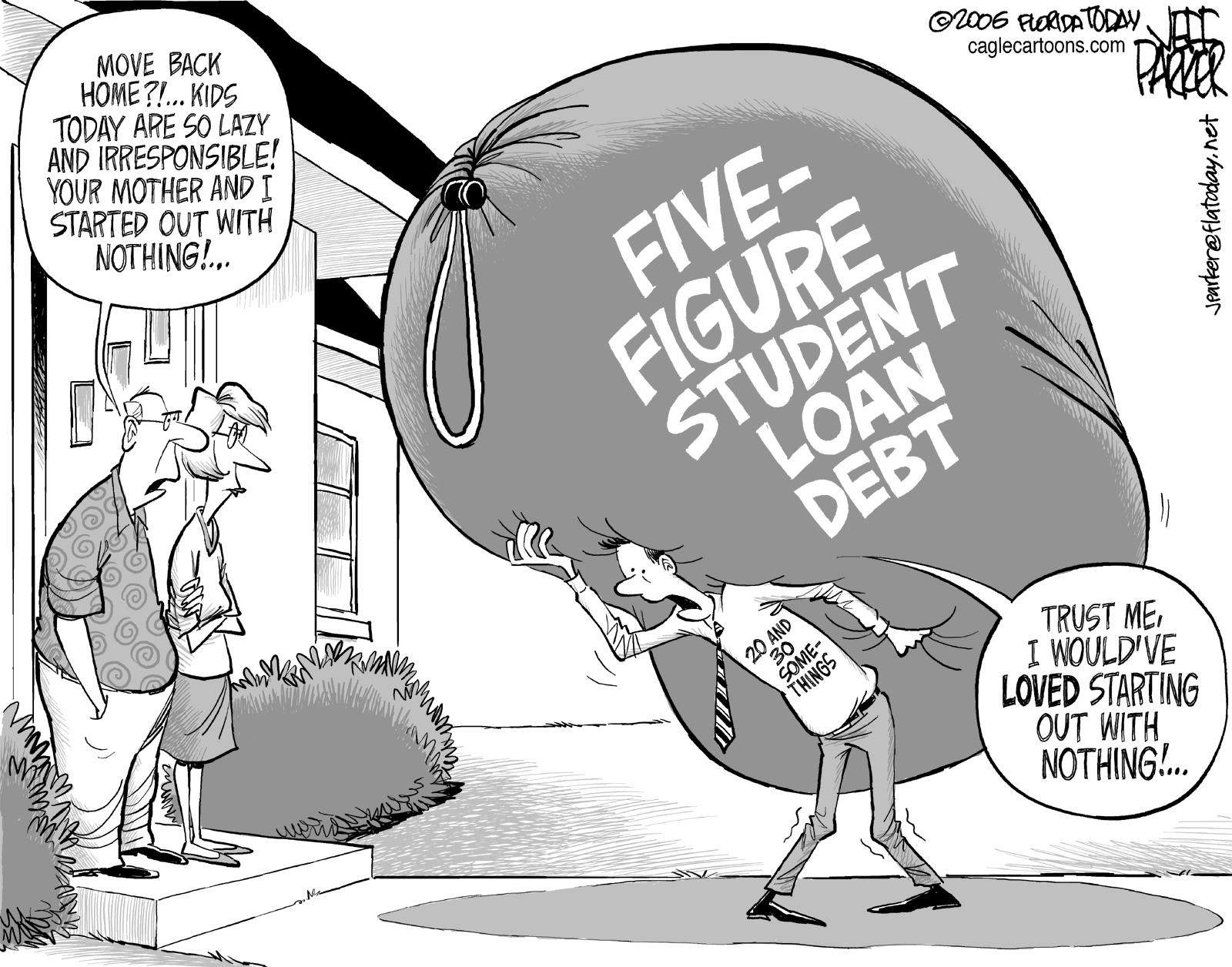

In the United States, around 40 million people currently hold student debt. This is a population that is greater than that of many countries. While, over the last 14 years, the average salary for young people has decreased by 10%, student debt has increased by nearly 500%. For most Americans, to become educated means to take on a relationship with banks that will last for years. But for young American architects the situation is even worse; the amount of schooling required to be able to practice professionally means taking on debt that you may be paying off for the rest of your life.

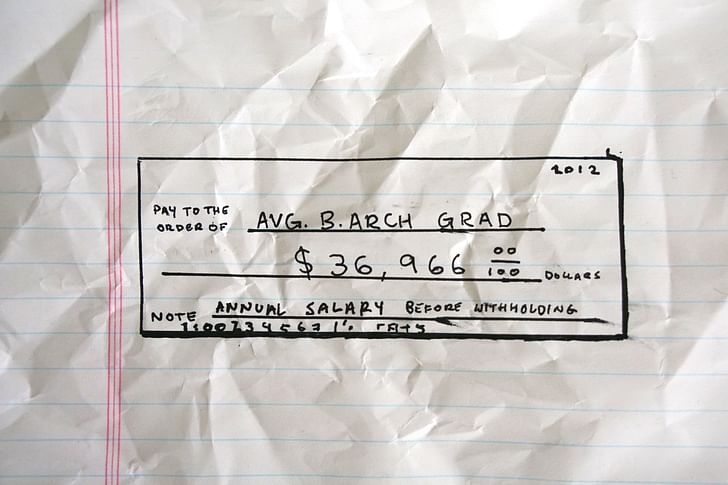

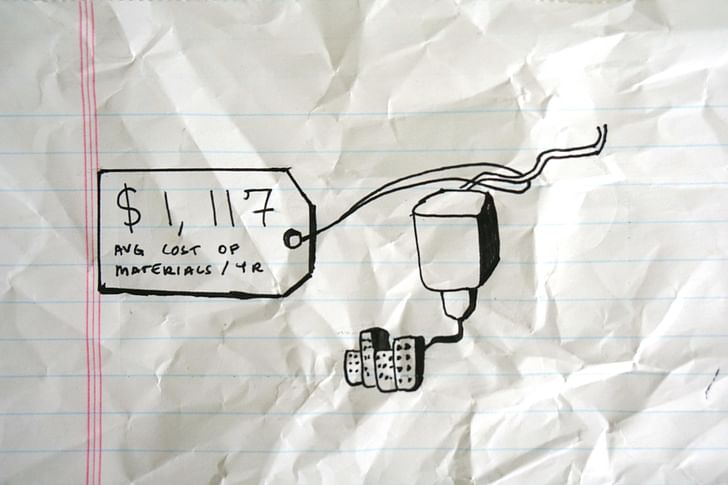

While the average student debt for a US American student is $29,400, according to a recent poll by the American Institute of Architecture Students, architecture students graduate with an average of $40,000 in loans. Not only does the profession require more time in school, architecture school is also a notoriously expensive academic experience. On average, an architecture student pays $1,117 annually on materials, which after being used to make a model are more often than not simply thrown away after crits (or in some cases, literally torn apart by a professor). Additionally, architecture students may be expected to pay for software licenses, computers, and, now, 3D prints.

