Visitors to Greene and Greene's Gamble House in Pasadena, California, that imposing emblem of the American arts and crafts movement, are warned beforehand not to wear high-heeled shoes. The pressure of the heels could stress the carpets, aging them out of their prime over the course of daily tours. This past October, artist Asher Hartman visited the what is, in fact, being preserved? Is artistic intervention capable of affecting the physical structure's nature?Gamble House (presumably not in high-heels) to perform a psychic reading, communing with its foregone spirits in wood and flora. Hartman's reading was an outright performance, harnessing the House's historical status to riff on emotional and spiritual potentials. His piece is based (in part) on the House's history, preserved by footwear restrictions and velvet ropes, but pulls on alternate realities for the space – the indigenous people native to the area, children running in the yard, the domestic help. His reading of the House changes its status, and puts into question what is, in fact, being preserved? Is artistic intervention capable of affecting the physical structure's nature?

This question formed the basis for the two-day "Intervention" conference, taking place this past October in three of Los Angeles' historic modernist homes. Subtitled "Contemporary Artists and the Modern House", the conference grappled with the changing trends around modern architecture preservationism, in regards to how experimental art installations within the houses recast the structures' identities (both historic and domestic). This discussion makes quick reference to surrealist methods of juxtaposition and intuition, and how these impressions match up against the static, preserved, presumably hallowed homes. Asher Hartman's performance, part of the Machine Project Field Guide to the Gamble House, was loosely associated with Intervention, which took place (in parts) in Rudolph Schindler's Kings Road House, Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock House, and Richard Neutra's VDL House.

The conference was motivated, in part, by "Competing Utopias", a preceding exhibition held at the Neutra VDL House that furnished the home’s interiors entirely with Cold War-era objects originally from within the Eastern Bloc. Scenes were set in each room with the precision of a set designer, depicting the life of an East German family right down to the children's toys littering the floor (Dora Epstein Jones, theorist and professor of architectural culture, likened the installation to non-narrative film). The exhibition ran for two months, during which visitors to the VDL could continue touring the home as per usual, but with the added dimension of an alternate utopian vision; Soviet communism overlaying American (by way of Vienna) modernism.

As noted by the curators Sarah Lorenzen, David Hartwell, Bill Ferehawk, Justin Jampol, and Patrick Mansfield, this added dimension wasn't always properly interpreted. Some tourist took the intervention as a face-value historical replication, depicting the little-known time Neutra spent in East Berlin. Others conjectured on Neutra's personal political beliefs, interpreting the the idea of visiting a historic home and seeing a fantastical supposition would be irreverent, or almost profaneintervention as an "outing" of the architect's pinko-leanings. But what's fascinating about the misinterpretations is that they insist on seeing the intervention as reality. It's as if the idea of visiting a historic home and seeing a fantastical supposition would be irreverent, or almost profane, rather than artistic, so the viewer does whatever set of mental gymnastics to reconcile the two worlds. Anthony Carfello, programs manager at the MAK Center, testified to this, in regards to one of the Center's prior exhibitions linking Schindler to the Black Dahlia murder. And despite being clearly built on rank conspiracy, the link turned out to be difficult to break in the minds of some visitors, thanks to the context of the Center's authoritative presence.

For pilgrims to historic homes, the desire to reconcile experience with historical accuracy can overwhelm imagination and impressionism. This is largely due to the fact that, after a piece of architecture becomes monumentalized for its historical or aesthetic prominence, visitors come to experience its role in a greater piece of fiction – the folklore of whatever the curatorial narrative d'jour has deemed necessary, regardless of its absurdism. This informs the initiative behind the 1975 restoration project for the Acropolis, which aims to rebuild the significantly decayed and destroyed structures (due to modern and ancient incidents) using original stone, collected in fragments from around the site. Most likely, this reversion is to a time and significance deemed most significant and effective for tourism.

