Working out of the Box is a series of features presenting architects who have applied their architecture backgrounds to alternative career paths.

Are you an architect working out of the box? Do you know of someone that has changed careers and has an interesting story to share? If you would like to suggest an (ex-)architect, please send us a message.

Archinect: Where did you study architecture?

Igor Siddiqui: I received my Bachelor of Architecture degree from Tulane in New Orleans, followed by graduate studies at Yale. Tulane School of Architecture was a particularly exciting place in the mid-90’s, with Donna Robertson as the school’s visionary dean. Dean Robertson brought so many incredible architects, academics and thinkers to the school, from lectures by Rem Koolhaas, Barbara Kruger and the whole Assemblage crew to the designers and educators who were just beginning to emerge, like Michelle Fornabai, Ila Berman and Cathrine Veikos. It was such an awesome entry into architecture culture and a rich foundational experience. Many of the people from that era remain present in my life, from the mentors whose advice I still often seek to my former classmates who are out there doing incredible things. A few years later, after some exposure to practice, I decided to pursue graduate work and go to Yale, partially because of the architecture school’s adjacency to and crossover with the art school, which at the time seemed like a priority. I made videos, worked on enormous urban projects, became much more involved with digital media during this time, and also started thinking more explicitly about how I wanted to practice.

At what point in your life did you decide to pursue architecture?

IS: Signing up to study architecture when you are eighteen years old is such a gamble. I knew so little about it, but it seemed like a slightly saner version of art school. I am not sure that I ever found sanity in architecture school, but what I did very quickly discover was the rigor of thinking and making, the incessant questioning of givens, and endless potential for meaningful engagement and contribution. In a way, the architecture curriculum served as a gateway to so many other things like theory, philosophy, art. Thinking about conventional practice seemed somewhat irrelevant during those years and it wasn’t until perhaps my third or fourth year of school that I started seriously considering an actual career in architecture. My first job after school was at a large firm in New York, a thrilling experience in some ways, but one that was ultimately not all that interesting to me. After this brief corporate stint, I landed a position at 1100 Architect, where I stayed for several years. I could really relate to the scale, sensibility and obsessive attention to detail in the work and I also enjoyed the studio’s expanded view of architectural practice. I worked on everything from furniture pieces and collaborations with artists to buildings and urban proposals. Although the firm’s earlier work is often associated with beautiful interiors, it was there that I actually extensively worked on a number of new ground-up building projects and got to see them all the way through from design to construction. So many 1100 alumni went on to start their own successful studios and this seemed like a viable career trajectory.

When did you decide to stop pursuing architecture? Why?

IS: For me it’s been more about expanding what I do with architecture rather than breaking from it. In an interesting way this has led to the development of expertise in the design of products and interior spaces. When I started my practice in 2006, most of the projects that we were working on were at the scale of objects, interiors and small buildings, and that set a certain kind of tone for the practice. It was also around this time that I also started teaching, first as a digital media instructor and later as studio faculty in several different architecture programs in New York, Philadelphia and San Francisco.

Eventually I found myself effectively having a full-time teaching schedule, but also wanting to ensure that there was always a strong connection between how I was practicing and what I was teaching. When a few unsolicited opportunities for teaching outside of traditional architectural programs came up, I realized that my work resonated most strongly around the soft edges of architecture and in relation to certain kinds of interdisciplinary design practice. Architects are generalists, but I have found it helpful to be framed by the institutions where I have taught in terms of specialization and expertise. It has made me focus on certain aspects of my work and develop them more fully as well as provided me with exciting opportunities to contribute to specific areas of discourse in design. Writing has become an increasingly important part of my work.

Describe your current profession.

