Unlike those architects who long to be thought of as artists, Byrne is an artist who loves to thinks about architecture. Like the deadpan docent of the infrastructural realm, David Byrne's work has inadvertently helped make architecture into a pop culture staple. While his commentary may not be mind-blowing to an architect, the method of his commentary – the diversity and size of his audience, the innovative visual and aural techniques in which he conveys highly abstract concepts – is a major contribution to architectural discourse.

Very few popular songwriters have as many instantly hummable, building-oriented tunes in their catalogues as David Byrne. It's way beyond "Burning Down the House"; take a closer look at the entirety of Byrne's 38-year output, working with Talking Heads, Brian Eno or any of a dozen other musical collaborators. Instead of writing love songs that focus on interpersonal rapture, Byrne tends to frame his romanticism in potentially isolating structures: dry ice factories, wartime brownstones, shotgun shacks. Byrne's lyricism is usually never content to celebrate love between people; it's a celebration of love between people and structures. Notably, the way structures and spaces influence relationships isn't a tract in an out-of-print textbook but a danceable groove.

In tracks "Don't Worry About the Government", "Cities", and "Strange Overtones", Byrne explores the buoyant (if misguided) expansionist mindset of late capitalism, the suburban isolation resulting from utopian mid-century urban planning, and the Great Recession-era social retrenching. "Don't Worry About the Government" places the joy of work and life firmly in the hands of expanding infrastructure; Byrne makes comparisons between civil servants and his loved ones, although his main focus is the inherent power of the building itself: "my building has every convenience / it’s gonna make life easy for me."

My building has every convenience

It's gonna make life easy for me

It's gonna be easy to get things done

I will relax alone with my loved ones

- “Don't Worry About the Government”, Talking Heads, Talking Heads: 77 (1977)

"Cities", meanwhile, is less satirical, more haunting. Here, a neurotic Byrne dips in and out of various cities, from London to Birmingham, trying to find the ideal mix of density, light, and culture. His take on Birmingham, with its largely empty houses and dry ice factory, is a portrait of a city lacking citizenry, a place that has been planned not to inspire culture but to eradicate it.

Lot of rich people in Birmingham

Lot of ghosts in a lot of houses

Look over there! Dry ice factory

Good place to get some thinking done

- "Cities", Talking Heads, Fear of Music (1979)

Meanwhile, "Strange Overtones" celebrates the seemingly unfashionable artistic impulse to create joy, even in circumstances of austerity. The subject of the song, a hapless singer who is overheard being joyous but not clever in the apartment next door, wants to reach out to "those standing out in the cold." The reference to an earlier era – "those beats are 20 years old" – underscores the notion of a far more vibrant time that is now considered unfashionable.

You're in the next apartment

I hear you singing over there

This groove is out of fashion

Those beats are 20 years old

I saw you lend a hand to

The ones out standing in the cold

- "Strange Overtones", David Byrne and Brian Eno, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (2008)

In 1986, Byrne took on the beautiful weirdness of late 20th century capitalism, making a film, True Stories, that is probably the most entertaining (and elegantly satirical) movie ever made about urban planning. Although films such as Koyaanisqatsi (1982) and Jacques Tati's Playtime (1967) had certainly explored similar themes, True Stories remains the most fun, cut to a lone white-collar worker dancing ecstatically in his knock-off Miesian glass boxed office.primarily because it works as a series of discrete music videos held together with tongue-in-cheek conceptual analysis and snippets of “city” life. In the film, property developer Earl Culver (played by Spalding Gray) gives a three-minute lecture about the changing nature of the economy by way of representative asparagus, lobster, and peppers at a dinner table. As Culver joyously hurls food into the air in a climax of exposition, we cut to a lone white-collar worker dancing ecstatically in his knock-off Miesian glass boxed office.

In another scene, our omnipresent cowboy-dud-wearing narrator Byrne takes us through a mall, a microprocessor assembly plant, and a housing tract while eerie, whispery music plays in the background. "It's an imaginary landscape, a place to raise your kids. Of course, nowadays, nobody's having kids, what with the end of the world coming up and all," Culver notes, before walking Byrne out into a bramble-strewn field. This idiosyncratic survey of a vintage middle class American outlook has become a historical gem, perfect for schoolkids curious about why the 20th century ended up the way it did. The movie merrily foreshadows trends in the U.S.’s next century, when a "career" would no longer entail a lifetime with one employer, and people would, on average, if at all, start marrying later and have fewer children. From an urban planning standpoint, this has accompanied a resurgence of the urban core as desirable real estate, as opposed to the tumble-weed environs of suburbia. True Stories depicts a reality that, ordinarily, would have been lumped into a series of spreadsheets and bar graphs, but in Byrne’s vision, is both joyous and animated.