Moreover, the professional field of architecture often puts extra burdens on its younger members, as if having to pay off monthly bills for the rest of one’s foreseeable future was not oppressive enough. A common cliche of architecture students is that they have so much work they have to sleep under their desks; they live and breathe their work. Meanwhile, students training in other fields are encouraged to take on part-time work to help alleviate their debt. Even medical students.

Some architecture firms may even solicit unpaid labor, often in the form of ‘internships.’ Like with other forms of exploitation, this has become a cycle perpetuated with the presumptive stance, “Since I did it, so should they.” Today, student debt is nothing short of a crisis. The problem with this logic, beyond being cruel and petty, is that it’s false. The issue is further convoluted by unclear labor laws and lack of effective regulation by architectural advisory boards. Student debt rises with tuitions, far outpacing salary increases. Couple that with changes to the global economy and a generally increasing cost of living, and the present strain of student debt stands in stark contrast to even a few decades ago. Today, it’s nothing short of a crisis.

Unless the situation changes, the current state of debt will inevitably have vast repercussions in the field of American architecture, particularly in contrast to counterparts in Europe, Canada and Asia where education is usually much cheaper, if not completely free (for example, Germany recently made all education completely free, even for international students). In an increasingly globalized field, architects trained outside of the United States simply have less to lose from experimenting with less financially-viable models. And experimentation is at the heart of architectural innovation.

Over the next few months, Archinect will gauge the price of becoming an architect today. Calling on an active community of architecture students (and some recent graduates), we sent out – and will continue to send out – anonymous questionnaires to learn about what its like to live with debt today. Statistics, while important, often obscure with averages and ignore those on the margins. Therefore, alongside numbers, we asked our respondents to open up about the lived experience of debt and the emotional responses it provokes. More often than not, those we interviewed admitted they tried not to think about their debt and rarely talked about it. But when they did they were often optimistic about their career choice despite the financial burden. For whatever reasons, the culture of today’s architecture community in the U.S. often places a taboo over frankly discussing debt. But debt is nothing to be shameful about; what is shameful is the propagation of the system that forces it upon young people.

As we continue this series, we would also like to use the space to showcase tips, strategies, and general ideas about how the architecture community can come together to change this situation. A good starting point is the AIA’s National Design Service Act Advocacy Tool Kit, which provides helpful information on legislative efforts to combat architecture student debt. If you have any other ideas, or know anyone who does, please let us know!

How old are you?

25

What's your nationality?

American

Where are you from?

Chicago, IL

Where are you currently enrolled and for what degree?

Graduated May 2014 with an M.Arch. II from Tulane University

What is your prior educational background?

BSAS from University of Illinois-Champaign Urbana

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No.

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation? Actual amount: $98,906.81

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

Undergraduate degree was financed by my parents with help from my grandparents and a scholarship (approx. $90k +living expenses), Master’s degree was financed myself and I received a scholarship ($32k total).

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

No.

Do you expect to be able to pay off your debt in the future? If so, when?

No, currently on the 25 year repayment plan with debt forgiveness.

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

It affects when I think I might retire, not necessarily trajectory.

[Debt] affects when I think I might retire, not necessarily trajectory.

Will your debt affect decisions like, for example, being in a smaller firm versus a more corporate firm?

Yes. I opted for a more corporate environment to ensure a competitive salary and benefits and being able to work as much over time as I want or need to.

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

I am open to alternate career paths but have not explored them and I cannot imagine having time or a life with a second job (and starting the ARE process).

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

I think about it frequently however try not to constantly worry or discuss with others. Discussing the mountain of debt does not make it any smaller.

Does your debt scare you? Keep you up at night? Do you ignore it? Broadly speaking, can you describe the emotions you experience when thinking about your debt?

Thinking about the amount of debt I have is completely overwhelming. It is such a large number to me that I cannot really comprehend it, much less imagine paying it off on an architecture salary. I consciously try not to think about it so I’m not worrying about something that I don’t feel I can change in the foreseeable future. It does not affect how I function (losing sleep, severe stress) and I try to still go out and have fun (which means spending money).

I will certainly not be encouraging my kids, or anyone that asks me, to go into architecture.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

I heard that architects “didn’t make a lot,” but being in high school wasn’t really aware what that meant (I had never had a budget or had to support myself, so what is a low salary?). I think architects are underpaid for the quantity and quality of work they do.

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

Perhaps if I fully understood the position I would be in now when I was 15... however that is impossible. I also can’t imagine what else I would have pursued.

Do you think the current state of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

If people are aware of the financial situations of architects then maybe they will pursue something else and architecture will stop looking like such a glamorous field. I think in certain ways it is already affecting the field, there are more architecture graduates than professionals entering the field. I will certainly not be encouraging my kids, or anyone that asks me, to go into architecture.

How old are you?

27

What's your nationality?

American

Where are you from?

Kentucky

Where are you currently enrolled and for what degree?

Princeton University, M. Arch I

What is your prior educational background?

BA Architecture

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation?

Approximately $90,000.

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

No

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

No

Do you expect to be able to pay off your debt in the future? If so, when?

Eventually, I expect it will take a while. Maybe 15-20 years.

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

Yes, but I don’t feel that my expenses are unreasonable. It certainly was a concern in where I chose to go to graduate school. I didn’t want to take on more than $100k in debt.

Will your debt affect decisions like, for example, being in a smaller firm versus a more corporate firm?

