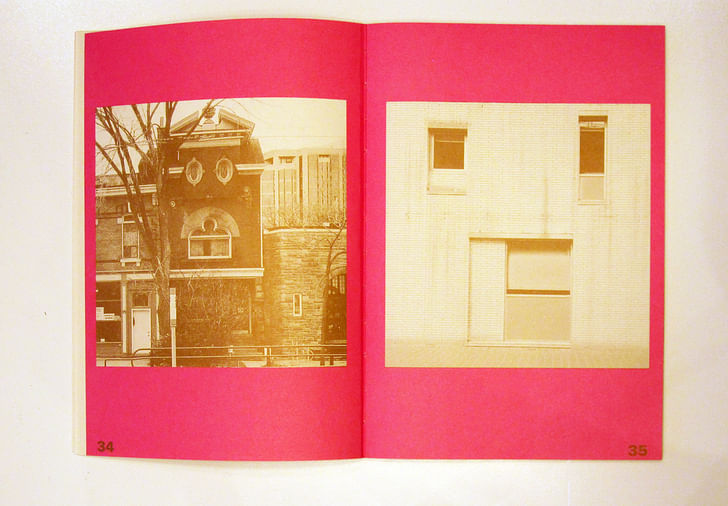

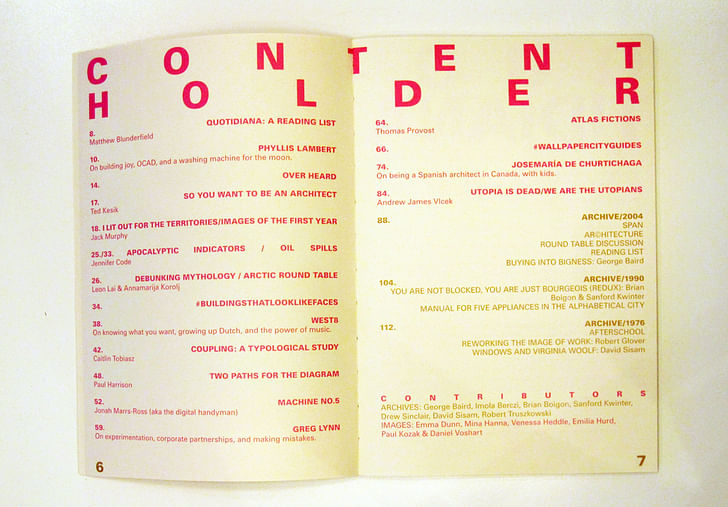

Founded in 2011, the “deliberately subjective, dated, inclusive, influenced” publication has since put out two issues, and we’re featuring the second, “AFTER SCHOOL”. The so-called Issue 1/2 takes a look at the things that may seem out of architecture’s wheelhouse, but in the end prove themselves as major influencers – in short, the life around architecture always bleeds back in. The issue features interviews with Phyllis Lambert, Adriaan Geuze and Josemaría de Churtichaga, along with essays, poetry, and photos by students and others. For Screen/Print, we’re featuring the interview with Greg Lynn.

Lynn is the owner and founder of Greg Lynn FORM, author of Animate Form, and Professor at the University of Vienna and Studio Professor at the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA. Conducted moments before his lecture (“Carbon Dating”) at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture at the University of Toronto, Lynn speaks with editor Roya Mottahedeh and contributors Mark Ross and Paul Harrison about experimentation, corporate partnerships, and making mistakes.

PLACE-HOLDER: To what degree are you interested in experimentation, or play?

Greg Lynn: I try not to play around, ever. [laughs] I try to work at a conceptual and theoretical level rather than looking for happy accidents. Whenever I’m approaching a tool or technique I anticipate its use and principles in advance. The term “experiment” that was so popular in the nineties—for me, having lived through it—was shorthand for handing over of responsibility of design control and vision to software and hardware, and hoping that something good would come from it. This might be acceptable to do once, learn, and then begin to work in a different, more motivated way. When I see the same particle flow experiments for the tenth year in a row, I become allergic to “letting the tool do its thing and trying to interpret it and read into it.” It could be that it is an introduction to design that everyone needs to go through; like the nine-square-grid problem. But I really became hostile to that approach. Especially because from those unmotivated experiments a style emerged that has been adopted by corporate and wannabe corporate practices who can’t explain to themselves or others what they are doing I try not to play around, ever.and why things are the way they are, other than through an appeal to the intelligence of software; an intelligence that doesn’t exist without an architect’s concept and vision.