In his 2009 book The Bicycle Diaries, Byrne pedals though numerous metropolises around the world including Berlin, Buenos Aires and Los Angeles, noting their relative accessibility, infrastructure, and cultural health. It's a real-life extension of his quasi tour-guide role in True Stories, but this time he's openly obsessed with the harmful nature of outdated planning thinking. In his role as pedestrian, Byrne contextualizes seemingly overwhelming issues for people who haven't endured an urban planning 101 course. Explaining that most U.S. cities are not very bike-friendly, Byrne says: "Lives, city planning, budgets, and time are all focused Economics is revealed in shop fronts and history in doorframesaround the automobile...How did it get this way? Maybe we can blame Le Corbusier for his 'visionary' Radiant City proposals in the early part of the last century." He goes on, "I also believe that a visitor staying briefly can read the details, the specifics made visible, and then the larger picture, and the city's hidden agendas emerge almost by themselves. Economics is revealed in shop fronts and history in doorframes. Oddly, as the microscope moves in for a closer look, the perspective widens at the same time." His thoughtful approach to what could have been a mildly amusing travelogue transforms the book into both a historical document and a larger global question: What kind of cities do we want in our future? Like an upbeat Jane Jacobs, Byrne seems to say that while we can't pretend we haven't made mistakes, we can learn to better identify them, and become more critical users of our cities.

Byrne continued to explore space and the impact it has on culture with his highly accessible 2010 TED Talk, "How Architecture Helped Music Evolve," in which he traced the development of music composition as dependent on its intended venue. He argues that the arpeggios of Bach would have been vastly different had they not been performed inside an 18th century cathedral, but instead in the acoustically flat, packed room of CBGB, where Talking Heads first began performing in the late 1970s. He sees similar developments in nature, noting that bird songs change depending on the acoustics of their specific habitat. This observation takes composing music out of the vacuum-space context of one's own head, and places it firmly into the shared space of performance. Essentially, Byrne's thesis is that the physical world shapes and changes how the creative impulse manifests itself. Musicians are, in some respect, always subtly embedding the architecture of their times within their music.

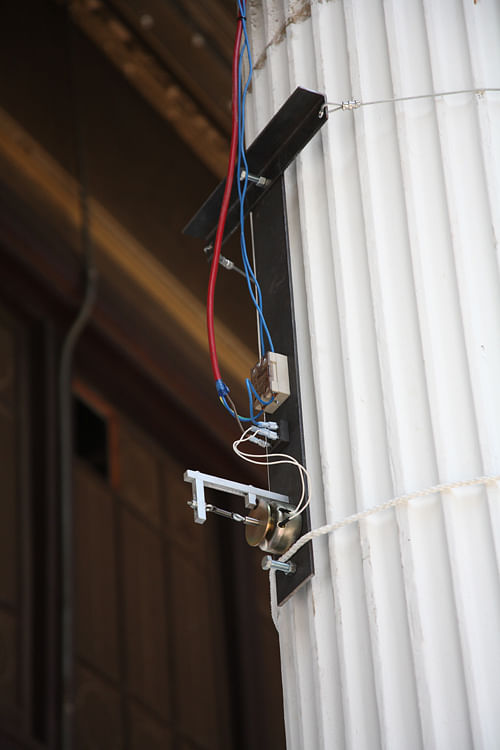

Byrne took this concept in a very literal direction with his installation "Playing the Building”. The equivalent of a brick and mortar organ, with fluted utility pipes, basso electrical boxes, and a series of mid-tonal steel columns, the piece debuted in Sweden in 2005 and eventually transformed three additional sites into working instruments, including the Battery Maritime Building in New York City. Each key on a traditional organ was rigged to "play" a particular part of the building, triggering rods that tapped girders or electrical currents that powered HVAC equipment. Byrne did not write a specific musical piece for any of the buildings, preferring instead to invite people to play the organ and experiment with the resulting cascade of sounds. On one level, people would experience the materiality and acoustics of the buildings in an unprecedented way. Who, after all, actively considers the musical key of the ceiling fan, or the timbre of the water pipes?