I think debt affects many people’s decisions later on. When you’re deciding on a graduate school, people tell you to go the best school possible. Unfortunately, many of the “best schools” don’t offer much financial aid. Fortunately, I got lucky enough to receive a decent amount of funding; but still, I will come out $90k in debt because of the fact that I cannot afford to pay my rent and living expenses while in school without loans. Even for the best students with full scholarships, student loan debt can really add up. And that affects where you work afterwards, because architecture just doesn’t pay much. Personally, I hope I don’t have to make that decision.

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

Yes, I’ve always planned to teach architecture. It’s the only means to a steady paycheck and some freedom to have your own office.

[Teaching] is the only means to a steady paycheck and some freedom to have your own office.

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

I try not to think about it. When I do, I get overwhelmed. My parents still don’t know how much money I have borrowed for my education. While I have a very generous scholarship, the cost of living is killing me. I’ve never talked to my fellow students about debt. It’s somewhat taboo.

Does your debt scare you? Keep you up at night? Do you ignore it? Broadly speaking, can you describe the emotions you experience when thinking about your debt?

I ignore it. Or try to ignore it. I try to assure myself that it’s normal, most people aren’t able to afford to go to school by paying out of pocket. But it’s there, and it won’t go away, even if I were to declare bankruptcy.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

I was unaware that architects make so little. Of course architects are underpaid, and the discipline is swamped with people. Today nobody needs an architect, it’s surprising we still have jobs.

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

Probably not. I guess I just like being poor. Even though I’m poor and probably will be for a while, architecture makes me feel fancy.

Do you think the current reality of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

I think it’s a problem larger than architecture. It’s mostly an American problem. While we enjoy the best schools in the world that have a wealth of resources, we also pay the most for it. Europe pays little to nothing for their education. But most of my European friends aren’t happy with their education. It’s a difficult balance…. We can ask to pay less for our educations, but simple economics will dictate that we will be receiving less. At the same time, isn’t it unreasonable to think that some students graduate with $200,000 or more of debt? It’s a balance we should look for.

How old are you?

25

What's your nationality?

American

Where are you from?

Harrisburg, PA

Where are you currently enrolled and for what degree?

Graduated from Kent State University with Master of Architecture – 2013

Graduated from University of Cincinnati with Bachelor of Science in Arch - 2011

What is your prior educational background?

See above

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation?

$130,000

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

Yes, about half

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

Yes

Do you expect to be able to pay off your debt in the future? If so, when?

Yes, hopefully not more than 15-20 years

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

I’ve accepted that everyone who was not born into money will have student loan debt, regardless of profession, and it is just something you have to pay off while you progress through your career

Will your debt affect decisions like, for example, being in a smaller firm versus a more corporate firm?

No, I think the pay is relatively the same, I currently work for a very small firm

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

Yes, I plan on “moonlighting” once I get my license

I think that in order to get paid well you have to be a standout, you need a higher level of design, higher class of clientele.

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

I think it about it once a month when the bill comes, at this point it is not worth thinking about more than that, I just have to pay it.

Does your debt scare you? Keep you up at night? Do you ignore it? Broadly speaking, can you describe the emotions you experience when thinking about your debt?

Like I mentioned above, I don’t really think about it. It is daunting when you think about “wow I make $45,000 a year and my debt is like 3 times that” but currently there is nothing we can do so it’s not worth worrying about, just keep making payments.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

I think that in order to get paid well you have to be a standout, you need a higher level of design, higher class of clientele. It is hard for many people to do this, which is why so many architects seem “underpaid.”

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

Probably yes, but I have always wanted to be an architect and the way I see it, I’ll be making enough money eventually in my career that my student loans will be paid off and I can live comfortably…because of the fact that I got a loan to get the proper education

Do you think the current reality of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

It may make more people not want to pursue architecture or any degree that takes more than the average number of years to complete. I do not think that people who are passionate about architecture will be swayed by how much it costs to get there, though.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

61 Comments

Thanks for posting this. Truly important and I don't think that Gen-X'ers or Boomers really get it.

I am glad to see Archinect addressing this issue and making an effort to truly understand the situations and sentiments of current students and recent graduates. I found that especially the first interviewee above (from Chicago) brought to light a lot of thoughts and feelings I have been seeing from recent graduates like myself in regards to their debt and the situation they find themselves in. I think that this is an incredibly important issue that will affect the field in the years to come, especially if it is not addressed in some way. As much as many of us have true passions for architecture and design, it is becoming increasingly difficult to stack those passions up against the situation many students must put themselves in to pursue that dream. I think we will hear more and more architecture students admitting that they may have made different career choices had they fully understood the debt situation they are finding themselves in.

There have been many discussions on the issue of fewer candidates pursuing architectural licensure. I think that any discussion of that topic is incomplete without acknowledging the debt situation as a factor. Simply put, it is expensive to get licensed. Application fees and testing fees and study materials all add up to thousands of dollars that recent graduates often cannot afford to spare.

I see this as a somewhat minor consequence of the larger debt issue, which threatens to scare away promising talent should the word get out about the situations recent graduates find themselves in. Don’t we have a responsibility as a profession to current and future architects, designers, interns and students to not accept that the situation (in architect-speak) “just is what it is?”

It's interesting how it effects young people's mindset about money. I for one feel very apprehensive now about using a credit card, because I don't like spending money that isn't in my bank account.

alt - if you're a boomer with college aged kids (or an 'x'er like me with one approaching), you definitely get it.

with that said, and not to diminish the discussion, but isn't this a much, much broader problem with higher education right now? architects aren't the only ones affected (at all) - teachers (secondary, career), many lawyers - it's a financial equation that isn't working for quite a few professions.

promising talent's leaving the field to be sure - not just for reasons of student debt either. at the moment, though, unless you have a magic bullet somewhere that can remedy fees for the profession overall, how do you propose 'we' correct the situation for the future? the 'it is what it is' usually isn't a selfish turning of the backs but rather a recognition (borne from years of experience) that changing this equation overall isn't something that can be done externally or very willingly internally. so... how do we all make more money? because i don't have any to give you...

@Gregory Walker

you're right. it's not unique to architecture. educational institutions can get easy money from the federal government; schools get cash when their students enroll with federal debt. but schools-- who have already gotten paid-- are entirely insulated from any fallout if the student later defaults on those loans.

solutions?

