The Illinois Institute of Technology recently hosted the first ever Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize. Unique among the current proliferation of architecture prizes, the $50,000 MCHAP was initiated by dean and prominent Architect Wiel Arets to celebrate the best of architecture in both North and South America.

While punctuated by the usual reception and dinner, the award was much more, with an entire day of activities dedicated to a range of engagement types. In this extensive interface among students, professionals, and the community at large, the award sought to honor, in the words of Dean Arets, "those who acknowledge the interdisciplinary nature of our new ventures. ... who have invested their work with the mystery and power of human imagination... to reward the daring contemplation of the intersection of the new metropolis and human ecology.”

In the ceremony's morning session, students from IIT had an opportunity to sit in small groups with teams of each of the seven finalists, discussing the projects and the practice of architecture in detail. Alvaro Siza, the Portuguese master, was utterly without pretense or ego as he presented the model for his Ibere Camargo Foundation in Porto Alegre Brazil to a small group of students, much as another student might do themselves.

The presentation and discourse surrounding 1111 Lincoln Road, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron’s project, was exceptional as well, with students getting an in-depth look at how practical and planning constraints affect the production of exceptional architecture. In both this morning session and her well-executed evening presentation, Christine Binswanger illustrated that concepts as opaque as floor-area ratios and parking and occupancy guidelines are more than just bureaucratic hoops to be jumped through, and demonstrated how seemingly byzantine constraints such as these can enliven and shape an architectural project and program by eliciting creative responses.

The afternoon session was devoted to a round table discussion between the jury and the finalists, resulting in a unique opportunity for the public in Chicago, one of America's most design-minded cities, to witness up-close the type of impassioned discourse that all architects strive to generate. Joshua Prince-Ramus, on hand to represent OMA for their Seattle Central Library, did not disappoint in this regard, turning in fiery and sometimes bombastic rhetoric about the power (and limits) of architecture to affect social change and generate new modes of living, working, and engaging with society, a theme that resurfaced in presentations by other practitioners during the evening program.

Alvaro Siza walked us through his winning project, the Ibere Camargo Foundation, with the straightforward ease and disarming grace of a great composer of the built form.The evening presentations were given to a crowd which included many of the midwest region’s most prominent architectural practitioners, as well as dignitaries from Portugal, Brazil, Switzerland and the Netherlands. As the first of the biennial MCHAP awards, the jury considered all projects in the Americas realized since the turn of the millennium. Presentation of the projects started with Joshua Prince Ramus taking us on a tour de force of the conception and execution of the now familiar Seattle Central Library. Alvaro Siza walked us through his winning project, the Ibere Camargo Foundation, with the straightforward ease and disarming grace of a great composer of the built form. His manner of speech and straightforward language were reminiscent of Mies van der Rohe’s own writings, and one could not help but feel that we were witnessing, at least in part, a celebration of one of the last remaining modernist masters in the profession.

Rafael Iglesia, architect of the Altamira Residential Building in Rosario, Argentina, appeared via video with a priceless speech touching on aspects of modernism, globalization, structure, and practice, with an ease of intellect and sharp mind unaffected by his advanced age and seemingly precarious physical state. Christian Unduragga appeared briefly only to introduce another video piece, this time an interview with the caretaker of the sublime Capilla del Retiro chapel Unduragga had constructed in Valley of the Andes, Chile. The interview touched on issues of faith, spatial experience, and the suspension of reason in pursuit of higher planes of consciousness - issues rarely addressed in the professional sphere of architectural design or discourse, and which taken together with the stated goals of the prize, provided an interesting juxtaposition to the more rationally grounded presentations of the evening.

Christine Binswanger of Herzog & De Meuron gave the aforementioned talk about resolving planning and design constraints with innovative design. Chris McVoy, Steven Holl's partner in production of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, took the stage and made as much a show of his hair as the presentation itself, constantly rearranging and reconfiguring his coif as he and Holl might arrange light and shadow in an architectural composition.

Cecilia Puga of Smiljan Radic Studio presented the firm’s Mestizo Restaurant in Santiago, Chile, which shares the same tectonically expressive language and large granite support members as his recent Serpentine Pavillion. Following the presentations, one could not help but wonder how the jurists would decide the award, but the presence (and lack thereof) of the principals responsible for many of the projects gave some hints.

The evening continued with dinner and further drinking, a format familiar to anyone who has attended one of these types of events, but a subtle shift in attitudes was evident. Excitement replaced the typical resignation and intoxication. Conversation, unsurprisingly, flowed freely, however much of the overheard discourse went far beyond the networking and self-promotion typically in surplus at these events, to touch on topics that are truly important, and indeed, essential, to the practice of architecture today. Ideas about social organization, hierarchical modes of living, and breaking pre-determined modes of practice are commonplace in Academia, but here were hundreds of practicing local and national architects along with representatives of the world’s best firms, and the conversation was naturally and freely turning towards these typically esoteric ideas.