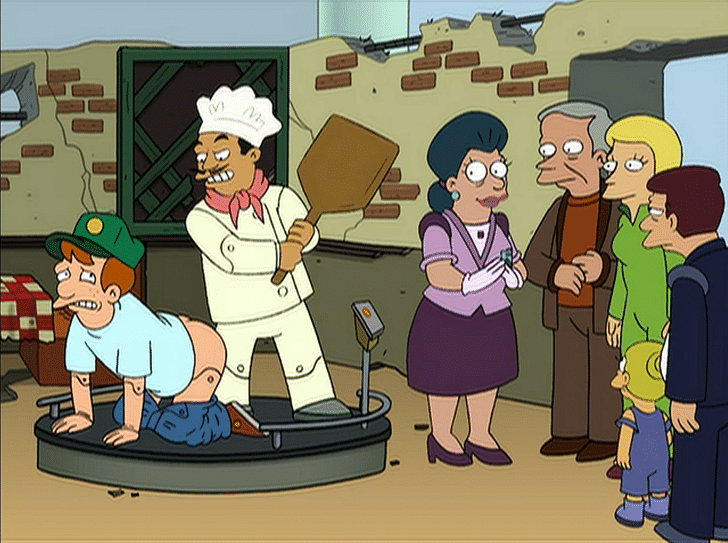

This practice is made more absurd when projected into an imagined future. The "Jurassic Bark" episode of the show Futurama, which takes place in the year 3000's New New York, features an exhibition at the Natural History Museum of an authentic 20th century pizza parlor. The pizzeria happens to be the one where Fry, the show's protagonist, used to work – before he accidentally cryogenically froze himself to end up in the 30th century – and he takes issue with a tour guide's interpretation of an artifact found at the scene: a wooden pizza peel. The tour guide claims the paddle was used to "gently discipline" delivery boys, but Fry objects, saying the paddle was also used to "move pizzas and crush rats". A silly example for sure, but quite apt – future historical interpretations, whether aesthetic or anthropological, must pick and choose which elements to persist and obscure.

The problems with this synecdoch-ial method come alive in the present time with things like façadism, prioritizing superficial qualities as representative of three-dimensional spaces. As in the case of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien's American Folk Art Museum, where the façade was placed in storage as the rest was demolished, façadism does little to convey the significance the Villa Savoye must become a kind of sitcom set-piece version of itself; an inflated icon of dressed-up authenticity, perpetuated to "institutionalize culture"of the actual space, and seems like more of a concession to the demolition's opponents than a triumph of curation. In the case of an “integrated juxtaposition” style of preservation, which Competing Manifestos subscribes to, the statement is bold but risks being easily missed, invisible to those passing through with the wrong glasses on. With more explicit interventions, where the objective difference between architectural preservation and art installation is more obvious, the dynamic can be more improvisational; that of partners playing off one another. This style of preservation could even suggest an additive process, where new structures are built in a style that is at once contemporary, reverential and harmonious to the original's context.

One such purposeful juxtaposition is the artist Santiago Borja's "Sitio" project at Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye. As discussed at the Intervention conference, the project takes three forms: two "palapas" (a shelter made from palm fronds) are installed on the grounds; "tapis" (rugs) are placed inside; a woven "suspendue" ceiling covers the terrace. Each intervening object has a root in traditional Mayan artisanship, and Borja has his own thesis as to why he chose these objects in particular, related to a reputable interpretation of the structure's pilotis as derived from a child's fantasy. At the Intervention conference, Borja framed Sitio in conversation with writer and critic Mimi Zeiger as commentary on the tourism industry, and how institutionalized cultures will shave and mold the original structure's existence into whatever object is most palatable within that touristic, architectural narrative. Borja argued that, for the sake of the touring public's eye, the Villa Savoye must become a kind of sitcom set-piece version of itself; an inflated icon of dressed-up authenticity, perpetuated to "institutionalize culture". Borja's Sitio tries to combat that, inserting objects incompatible to the Villa's time and place, casting it in sharper relief.

In the end, nearly all complications of architectural preservation hinge on a what is effectively a time travel paradox. Preservation is opposed to passing time; it attempts to deny the existence of a changing world around it, and adheres to its curator's chosen historical epoch. But when anyone, for this case an artist, comes in and tries to re-engage with that preservation, they are effectively coming from the future, from the perspective of the building. future interlopers and past historicism sitting together at the dinner table.So what happens if that interlocutor creates such a splash in the preserved building's history, such that the structure becomes better known for that artistic intervention than for that status in which it was initially preserved? Is it suddenly the curator's responsibility to include that intervention in their future preservations?

