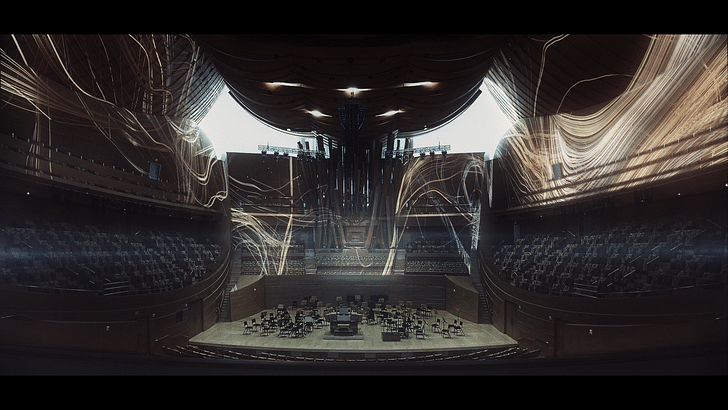

The billowing wood panels of the concert hall imploded before my eyes, as if physically ripped apart by the thundering crescendos of Edgard Varèse’s Amériques. One moment the massive organ was radically disfigured to the point of unrecognizability; the next, its forms re-emerged beneath the luminous, moving mesh mapped onto the structure by the artist Refik Anadol. For less than a half hour, the Walt Disney Concert Hall was transformed in an exhilarating synthesis of architecture, music and digital art: the first iteration of in/SIGHT, a series of ongoing collaborations between video artists and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, the performance was lively and entertaining. The progressive work of Varèse felt like a fitting partner for Anadol’s ambitious animation of Frank Gehry’s famous hall. Architecture can become a canvas. As Salonen threw directions at the orchestra, the wood-paneled space seemed to respond as well, as if tethered with fragile, invisible bonds to the furious motions of the conductor’s baton. The signature, discordant chords and swirling polyphonies of Amériques solidified into physicality through the magic spell of projection mapping. Or, conversely, it was the architecture that melted into music, as if liquefied under the impossible pressure of light. “Architecture can become a canvas,” Anadol told me over the phone.

But as the applause quieted and the lights returned, from behind me I heard a snide remark: “It’s like they just projected an iTunes visualizer.” The spell broke and, as I walked down the stairs of the concert hall, I also wondered if perhaps this was just a gimmick. After all, so-called classical music is in an assuredly sorry state. In the past few years, reports have emerged documenting significant declines in attendance at classical performances, sometimes with irrevocable consequences. Was the performance a musical equivalent of “jumping the shark”? For example, in 2013, the New York City Opera – the so-called “People’s Opera” – filed for bankruptcy. Sometimes it seems like orchestral music has become the butt of jokes or relegated to the realm of the old and white, wrapped up in the misleading nominal category of “classical”. Was this collaboration merely an attempt to drive up attendance for the LA Philharmonic through an injection of hipness in the form of digital art? Was the performance a musical equivalent of “jumping the shark”?

When Walt Disney Concert Hall was barely a wad of crumpled paper on Gehry’s desk, some critics vocally argued that he was unfit to design the building, that his designs were not dignified enough to house a world-class orchestra. (This was before his Bilbao museum launched him to world-fame and when he was known primarily as an experimental architect who elevated everyday materials like chain-link fencing and corrugated steel.) Actually, until Lillian Disney, the primary financier of the concert hall, stepped in, a Disney lawyer had told Gehry that the Disney name would never grace one of his buildings and there were attempts to force other architects into the project.

From its inception, Walt Disney Concert Hall has defied the norms of an music hall.

Of course, today, Walt Disney Concert Hall has become a defining landmark for a city that doesn’t have many, rivalled mainly by a series of letters left on a hill from an advertising campaign. One of the contributing factors for the Hall’s success is its many democratic design gestures. The interior hall has no stratifying suites or boxes, but rather seating circles the hall; in some seats and with binoculars, one can read the notes as the musicians play them. Unlike venues such as New York’s Lincoln Center that have grand open plazas, one walks directly from the sidewalk into the metal folds of the building. The gardens that circle the structure are open to the public, even without a ticket. From its inception, Walt Disney Concert Hall has defied the norms of an music hall.

No doubt partially because of the progressive qualities of its home, the Philharmonic has also become known for pioneering adventurous programming that pushes the boundaries of the concert music tradition. in/Sight is hardly the first time that the LA Philharmonic has ventured into experimental territory or partnered with artists outside of music, such as the architects Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel. As Anadol explained, Varèse was a fitting choice to continue this legacy. Actually, the composer is not what an untrained-ear (such as mine) would normally consider classical – his work builds heavily off of the Western tradition, and has influenced musicians from John Cage to Frank Zappa. In 1958, Varèse collaborated intensely with Le Corbusier on Poème électronique, an architectural, visual and musical composition set in the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. The 8-minute piece was carefully crafted to not only fit the unique sonic capabilities of the building but also to accompany an experimental film by the architect-cum-artist.

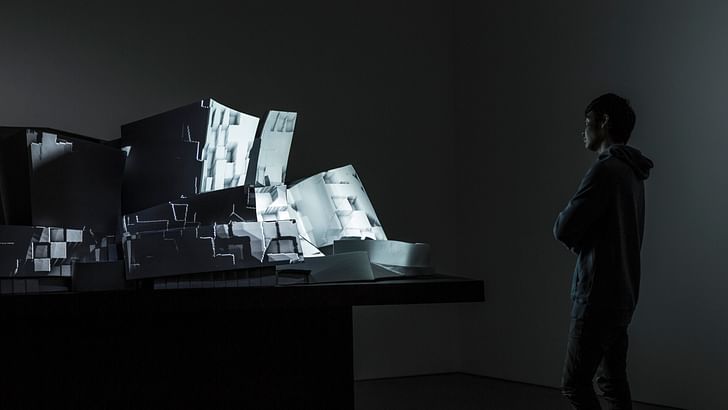

Continuing this collaborative tradition, Anadol worked extensively with architects in the creation of his installation. The project began while he was studying in the UCLA Design and Media Arts program, in particular under the tutelage of Casey Reas, an artist whose work blurs the boundaries between art, architecture and technology. This whole research process became the project itself. His initial proposal to the Philharmonic engaged the exterior of the building. As his research developed, Anadol was given the 3D models of the Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry and his team, an absolute necessity for the composition of his projections. At one point, Greg Lynn also became involved, offering Anadol advice and encouragement. Anadol explains, “This whole research process became the project itself.”

The projections utilized real-time mapping technology to map Salonen’s movements as he directed the orchestra. For Anadol, such advancements in technology not only create the opportunity for his work but also, in some way, demand it. “[The screen] is more than a century old type of presentation,” he explained. But right now, “we have the technology to make a type of story-telling using the existing space, itself.” Anadol’s project suggests the potential for a reimagining of how we experience not only music but also architecture. Architecture already operates through plays of light on form, but when light is harnessed by such technologies, shapes that once only suggested movement become viscerally animated, changing the architecture itself. The night was successful because none of the components – music, art, and architecture – felt subservient to another. Rather than a gimmick, the performance was an exciting example of how architecture can become more than its physical construction.

More precisely, the night was successful because none of the components – music, art, and architecture – felt subservient to another. Just like a symphony, each part worked together in harmony. I imagine that the concertgoer who denigrated the performance did so because they believed classical music should be contained within itself and its tradition. But in my opinion, this collaborative performance was a convincing showcase of the potential for technology to serve not as an embellishment to outmoded traditions, but rather as a partner in the construction of a bold, new aesthetic experience.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.