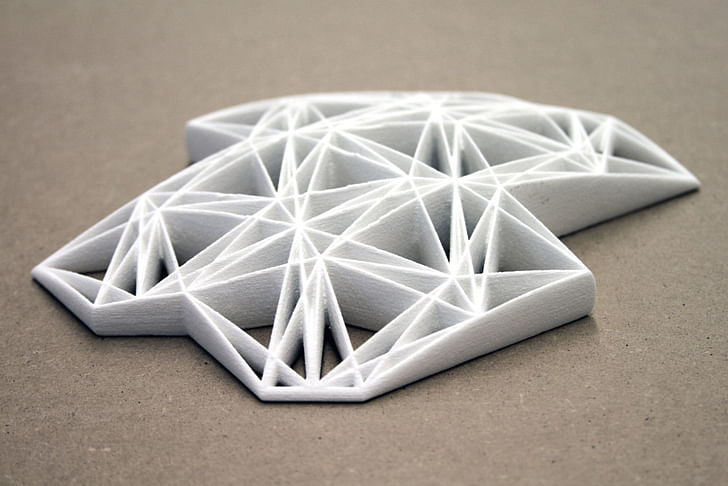

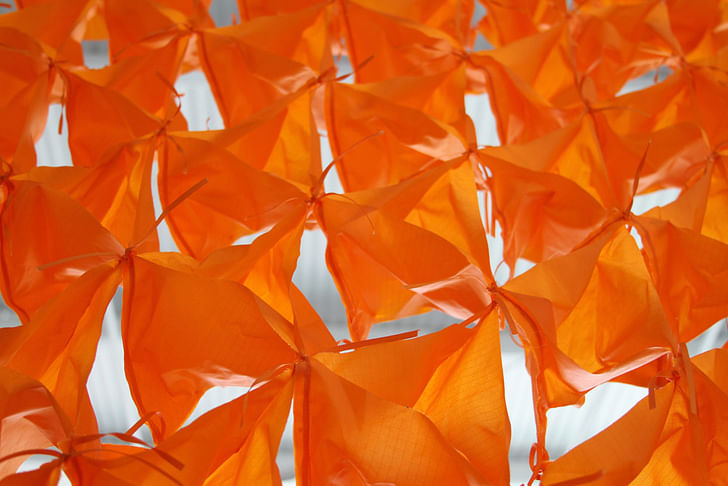

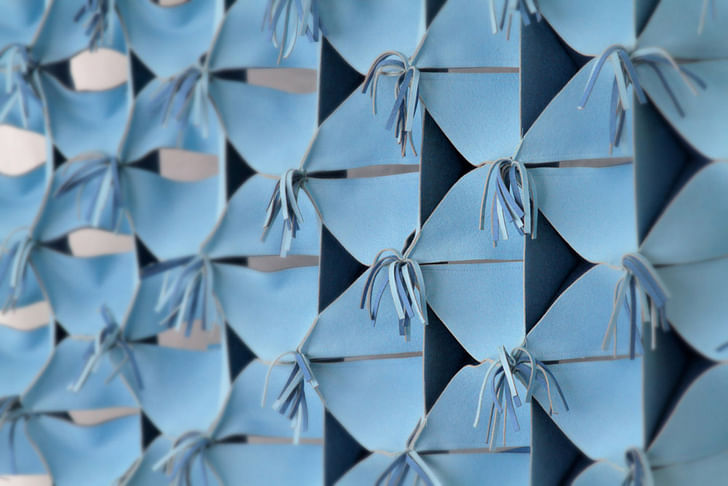

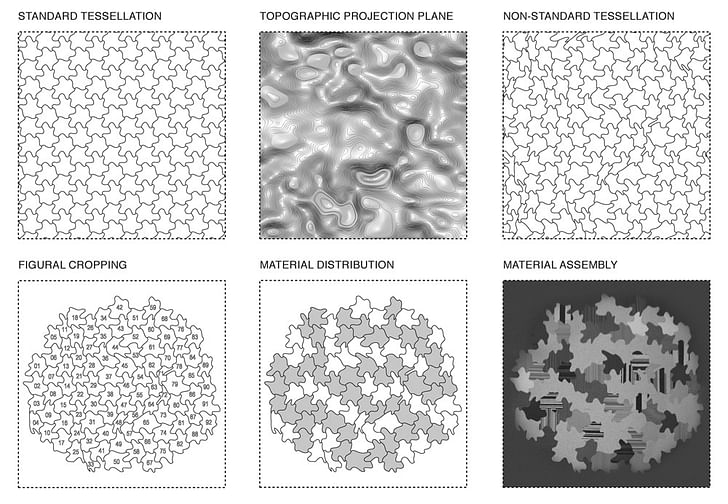

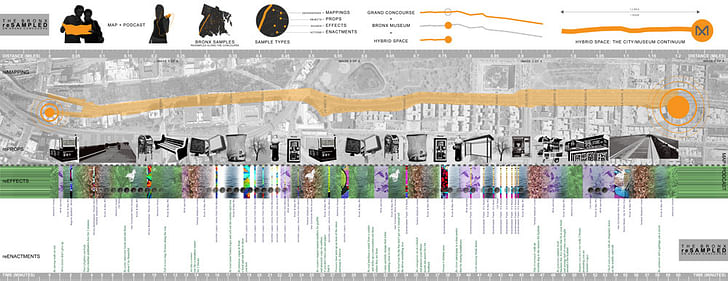

IS: I am the principal of ISSSStudio and an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Architecture. ISSSStudio was formed in Brooklyn with Susan Sloan as its original co-founder. Susan has since started her own successful practice, and I now spend most of my time in Austin. Majority of the work that the studio is currently doing is either in New York or California, and includes everything from product prototypes to single-family houses. At UT, I teach courses in both architecture and interior design programs, from foundational design studios and core digital media courses to advanced fabrication seminars. One of the many amazing things about the school is that it has several different programs under one roof without any departmental separation, encouraging and facilitating exchanges, overlaps and collaborations across disciplines. At this moment, in both practice and teaching, my work primarily considers the contemporary interior as a framework for encounters between manufactured products and architectural spaces, and through it I have been investigating digital design techniques, fabrication technologies, material properties, as well as issues of flexibility, mobility and part-to-whole aggregations.

What skills did you gain from architecture school, or working in the architecture industry, that have contributed to your success in your current career?

IS: One of the things that architects know how to do is to adapt to changing conditions while maintaining a long view of their creative trajectory. This I think differentiates architecture from both other kinds of artistic pursuits as well as from most other service-based industries. I think that both of these things matter equally, but balancing them is a continuous challenge. In terms of my own architectural education, I perhaps gained the most from explorations that were at their most hyperbolic, meaning that one was encouraged to turn up the volume and intensity of both concept and action in order to investigate various conditions at their extremes. This teaches one how to generate design thinking that is robust, innovative, impactful, even polemical. Through practice, on the other hand, I learned the importance of considering the economy of conceptual and material means. In the end, the hyperbolic and the economical are not mutually exclusive, but rather codependent. One allows you to generate, the other to edit.