Now, in my teaching I work in partnership with Boeing, Disney Imagineering, Cirque du Soleil, Red Bull, and Nike. They are cultural innovators posing interesting questions to architecture and urbanism, and they demand concepts in order to have a discussion, as they are intimate with the uses of software and experimentation, and what an architect might refer to as an experiment they see as a lack of ideas and a deferral of creative responsibility. These partnerships are uncharted as a model of creative practice and in education. I wanted to bring my experience from practice to the students as I see a crisis in education all over the world. I think it is important that my students not become service providers only but also are able to become cultural leaders, intellectuals, and are capable of talking with clients about innovations in culture and not just in construction, as this can be done in a vocational setting and not a University. It is strange that most practitioners and even some academics assume that what we are doing is asking companies for money to buy robots. Instead, I ask them for their time, and that is the hardest thing to get. The discussions and experience that the leaders of these companies bring to the discipline is amazing, and because the students haven’t spent too much time in practice they are less focused on minimizing risks and defining scope of services and more interested in expanding the role and responsibility of the creative professional. For me that’s a very new model of education. I personally don’t think that it is experimental as I have clear expectations that are being validated already about this new practice.

Do you think you’ve been attracted to that new form of education or exploration because architecture is slow to move?

There is such a funny gap between what people think architecture is doing and the reality of what architecture has been up to, which is more and more focused on delimiting scope and becoming a service subsidiary to the construction industry. That disconnect, that gap, is very strange. For today’s students, bridging that gap is going to be their biggest problem. For my students from the nineties, the model of success was to become a mini-corporate practice through the access to digital tools for design and construction, which I find very ironic. The most successful students and employees of mine from that time are the people that are becoming the new corporate practices. Architecture is becoming more and more a vocation and so a lot of architecture schools are becoming vocational training centers for professionals There is such a funny gap between what people think architecture is doing and the reality of what architecture has been up torather than training leaders in the world of ideas and culture. For me, as someone that had some part in this transformation and focus on digital technology, it is my biggest regret, as I had the pleasure of being mentored by a generation of cultural figures and creative innovators. Architecture is not the place for those personalities anymore and the action has moved into other fields that think of themselves as a place for so-called ‘creatives.’ There seems to be a backlash against vision and innovation from within our field and instead a celebration of normalcy and mediocrity.

In Animate Form you were interested in the perception of movement as opposed to literal movement. Are your “Future Primitives” a progression away from that sort of mentality, or a physical manifestation of the ideas that you might not have been able to achieve at that time?

When I was using animation software and modeling software that had rendering and spline surfaces built into it, there was an immediate response—from journalists more than theorists—that if you used animation software, you must be talking about buildings that would move. Similarly, if I made a rendering during the process of design, there was an assumption that the building should look like an unarticulated amateuristic-rendered surface, in my case. I was a little bit resistant to that knee-jerk reaction and just said, “Well, I’m not looking at motion that is literal, I’m looking at motion that is phenomenal, or a sequence of things that has motion imbued in it;” Wölfflin’s Baroque idea of motion. When I saw the first self-driving car on the road a few years ago, I started to think that architecture should have a response to that; the built environment could probably be a little more clever. [laughs] I’m bored out of my mind with industrial robots replacing carpenters and welders. I’m working to get the robots connected with volumetric limits so they know where they are in space. This makes me rethink everything from furniture to building envelopes, floors and walls to conventional mechanical elements like doors and windows. I’m more interested in getting the robots into the buildings than I am at using the robots to build the buildings.

You have a more multidisciplinary approach (we hear that you have a naval architect next to a robotics specialist). How does that influence the way you approach a project?