- intervention by the federal government (this is really a consumer protection issue) - schools should be answerable in some way when their students can't service their loans. schools should be on the hook for churning out students who default because they're un/underemployed.

- attrition at architecture schools: sad to say, but schools are market-driven businesses, and decline in enrollment will force universities to bring prices down. but ivies still have cachet and will happily enroll lemmings - highly unlikely their costs will go down soon.

- limit access to student credit for architecture degrees; extend credit (i.e. federal student loans) only to the best and the brightest - the architecture industry is shrinking. don't let the federal government expand the glut of architecture graduates.

- open the conversation: as the above article shows, people don't like to talk about debt because (a) they're ashamed, (b) they're avoidant. expanding the conversation about this issue, and to get this out of the confines of internet fora, is an important first step.

I am at the end of gen x but went to grad school with gen y.....................undergrad was $63 a credit hour freshman year, but at the end of my 5 year. B.arch was $125 a credit hour.....had only 23k in debt, so a 27k starting salary wasn't bad except it was nyc......by the time I went to grad school 4 years later made about $50k but had paid little on debt.....grad students were getting $70k as new employees at same firm so besides being bored out of my mind I thought grad school was a good idea.....one year at ivy grad school was 5 years at undergrad state school financially.......I decided to live the American dream and borrow enough to cover a nice honeymoon and a down payment on a house....left grad school with with new school loans of $100k.......living the American dream in the bur s with wife and kids is not cheap.....I make just over 6 digits these days but have a even larger debt while trying to keep up with middle class America and having licensed...student loans still at $100k+.........to be frank - I don't care. Good beer or put more towards student loans - I take beer any day....remember kids, like the wealthy lawyer up and settle......the system is broke so I do not function properly when it comes to re-payment...

Back when I was deciding between several programs I was interested in for a B.Arch my father strongly advised me to take the cheapest one, no questions asked. So I went where I got a good scholarship at a less prestigious school with ugly facilities. A few years into my career now I think this was great advice - I don't have to worry how I'm going to keep up with payments and have been free to move around following my interests.

I think the worst effects of student debt aren't going to become clear for a few more years - at which point the obstacles of IDP and debt will mean very few young architects in the US actually take the leap and start their own firms. Interesting and new architecture will come from elsewhere where reasonable people can afford measured risks.

Olaf - was the experience of premium-price grad school worthwhile? Do you feel more capable as an architect or find it led to better work?

Greg - I think the biggest thing that needs to be done is to make prospective students aware of the real burden of debt. It's tough for a high-schooler to appreciate how expensive $100,000 debt is, or that a $50,000 doesn't mean you can pay the loans back in 3 or 4 years.

When I was starting out, this didn't seem to be part of the conversation. Except for my father, most people advised me to spend whatever it takes to get a good degree.

Now I see this changing, which is definitely good. The problem is going to be the young students who aren't so aware of what's going on, and perhaps didn't have parents who went to college. They will be very susceptible to the self-promotions of over-priced schools.

At the same time it would be prudent to scale back the student loan guarantees, forcing schools to depend on the actual income available from students. Perhaps a program to reimburse schools for enrolling low-income students who successfully graduate would help improve fairness without encouraging price inflation.

Midlander grad school cured my boredom and got me out of a rut. Not financially worth it............your fathers advice is best and I always recommend do 2 years at a community college then do 2 more years at a good state school then do your graduate studies at your original school of choice....one of my brothers is doing just this but not doing grad, he will be a petroleum engineer, starting salaries about $150k

I agree, midlander, that the reality of loans should be made more apparent to students. not sure how to do this beyond having a face-to-face with each borrower and showing them their likely starting salary, amount of loan payment, amount of rent, car, food, etc. and making it very clear how those numbers stack up.

I showed my ProPractice students once how much fee I was getting on a project and how that compared to my firm soft costs and what annual salary it worked out to annually. They were not pleased by it, as what had seemed like a nice tidy fee amount just vanished immediately when the reality of costs came into play...

My parents encouraged me to go to college and I knew from a very early age that I wanted to be an architect. I never knew that I would be completely on my own financially, however, nor that I would need 8 years of education to attain that goal (1 year at community college, 4 at state school, 3 at grad school), and not to mention AREs for licensure. My debt exceeds $250k. It is an amount I will never ever fully payoff, thank god for loan forgiveness. It wasn't until I saw that first loan bill that I thought "Jesus Christ, is this really worth it?". But while in school, I never once thought about quitting simply because of the financial repercussions. I had my eye on the ball the entire time, and I cannot imagine a different career for my life. Everyone told me "don't worry about it" and just do what I needed to do to graduate and I could pay it off down the road. But they were wrong: my parents were wrong, financial advisers and professors were wrong. I do not blame anyone but the system, and it was ultimately my decision, but you cant help but feel a bit like you were taken advantage of.

It is a good question to ask, how are we dealing with it? My education, hard work and dedication has got me an amazing job working for a world-renowned architecture firm. I go to work every day and solve problems and design for a living, and I am surrounded by interesting and talented people. It can't even begin to compare this life to the alternative... waiting tables? If it cost that much to attain a happiness in my life and career, so be it. Is it right? No. But I'm dealing with it.

I love this quote "Even though I’m poor and probably will be for a while, architecture makes me feel fancy"

@natematt only 1 of 3 (1 of 5 if you count Olaf and starling) gives impression the are overly worried or seriously affected/bothered (health/stress etc) by the load. Or would make different choices/do something they don't love. Though agreeing that it has narrowed their career options/choices.

@Gregory Walker you are correct re: cost/debt as a broader problem with higher education right now. That being said it seems there are more opportunities for teachers to get better/various loan forgiveness options [working for fed/state governments, a 501(c) etc]. An avenue that seems less available to people in architecture fields. Perhaps outside of public interest/social design groups.

Nam, and everyone: if you're interested in loan forgiveness options for architects then support H.R. 4205, the National Design Services Act, which seeks to provide loan relief for architecture school graduates working in non-profit ventures such as community development groups.

At the moment it only applies to graduates of accredited Master degree programs, so maybe also agitate for BArchs and BS Archs to get relief.