Do you have an interest in returning to architecture?

IS: Well, one could say that what makes one’s work architecture is the designer’s disciplined thinking and process and not to the specific scale, typology or medium of a project. If this were true, I’d say that there is no return to speak of – I’ve never gone anywhere. However, I do think that my relationship to conventional architectural practice has been transformed and my sensibility about space-making expanded. First, I would say that I am increasingly interested in ways of defining space through means other than the introduction of new architectural volumes, focusing instead on imaginative re-tailoring of existing structures, performance-driven surface manipulations, exploiting relationships between objects and occupants, and taking advantage of ephemeral aspects of spatial experiences such as light, sound and smell. Second, by focusing on fabrication and product design, my work is at least as concerned with factory production of designed artifacts, as it is with site-specific construction. And finally, while ISSSStudio continues to take on projects where we have the principal role of coordinating the overall project - typically up to the scale of single-family houses - I am more and more open to working on projects in the capacity of a consultant – the way an engineer or lighting designer would, where we get to apply our expertise to a certain piece or layer of a larger project. This shift in mentality for me has been the greatest shift away from the way that I have been trained to practice. It is the “not everything” approach: rather than aspiring to shape and solely coordinate the big picture, it is a about a specific contribution to a larger or thicker whole. This is the direction that I will likely continue to explore, and one that in my mind suits the increasing demand for collaboration in design.

Learn more about ISSSStudio at www.isssstudio.com

2 Comments

Great work, Igor!

very inspiring work sir.....

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.