Who, after all, actively considers the musical key of the ceiling fan, or the timbre of the water pipes?Individually working their way through a symphony of materials, visitors to the installation would ultimately create their own work of art. This act is, perhaps, the most tangible manifestation of Byrne's contribution. From Vitruvius to Koolhaas, architects have adopted any variety of ways to convey the magnificently complex scope of their discipline, often resorting to ever denser, more abstract texts and frenzied infographics. Byrne made it possible for someone off the street to sit down at a piano and start getting it immediately. By being as much a creator as he is an enthusiast, Byrne has placed the beauty of architecture and infrastructure into the pop cultural lexicon. It's a good place to get some thinking done.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

10 Comments

Somehow his particular kind of interest in Architecture and Urbanism seems of the 1990s/early 2000s to me. Like an early hipster's take on the poetics of urban rusticity, it seems to have a lot to do with the aesthetics of a homespun, DIY, patchwork lifestyle. Now that we're in 2015, and huge sections of NYC are gentrified to the point of being unaffordable to middle and lower income people, the image of an affluent culturally aware rock star bicycling through Brooklyn seems less innocuous today than maybe it would have in 1995 or even 2005.

To understand a piece of 'audio', time is required.

Visual items can be grasped in split seconds, or practically no time at all and then abstracted to ad absurdum - as pointed out in the essay above...and put into spreadsheets easily.

A while ago I read this random bit of text by David Byrne in "Songs without Rhyme" where he talks about a world of genetic engineering that looks very much like the world of 2015 Virtual Reality....which made me think of the this text -

Do you like the Talking Heads, yes or no?

davvid - the only way I understand your statement above in this context is as follows:

Somewhere in the 90's a few people could forecast what was coming or what we were about to fall out of historically and never return to - Space, Time, and Architecture so to speak.... My quick list is: Jean Baudrillard, Paul Virillio via Ctheory, Marc Auge, beyond Byrne and Coupland referenced above and more related to 'typical architectural theory'.

I was in high school in the 90's, so I remember just enough and found Ctheory.com freshman or sophomore year of college (97-99) which was kind of taking the pulse of the birth of what we are into now in 2015. I have no reason to 'regress' back to this 90's stuff other than the initial observations of what was to come are pretty accurate and having lived that era a bit, I can vaguely remember what is really missing these days....

Julia's piece on Byrne points to something, at least the way I read it via David Byrne, points to something that is a possibility only through an actual encounter with 'time' specific to a 'space', an actual encounter with 'architecture'....see "Playing the Building"....not a flip book of eye candy stills....(Space, Time, and Music in Architecture)

"Who, after all, actively considers the musical key of the ceiling fan, or the timbre of the water pipes?"

Byrne was too smart to be architect, and his view is both nostalgic and futuristic.

most of these lyrics were written before i ever attended architecture school and that was a very long time ago. i read a similar essay about byrne and architecture around the time True Stories came out. fa fa fafa fa fa fafa fa fa.

wonder what David Byrne would think about that Google project.

Inspired by this piece a week or two ago, I went to my local Video Rodeo and rented True Stories. Quite fun. Understated and more "celebration", than irony or snark.

It also has that simply BONKERS mall fashion show and the FANTASTIC ‘People Like Us‘, closer, sung by John Goodman.

Nam, I checked out Netflix and Vudu and no luck on this flick, but youtube had the John Goodman bit...

Any other way I can get this video....library maybe?

What about Amazon Instant Video? Not sure about where you love, but Video Rodeo is a indie video rental store. You got any of those?

that should read "live"...

Julia and Nam, that was a hilarious flick (via Amazon) and very observant on Byrne's part about 'modern' architecture - the pre-fab metal building was the outcome of 'modernism' (been saying that for years, ha)....read Generation X a few weeks ago, nice little follow-up flick...

so I'm still wondering now that the cpu/programs = phone/apps are so user friendly if there is any difference between the following, besides 'speed'-

vs

or

isn't this just as active

as

other than originally based on 'privileged' invites and a mass source for advertisers to determine demographics for their marketiing...what's the difference between

and this amazing money maker!

seems like we're cycling, just faster? time is running out, no time left, less time, forget time, time takes too long?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.