Nam,

In replying to natematt's quote, you observe that only a few posters are apprehensive about their financial situation in the here and now. I think you're missing the point.

Having an entire swath of the population living indebted and in prolonged, financially precarious situations will have big impact on the US economy in the long-term. Financial emergencies are an inevitability for most people at some point in life - people mired in debt aren't going to be able to deal with these types of emergencies when they arise.

Economist Tyler Cowen has written some interesting points about how educated people in America will likely find themselves in more financially precarious situations in the future. Check out the article if you get a chance:

Cowen believes the wealthy will become more numerous, and even more powerful. The elderly will hold on to their benefits ... the young, not so much. Millions of people who might have expected a middle class existence may have to aspire to something else.

"Imagine a very large bohemian class of the sort that say, lives in parts of Brooklyn," Cowen explains. "... It will be culturally upper or upper-middle class, but there will be the income of lower-middle class. They may have lives that are quite happy and rewarding, but they may not have a lot of savings. There will be a certain fragility to this existence."

http://www.npr.org/2013/09/12/221425582/tired-of-inequality-one-economist-says-itll-only-get-worse

I guess the question is, Donna, even if we promote loan forgiveness programs, wherein the federal government forgives pre-existing debt, what are we actually changing?

Students will still have to make loan payments for LONG periods of time (with the chance that Treasury Regulations or statutes change in the interim). Nor will every architecture graduate get a job at a nonprofit, so the NDSA is far from a panacea.

Schools will still have access to easy money.

Taxpayers will still cover costs of educations that architecture students can't afford.

Agreed, Alternative. The problem of debt is much bigger than the NDSA. The NDSA is one small part of helping, but it's not going to solve debts for the vast majority of grads.

@Alternative good points to which i agree.

I just find it interesting/puzzling that more folks aren't affected by the level(s) of debt. Perhaps, as they say just can't imagine doing anything different or it is just the normative state and so not questioned/concerning.

It makes me feel like I did the irresponsible thing by going to college. Like, I wasn't "living within my means." But is that really the answer? That you shouldn't take on the debt if you know you can't pay it back? Just go to bar tending school? That can't be what the "responsible" choice would have been. I love my job as an architect and I'm really contributing to the economy and society. However, there is no way I can consider beginning the licensing process since I use my time after work and weekends to take on side jobs to pay for living expenses.

ive heard of people leaving the country to avoid repaying the debt.

there is only one solution. public school being k-12 was established when a HS education actually meant something. now it means a job flipping burgers. we need to re-design the public education system to accommodate 21st century demands. State universities should be part of the public school system up until a BS or BA degree. how do we pay fpr it? stop spending so much money on war.

@jla-x:

we, as a nation, spend much more money on K-12 education compared to countries that destroy us with respect to math and science (among other subjects).

http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/12/american-schools-vs-the-world-expensive-unequal-bad-at-math/281983/

The problem with K-12 education has less to do with spending and much more to do with entrenched teachers' unions that allow for overpaid, shit educators to keep their jobs. if we were able to free up funds paid to terrible teachers to increase pay for talented, better candidates, we'd arguably see a difference in the real of K-12 education.

politically unpopular to say so, but it's true and there is a sea change regarding this issue (http://www.npr.org/blogs/ed/2014/07/28/336050469/teacher-tenure-challenge-spreads-from-california-to-new-york).

Looping this back around to the student debt issue, we don't equip high schoolers with even an ounce of financial literacy. They shouldn't be making life-altering financial decisions relating to student debt.

teachers are overpaid?

Tenured ones who should have been fired long ago are overpaid.

another way to interpret Nam's comment and observation is as follow:. sure there are a lot of people that appear to be "imprisoned" by debt, but if most these people don't really care , what is the cultural value of this economic barrier? As far as I can tell wealthy people are considerably more "imprisoned" than I am, especially heirs to an empire that did not grow (who often are the worst clients because they can never be negative on their inherited capital)

I hate money but I like work, especially architectural work - which often makes me a bad business man as an architect.

so the debt thing in a really ass backwards way really does make American's the hardest working innovators out there, much like our frontier forefathers.

If I had a cancerous tumor but didn't care, would it not be a problem?

@olaf exactly, thanks for explaining better...

The problem with K-12 education has less to do with spending and much more to do with entrenched teachers' unions that allow for overpaid, shit educators to keep their jobs.

NO - this is the problem with education - that people for some reason seem to think that if we only get rid of the "bad teachers" that we'll be ok. The ACTUAL PROBLEM is shitty school boards and administrators. we have morons running our school districts - that's what makes them shitty.

you know there's a problem with top management when they start going after the people at the very bottom. it's as if microsoft said "if we only got rid of our coders, then we'll have a better operating system." or a firm that is struggling decides to fire all its production staff... it's idiotic. and people for some reason seem to think it's different with education.

if you want to change the culture, you need to start at the top.

Alternate - a cancerous tumor is more like being hit with a baseball bat than a letter in the mail stating you are behind on your bills.

you can't negotiate with a cancerous tumor or ignore it or have a lawyer make it go away, etc...

analogy no compute.

on teachers' salary

Though there is a lot more to teacher quality than just salary - few good teachers enjoy working with bad students or lousy parents for one thing. And which is better: 1x Great Teacher@$120,000 teaching 30 students, or 3x Mediocre Teachers@40,000 teaching 10 students each?

There's more to a good education than good teachers. People over-study the aspect of teachers' salaries just because its easy to quantify.

Some interesting data to browse:

Avg Teacher salary by state

Spending per pupil by state (scroll down) note that administration is roughly 12% overall costs

High School Graduation rate by state

If there's a correlation here I don't see it. This article gives a nice overview of the problem in separating performance from background conditions (are students good because the schools are good, or because they have good parents and comfortable lives). Student performance correlates strongly with affluence, and not so much with spending. Some of the best and worst districts both spend a lot of money, but none of the best districts are poor.

Of course, none of this really relates to the problem of university debt! The people going into megadebt for that GSD diploma (or even just 4+2 years at Midwestern State University) all had excellent K12 education and probably could do the math on repayment if they cared to.

toasteroven, I have so much respect for how you are able to stay calm and logical in the face of stupid arguments.

Please, let's keep this discussion focused on college debt, and not get derailed into what's wrong with the U.S. K-12 public school system. Stay focused on college, please.