This essentially creates a paradox of timed preservation, where if the intent is to keep something in its state of highest significance, then that may include multiple spaces in time – future interlopers and past historicism sitting together at the dinner table. In the light of these interventions, a preserved space may have to be completely re-imagined with the currents of the intervening tide, collapsing dimensions of past and present as necessary. Preservation is living history, and with any life, it has to die.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

8 Comments

"Preservation is opposed to passing time; it attempts to deny the existence of a changing world around it, and adheres to its curator's chosen historical epoch. But when anyone, for this case an artist, comes in and tries to re-engage with that preservation, they are effectively coming from the future, from the perspective of the building. So what happens if that interlocutor creates such a splash in the preserved building's history, such that the structure becomes better known for that artistic intervention than for that status in which it was initially preserved? Is it suddenly the curator's responsibility to include that intervention in their future preservations?"

I love this passage so much.

pres•er•va•tion (ˌprɛz ərˈveɪ ʃən)

n.

1. the act or process of preserving.

2. the state of being preserved.

When I think of preservation, my mind almost immediately is drawn to formaldehyde, why?

It seems to me that the very nature of preservation is inherently anti-humanist. People live, and lived, in these homes, perhaps many different families, and at the end of the day, aren't these the real performance artists? Ultimately it's the people that live in these spaces that create memories, interventions, that are better known than the architecture. Architecture, at the end of the day, only matters to architects and the cultural elites, and when the architecture is long and gone, it's the memories that remain.

I think you're over thinking things a bit. People preserve things that they hold dear all the time. I try to preserve my marriage or my kid's drawings or whatever, not to stop the passage of time but becasue I like those things. In our disposable culture the idea of constantly re-doing everything becasue of an obsession with the new seems irresponsible. And if you think that architecture only matters to architects or the cultural elites, you should read the sociologist reports on those communities bulldozed by Robert Moses to build the cross Bronx expressway.

"Preservation is living history, and with any life, it has to die."

It sounds poetic, but it's not that simple. If you zoom out and see life beyond an organism, you would see that death isn't the end of life but part of it. Some things in life should die, but those that are beneficial to humanity should be preserved. It reminds me of the difference between evolution and revolution. A revolution kills what was in favor of something new while evolution allows certain things to go on living in differing forms. There are times for one and times for the other, not that we all need to agree on them. The modernists where hoping for a revolution that erased history, but as we can see from Architect, we are in the midsts of a modernist revival. I think they call it mid-century.

Revolution has a youthful romanticism that I don't begrudge anyone, but evolution starts to look more appealing as one ages becasue we find some things are worth preserving. Plus, if you constantly tore down what civilizations produced, how would we evolve?

Maybe Amelia should compare the well-preserved Gamble house with Greene and Greene's Thorsen House, currently occupied by Berkeley's Sigma Phi Society. The entire fraternity lives in the house, which is in somewhat less than ideal condition.

They give tours by appointment, well worth it.

Miles, I used to live in Berkeley, a couple blocks from the Thorsen House. I lived in a 1911 Julia Morgan mansion, owned by UC Berkeley's student housing cooperative, who had purchased it from a now-defunct sorority. The house is stunning, with a remarkable three-story brick staircase leading up the front, part of its original Mediterranean style. In 1957, when the struggling sorority still owned the property, they renovated it to accommodate more housing and look more "modern".

I often wondered what it would have been like to live in that house had it been kept in its original condition (Morgan certainly didn't imagine co-op kids throwing house parties there) but what I ultimately loved was how you could read the history of the building, the University, and the city in its renovations. The house is recognizably still a Morgan, but with elements of dingbats and flourishing veganism.

Thayer, I find your examples interesting, and problematic, partly because I think you're under thinking them. We preserve those images, my mother does, photo albums, etc, precisely because they freeze time. We long for those nostalgic moments, those times when the world was perfect, albeit many times in the eye of the beholder. I mean I'm divorced, and I still have my wedding album, why? Because they preserved for me a happy time in my life, a life filled with promise. I know, it's a flaw, but it's still nostalgia.