When the recession was hitting, I looked at participating in competitions, particularly in China, under worse and worse terms. I was rethinking my practice in terms of what I wanted to do and under what circumstances. First thing I realized; I don’t like doing work for free. The situation is more and more exploitative of architects internationally and so instead of spending money to do competitions, I spent the professional nest egg I had squirreled away on other things that had more value to me and to my practice, in my opinion. I thought: When is the best time to invest in research? If you have the ability, you do it during a recession—you can do a lot more for a lot less. For the last four years I have consciously focused on returning to motion, and thinking about getting robotics embedded into buildings. I also have had an intuition about composites and new kinds of materials for more than a decade, so I also focused on that. It was for the office, but actually I was the one that was getting trained in that There seems to be a backlash against vision and innovation from within our field and instead a celebration of normalcy and mediocrity.stuff so I could understand what the issues were. I knew it was where things were going, so I was interested in going there and seeing if I could help shape how it went. Becoming an early adopter of software, I feel like I was able to shape where some of that went—at least to make a space for myself to occupy—and I’d like to keep doing that. A person in the corporate world who I was consulting for once told me: “You’re here because you are able to predict where the future is going,” and I said “Well, actually, no, I am not predicting anything; rather, I am able to influence people with ideas that have future potential.” [laughs]

Do you think traditional building technology is bad, at this point? Where does your architectural interest in composites (and especially plastics) come from?

Well, the materials are honest, genuine and applicable to today. Clearly, there are opportunities for lightweight, recyclable, logistically-interesting approaches to building. Instead of stacking a brick—which turns out to be the worst ecological material—I thought: What would it be to look at really lightweight construction? I also wanted to engage the whole interest in bricks. With Nader [Tehrani] and Monica [Ponce de Leon], and Matthias [Kohler], and all these people, I just thought: what’s with all the bricks? People think natural materials are really good, but for example, once wood has been treated for the pests and moisture, and it has been cut into standard sections and lengths for shipment, and it is delivered from one place to another on boats and trucks, and when it has been cut and trimmed, it ends up becoming not the greatest if you are into “authenticity” and “sustainability.” It is counter-intuitive culturally to use a plastic product, with sand burned in a nuclear facility to make a fiber. It sounds really bad, but when you look at carbon fiber, you use so little, it lasts so long, and it’s so easy to transport that without even looking at performance it is incredibly sustainable and makes materials everyone thinks of as wholesome and good like wood and brick look pretty profligate and inefficient. I don’t see a lot of excitement about building steel, brick or glass bikes, cars and other performance products that need to conserve energy and be efficient.

Given our issue’s theme of AFTERSCHOOL, we’d like to know about your transition into practice.

I’m probably old school in the sense that I worked for Peter Eisenman for five years and Antoine Predock for six months once I graduated. I worked at Arcosanti for a summer while I was in high school where I met [Paolo] Solari, and got a taste for construction. I really enjoyed working at Peter’s from 1988 until 1994. When I did start teaching, I didn’t teach in order to start a practice, I taught to learn how to teach and to develop some ideas that could sustain me for the rest of my career. I went out to Chicago for a year, with Catherine Ingraham and The step after school was much more important than what school I went to.Bob Somol— there were quite a few people in Chicago that Stanley Tigerman had brought in, and I knew Stanley was a really good teacher. Then I went to Columbia University and pretty much learned how to teach for about three years. So I opened an office a decade after graduating from Princeton and after having already edited and written a book about other people’s work.

So you saw an opening that wasn’t being fulfilled, that you could actually step into?

I was in no rush to have an office, frankly. I actually wanted to make my mistakes under the mentorship of somebody else. What I really feel like I learned from Peter was how to work with a client. You wouldn’t necessarily associate Peter with being a charmer like you would Renzo Piano; to put it nicely, he can be abrasive. But he is really, really good at getting people who make decisions feel like they are part of the idea. I would never have learned that on my own. When I look at some of my colleagues who didn’t ever work in somebody else’s office, you see that it is a very hard learning curve.

Is there anything else you wish we had asked you?

One thing: most of the successful architects that I know had a project for themselves when they graduated from graduate school. When I did my thesis at Princeton, it wasn’t like I knew everything, but I was beginning to work on the difference between different types of curves, I was beginning to work on how to think about surfaces, related to structure, but all the things I’m still working on were all laid out when I was in school. The step after school was much more important than what school I went to. Everybody thinks that’s your biggest decision. It’s not. It’s what you do the year you leave, and how you nurture your plans from school to get through the next ten years.

Issue 1/2: "AFTERSCHOOL"

Editors: Elizabeth Krasner and Roya Mottahedeh

Associate Editor: Anna Gallagher-Ross

Designer: Pham Khoung Duy

Advisors: Jeannie Kim, Hans Ibelings, Anita Matusevics, Shawn Micallef

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured PLACE-HOLDER.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

"Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.