Germany now has free higher education for all, yes? And many students come from around the world to get s degree from a U.S. institution. What is their debt load like, by comparison?

Donna, 15 years ago I dropped Kansas for one full semester to be a full time German Uni student after doing a full year of exchange program at Dortmund. My parents at the time had moved back to Germany. I was 20 and was in the German system so they received about $150 in child support which paid for my dorm/student apt rent. Unlike the US your hand is not held every step of the way, a hand isnt even offeredd - you're an adult you figure it out. Lectures were optional, you only needed to pass the exam or deliver at jury. I spent most my time in bars, clubs and traveling and kept 2 and 3 grades which all translated up to A and B in the states. I did spend a good month locked up in my dorm room reading 1000 of pages prior to exam with the occasional Irish lad convincing me to do disappear for a weekend drinking.......you can not expect Americans to be this accountable for themselves when it comes to staying focused and working hard at working hard. Our culture can not support such institutions. Not just socially but on an individual level as well. In the US its never your fault.

Donna to add to my post, on the way to office you just reminded me of a whole bunch of other points I'll put into rambling format story...

Tuition was FREE for me, most my flat mates (English English translation) were older than the average US student, but you graduated with a Masters by default. One of my room mates thesis project for Computer Science (Infomatiker) was how to scan with photos and GPS equipment city facades and convert into 3d virtual reality (15 years ago) for gaming. The other taught me 3dsMax Version 2, also a computer science guy....

The expenses I had were Beer and Chocolate and lots of Turkish Doner Kebab's. I had won a Treks mountain bike back in Kansas and shipped it over so transportation covered to.

I later sold that bike to a buddy from West Africa who tried to hook me up with translation work so I could have an income while staying in Germany, architecture work was very hard to find - well paid work, enough to support yourself. The A/E papers I did alright on, but bombed the rest and got fired - like foot, my ass, wtf... I'm bad at both English and German and don't actually translate the words like you should if the other language was a real second language.....some things you can say in German, somethings you can say and English and you can not translate them without loosing meaning....

Anyway, same buddy for his thesis on insulation material in tropical climates actually was commissioned while in school to develop the research for a German company, enough to buy a nice car.

So in short, not only was Tuition free, if you were doing something valuable within your field you could make money as well. Complete inverse here, granted my buddy who established himself quite well without knowing anyone in Germany coming from West Africa was quite the business man, usually you have to drop out first in the states to make good money on your idea that a professor might take and put on their recent convention abstract...

like Olaf says - the debt thing keeps American's working.

Donna, K-12 is relevant to the problem. What I was saying is that it should be K-16. the 4 year degree should be free and integrated into public education.

Yes, I agree jla-x. I just don't want us going down the rathole of "fixing" public K-12 as it will derail us from talking about architecture school, and architecture debt.

If we want to talk about making college education free, or even vastly less expensive, I agree, I think we as a country and society should be doing that. Which is why I brought up Germany, as they have done it.

In my opinion, and this affects architects both practicing and in school, college tuition has gone up astronomically in part because colleges are spending so much on ridiculously overpriced frills like rec centers with lazy rivers. So while practicing architects are making money on capital improvements, students are having to go deeper into debt for more exercise bikes.

now it's time for free education! now that the lazy rivers have been built we can be assured our future leaders will be ready for life.

just remembered this link -

http://nautil.us/issue/17/big-bangs/how-i-rewired-my-brain-to-become-fluent-in-math

it's half the full essay - but addresses jla-x and Donna and Ken via Archinect Podcast - the importance of demeaning education - ROTE (door hardware schedule)

with that said, as an illustrative suggestion on why FREE secondary education will never work with the US culture I provide my visit to a Dortmund Municipal building in the year of our lord 2000 AD to renew some permit of some sort. I'm a US citizen by the way, even though I was born in Braunschweig, DE - it doesn't work that way there or most other countries...

I'd heard from this ex-physics German turned architect, studied at Kansas on an exchange program, leather pants wearing -gay lisp in English, macho male Auf Deutsch...can't make sense of that...He said - if I really wanted to experience an elevator to go to this Dortmund Municipal building.

The elevator was a vertical conveyor, like one of those water wheels or even a merry-go-around without doors and never stopped. The doors were always open. Left entrance was always moving up and right was always moving down.

At 20 years old and agile I was slightly concerned about my timing. It's an escalator but moving up and down and if you don't time it right you can get stuck at the head or sill of the door.

Most people took the stairs, but I said - fuck it - you live once, I'm 20, I can time this German machine, took the the moving carousel upstairs.

Got in line, waited hours to meet a nice young lady who had a giant poster of Chicago hanging up on her wall.

Auf Deutsch "Chicago? Nice place, when did you go there?" - me

"Never been there. I've been saving all my live to visit the US and all my friends are telling me Chicago is America!" - clerk

"Well, I'm midwest American sort of, although born in Germany...you are right, Chicago would make the most sense for Ruhrgebiet, hard working... It's windy!" -me, still Auf Deutsch.

She'd never been there (US), wants to be there Chicago.... I'm here (there in Dortmund) and we Americans sure as hell can't have an elevator like that, without some moron mistiming their step and suing and ruining it for all of us.

Do you know why it is so hard to get anything done in NYC? Because some guy did it wrong, and the rest of us that are doing it right can't seem to check all the boxes on the paperwork correctly....wait this goes for all things in this country, one moron, one asshole - makes it that much harder to be a decent Citizen.

In very short, we don't deserve FREE secondary education here in the US, we can't handle that responsibility. This means we would have to deliver productive services beyond that which can be measured in the forms of capital - late late capitalism... mind you the Germans produce 11% of the I-phone vs 23% South Korea, 32% raw material worldwide, 6% assembly in China, and guess what only 6% PERCENT US - that I-phone.

Pearl Jam is blaring - ONCE

toodles.

Teeter's recommendations for beer while enjoying this read is by the first US trappist Monks - http://spencerbrewery.com/ in Spencer, MA)

^ah, the most catholic of elevators - the paternoster. They're not only in Germany, pretty sure the UK has some too. And this video was I think Prague.

So, the essence of your argument is that free university education is great, and Americans don't deserve it? I mean, neat old elevators are neat, but it's to America's credit we've replaced them all with elevators that children, the handicapped and parents with strollers can use.