When I refer to architecture, I mean Architecture, capital A. Most people don't care, the memories are what matters. My grandmother's home, barely remember it, but I remember the red and white checkered linoleum, the smell of sauce, the holidays, her dying. That's why I carry, the life inside the container.

Evolution is cruel, traces of the old remain, but they many times become useless in the new world. I mean, why do we have an appendix anyway? I believe we needed at one time, but no longer need it, and I have zero longing for it, especially if it serves no use.

b3tadine,

We differ in one crucial respect on this point. I don't think you holding on to those photos of your wedding album is a flaw. I also don't think there's anything wrong with nostalgia, at least in moderation. Sometimes, a function isn't as concrete as taking a dump or keeping out the cold. Sometimes it's a poetic longing as important as the life span of roof shingles, if not more. Life is hard (as you say) and sometimes we need a respite in whatever form we find. Just as some might say neo-gothic building is a sham becasue it's trying to make us believe it is a medieval building, not at all. While not my stylistic preference, who the hell would think something so stupid? No, it just might be a vehicle to elicit a pleasant reaction from a romantic and beautiful composition, or simply a contextual decision. Like you holding on to photos, pleasure is a relief to the saddness that pervades us at times.

If you believe the ads, just about any mood that isn't celebratory or in repose is an abberation. This does us (as a species) no favors. Nowadays, if a kid can't sit still, he's labeled a freak. Or if you aren't always smiling, your 'depressed'. Not to dismiss the real suffering of those with clinical depression (like my mother had) sometimes you just get a case of the blues. Have one or two drinks, or go chop wood or whatever helps. And if you want to look at an old photo to make you smile, go for it. Don't seal your heart away becasue of some ideal vision of an ubermensch.

For example, my mother became seriously catholic after she suffered her first psychotic episode. Now, I'm an athiest, so you would think this would be problematic. Not at all. Esspecially once I realized what a balm it was for her to believe in something that gave her mind structure. Now that's an extreme example, but I mean it to point out that what is considered weakness by some is simply human nature in all it's glorious imperfection.

So back to preservation. This idea that it's about preserving a view of history that was much dirtier in reality is as divorced from reality as those critics claim of preservationists. They simply want to hold on to something that makes them feel good or they feel serves as a memory of something worth remembering. Afterall, how many of us have had bad experiences intertwined with good ones. Yet for whatever reason, we tend to hold on to the good memories. I've read it's a mechanism of the evolutionary growth of our minds, but eitherway, it seems to be a survival instinct. If not, we'd be eaten alive by bitterness and cynicism, which in turn shut's out the good of the present, exactly what we need to feel whole again.

Nowadays, we're talking about preserving mid-century modernism. Again, not my personal preference, but I can see the optimism and romanticism in technologie's power inherent in some of those pieces. By all means some should be saved and preserved to illustrate our story and to serve as inspiration for the future. Afterall, what are we but a collection of stories that we tell others for them to understand us.

Ideally, I'd like to see the more organic preservation that Amelia eludes to in her story about living in Berkely, but as you might know, many builders find it cheaper to scrape and build a new. Labor is now expensive where as traditionally it was the cheapest part of building. That's a good thing for workers but bad environmentally. I guess one can't have it all.

Another aspect to preservation is that of preserving an example of the way things were done. Maybe Greene and Greene is not a good example of this per se (even though you would be hard pressed to build such quality today), but there was a time when things were done for a reason other than money. To some extent the history of modern architecture has been one of moving away from designs that evolved over time in response to local climate and materials towards active technology intended to replace the functions once provided by indigenous construction.

The Japanese rebuild all the buildings at Ise every 20 years. This is a tradition that keeps the craft alive, and with it the traditional crafts necessary to do so, specifically woodworking. In the meantime just try to find a watchmaker, or get a pair of shoes resoled. The Mercer Museum is Doylestown is a wonderful place to see some of the craft traditions erased by the industrial revolution.

There are two sayings that apply here:

They don't build them like this anymore.

and

They don't build them like this anymore, thank doG.

When you take into consideration all of the Black Dahlia theories that have been submitted to date, the Schindler theory may actually be the most coherent theory to ever emerge...it's nothing to be fearful of...some will refuse to see it, but the evidence is clear that Schindler should remain a viable suspect in the case.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.