I don't see any reason university education needs to be free to all, but it would be good if it was as affordable as say a car. Something a normal person could afford with a few years' savings at median income. It doesn't make sense to put all the cost of developing a new generation of citizens on those individuals - the entire country benefits.

Thanks midlander, was going to try and find images this morning.

my i-phone stat was by memory from Inequality for All (Robert Reich), not totally accurate except for the 6% US. I forgot Japan (34%) and South Korea (13%) was lower, so was China (3.6%) and Germany was higher (17%)...27% other... gettin' old...

Yes Midlander, not only do we not deserve it, but we probably couldn't handle it. In some book by the economist Edward C. Prescott where he essentially states the reason South Korea went from what amounts to third world to leading 1st world industrial country was good economic policy, mainly deregulated....citing the US 50 states and Swiss Cantons on trade for competitive purposes, etc...

deregulation rarely leads to anything good here. free education is the equivalent of deregulated economy.

(no I don't sleep, ha...Honest Tea has replaced Red Bull and Mountain Dew, and I not only feel great, I need less sleep. Go Organic Fair Trade)

I see I didn't make my point yet correctly...

If memory serves me well, Prescott noted that what South Korea did economically with regard to growth in such a short time has never been done and may never be repeated by any nation state on this planet. His argument was good economic policy can do this, mainly policy that deregulates and adapts to interstate trade, etc...

For such a policy to work, and as Olaf notes via reinterpretation of Nam - economic barriers may be meaningless if they do not have real cultural values, inversely economic polices that may allow one culture to flourish may be damaging to another.

The US is not culturally equivalent to Japan, South Korea, and Germany, (64% of i-phone production) so what may work in many countries may not work here.

If the US offered Free Secondary education there is no guarantee the GDP or living standards would improve...you have a better chance of creating more float trips down the lazy rivers and better Home Depot sponsored ESPN Football saturdays, which I love of course...

If you teach, compare your students who pay for school to those who do not with regard to focus and self-improvement.

If debt is not a cultural incentive for economic improvement anymore, I believe we have a serious problem now.

See Nam Henderson's earlier post.

What if we tied the cost of education to the expected salary to be earned by a graduate over their career?

I was thinking that in the terms of military service Beta...but don't think I got there in my rambles.

If you take education as an part of the Economic engine then I think you have to re-think the tuition fees, especially based on major, etc...

Good point Beta!

Nope, you can't tie loans to expected income. Some people will go to Wharton and fail at everything they attempt; some will go to art school and become millionaires, even doing something not directly related to their field of study (David Byrne is the first example that comes to mind).

Chris I hardly understand anything you've posted here, but I did get this point: in comparing students who have to pay to go to school, or who have very-much-needed academic scholarships and therefore have to keep their grades up, as compared to those who come from wealth, my VERY BROADLY GENERALIZED experience is that the ones who have to struggle harder to be at school work much harder to try to make the most of their opportunity.

I also agree with midlander's point: maybe university doesn't have to be free, but it should very much be affordable. an investment, to be sure, but not one that costs as much as a house.

There are a few things going on here.

The first is that the educational system's capture of the policy-making bureaucracy has allowed institutions of higher ed to position themselves as monopoly gatekeepers on employment credentials. This has insulated them from market forces that might otherwise force them to price competitively. It has also allowed them to extract enormous rents and privileges from the government (e.g. student loans are legally non-dischargable, most universities are 100% financially dependent on huge grants from the government, etc.).

The second is that the ongoing credit bubble and rampant labor arbitrage which has plagued the USA since the late 1960s has been eroding the wealth and position of the middle class dramatically, to the point where much of the middle class can no longer afford the higher education credentials on which their social position is dependent. As a general rule, if you have to borrow money to go to university, you can't afford it. Even setting that aside, from a financial standpoint, nobody should borrow more to pay for an educational credential than one-half the expected value of the first-year's salary (salary[EV] being the probability of gaining employment at that salary level times the salary amount, and then assuming a ten-year pay-down at 5% of gross salary per year maximum). Since starting salary for newly-graduated architects is averaging around $35K to $40K right now. Which means a maximum cap of $20,000 for total student loan debt for the entirety of the degree credential. If you need to borrow more than that, you REALLY can't afford it. Do something else. Besides, not everybody should pursue higher education. Really, only about 10% of the population should be doing so, which was the standard prior to the GI Bill and higher ed bubble kicking off.

The fact that student loan debt is non-dischargeable in bankruptcy means that we have effectively re-instituted legal debt bondage. The fact that payments on student debt are now the US government single biggest source of revenue also mean that the government has an incentive to only increase the debt amounts and repayment strictures to further obligated borrowers and gain a permanent claim on their labor.

The third is that at the higher end of the social scale our society is producing a massive over-supply of aspirational elites, and the university credential system is a primary means by which that is happening. [http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2013-11-20/blame-rich-overeducated-elites-as-our-society-frays] In short, way too many people are going to university, and doing so with an expectation that university credentials will give them an entrance pass to the elite classes. This huge surplus of credentialed aspirational elites is causing all kinds of social and political problems.

This all plays out in the architectural profession as follows:

1) University architecture programs have gained a monopoly (and thus associated rents) on professional educational credentials for architecture (via NAAB, NCARB, etc.)

2) University architecture programs are granting vastly more architectural degrees than is necessary to meet market demand (labor over-supply).

3) Architectural education is time consuming, and thus expensive for students. Five-year BArch programs are being discontinued nearly everywhere because universities realized that the pro-MArch1 degree (which is exactly the same thing) can get them one additional year of tuition income. This leaves many architectural students who do not come from upper-middle-class or higher backgrounds saddled with substantial debt necessary to pay for six years of farting around in studio. And that doesn't even count the opportunity cost of devoting all that time to earning a credential which commands a low starting salary and a minimum of three years indentured servitude to qualify for licensure.

4) The overproduction of architectural graduates (most of whom are burdened with debt) has many of the same kinds of knock-on effects that Turchin describes for lawyers and MBAs in the article I linked above. Thus competitiveness among architects has become extreme and problematic, at all levels from unemployed interns to senior partners. This has brought with it a host of negative effects for the practice of architecture per se. We are in the habit of ascribing many of the negative effects to client short-sightedness and host of other things, but actually we are doing it to ourselves because there are just too damn many of us, and too few outlets for our various ambitions.

Donna I will go ahead apologize here for my rambles. I work a lot out here on Archinect as far as thinking goes, like a designers do, take the context, the comments, and ramble through it...........gwharton - fantastic post. Gwharton, would it be safe to say our culture has trumped economics as far as education and training go, and any attempt at more economical models may be construed as limiting civil liberties?

thanks GWharton. I think you've given a thorough overview of the conditions leading to the overpricing of academic study in America.

RE the 5 year b.arch: I've actually wondered why this degree takes 5 years as it is. I suspect it's a sense of puffery, the NAAB or universities stretching to make the professional degree more difficult than a regular 4 year bachelors.

I probably sound like a bitter crank going on about this (maybe I am?) but it really doesn't need to be made so difficult for prospective architects. There is a lot of material in B.Arch programs that doesn't serve the needs of future professionals and no longer relates to the practice.

As an example: I recall we spent about 5 semesters in the calculus-physics-structures sequence which is entirely disproportionate to the amount of time architects spend on this in practice. The hard things in structures - dynamic loading, winds, seismic - are beyond the capability of architects to analyze; we can only rely on rule-of-thumb guides and seek engineering input. The same could be said of MEP systems. Most of the value experienced architects provide in this is simply knowing common practice, usually informed by the experience of working with capable consultants - not a skill school helps us develop.

My point being all of the structural courses could probably be condensed into one or two semesters for by-the-book calculations for simple conditions, and a general introduction to the principles of seismic / wind / dynamic load calculation which are beyond our capabilities.

Likewise the first year of studio which was "fundamentals" of mostly tangential relevance. Lots of hand-drafting bottles and chairs, some axons of simple buildings. No design at all! Maybe we could skip that and have students learn to draft by drafting what they design. And do it in CAD. Because while we can discuss the value of sketching in the design process, there really is nothing to talk about regarding drafting: in practice drafting is done as CAD/BIM.

TLDR: My point is that if you can find the work architecture isn't that hard. Great design is, but that's not exactly the remit of the professional degree. Competent young architects could be trained adequately in 4 years if we cut out some of the fluff in b.arch programs and recognized the real role of architects in current practice. The M.Arch II would remain for those who desired a more nuanced appreciation of design.

@ midlander, supporting your last point

1 - Architectural Engineering Degrees do not appear prevalent out East as they are in Midwest. At KU these engineers did 4 semesters of design studios.

2- After studying at a quite technical school in Germany and practicing I would have complained less about my education had I studied for an Arch. Eng. (PE eventually) and not B.Arch (RA). Either way, as applicant of record in NYC and most places PE/RA is pretty much interchangeable. I spend most my time working for an A/E firm and doing very much A/E stuff consulting (technical).

3 - Design is very much based on personality and the social conditions of the design office. Design for the most part is an intangible and no number of studios will make you a better designer.

4 - I taught in a program where skills were directly taught to students. At 2nd semester presentations, jurors who taught in other NYC B.Arch programs were blown away by what would equal 4th and 5th year B.Arch presentations. (not design, presentation).

5 - Same program graduated students in 3 semesters, who often had prior degrees or work experience, but either way, having hired a few, noted where they were hired (very successful Architectural Design firms) - 3 semesters with integrated skills is more than enough to prepare you for Architectural design.

6 - You have to work 1-3 years anwyay, depending on state, prior to sitting for exams; so anything missed in school will be picked up in practice. Or as many practitioners note "I have to teach the entry level kids everything!"

Midlander, a 4 year double major with sitting for licensure after 3 years is affordable I think.

You could easily teach everything necessary for foundational skills, knowledge, and methods for architecture in less than three years of formal training and education. It's not like it's that difficult. But university business models are now dependent on getting four or more years of tuition out of every matriculating student. More so for specialized programs like architecture.

None of that is going to change until the power of the education-bureaucratic complex is broken. And that's not going to happen until the financial-governmental system that supports it fails. So, for now, it is what it is. The best thing to do, if you want to be an architect, is engage with the educational system as little as possible. Get an accredited degree as quickly and cheaply as you can manage (BArch or something at a state school where you have residency, or go the ArchEng/PE route Chris Teeter describes). DON'T go to graduate school (it's a complete waste unless you intend to become part of the educational pyramid scheme yourself). And for heaven's sake, don't borrow money to do any of it. Some states still haven't closed the alternate path to licensure loopholes, and it's still possible to use work experience in lieu of a degree. If you can't afford a degree, move to one of them and do that.

As for the broader problems, there are some basic things we could do to address them and turn the situation around quickly. But they are all politically impossible until something more fundamental changes in the power structure and priorities of our society. In the meantime, the middle class is going to continue getting screwed harder and harder by the high-low coalition which rules us and hates us.

the costs of university education has increased approximately 1200 percent in the last thirty years. More money goes into the pockets of the administrations of these universities and in addition to the increases in tuition, the amount of time it takes to earn these professional degrees has also increased. i feel that all students graduating with a master of architecture should be registered upon completion of their degrees. that should be the requirement. now i know some will argue that if you have no real world experience you can't be an architect. well, have you looked at the a.r.e. lately. seven exams could be covered in seven semesters. there is zero design on the a.r.e. so, while one takes a semester course in construction documents it can be augmented with a design studio.

the challenge now for those studying for the a.r.e. is that there is a real lack of camaraderie. one can take the test anytime and anywhere. if you are working in bumfuck louisiana you may be the only architectural intern for two hundred miles. you may have to drive two hours to sit for the exam. when one is in school it is easier to focus on and take an exam. pass the exams graduate a licensed architect. remove all this intern bullshit and get on with being a professional fucking architect. if you need to work for someone to gain real world experience, do it. if you have experience or contacts, hang a fucking shingle and go to work. the university experience should be focused on this. we can still be creative in school. we can still be artistic in school. but we can also do those things, be those things and be registered when we are done with it. until this changes no one should go within a mile of an architecture degree.

i like it vado

I also think that once a couple people get screwed over after hiring a licensed architect w/ no real experience there will be more appreciation for what an architect does

vado, well said!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.