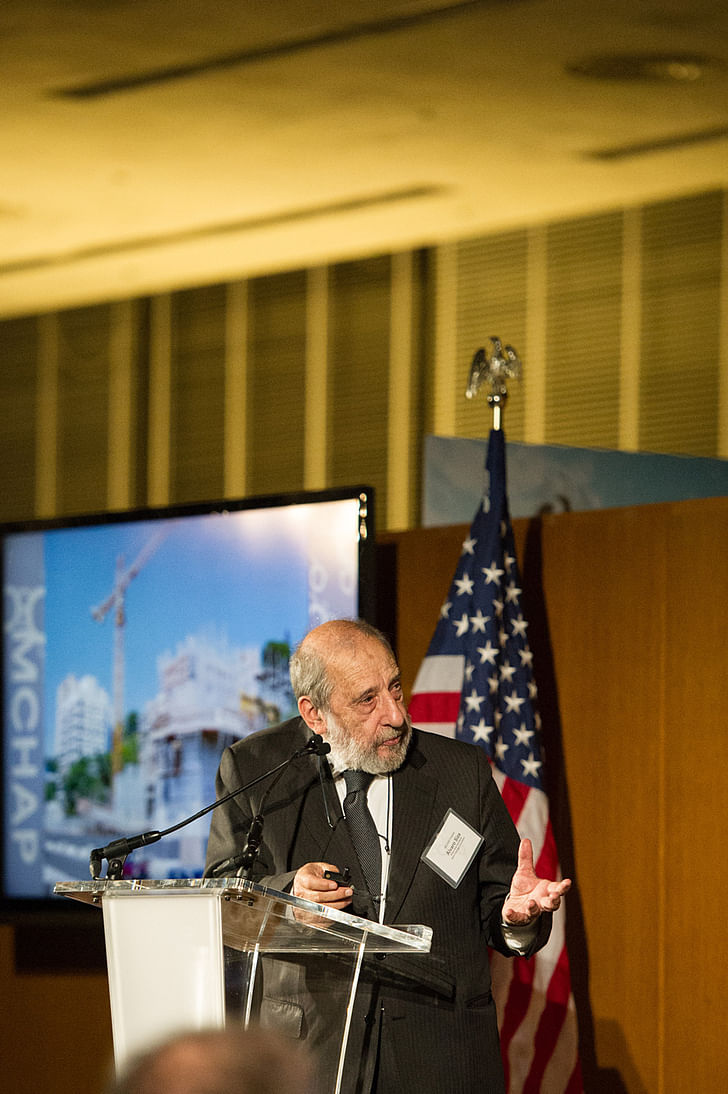

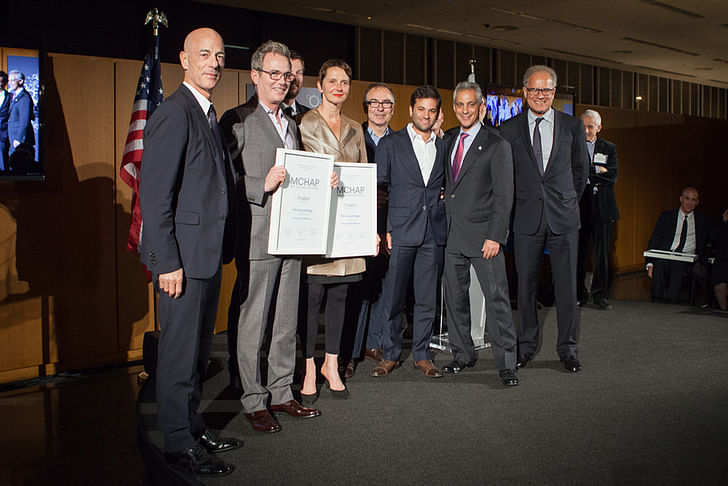

It would have been impossible not to honor Siza, now an elder statesman of Modernist practice, with an award.Dinner ended and the master of ceremonies and director of the prize, Dirk Denison introduced Kenneth Frampton, who would be speaking on behalf of the jury. In his remarks, resembling a densely worded chapter of his theoretical writings as much a jurist’s comments, Frampton pontificated on the reasons for the jury’s unusual decision to select two winning projects, Alvaro Siza’s Ibere Camargo Foundation and Herzog & de Meuron’s 1111 Lincoln Road. As much as we all admire these projects, and likely agree with Frampton’s sometimes impenetrable reasoning, it would have been impossible not to honor Siza, now an elder statesman of Modernist practice, with an award.

Many contested that so many other deserving projects would be passed over in favor of a parking structure.The reactions to 1111 Lincoln Road were more varied - no one disputes Herzog & de Meuron’s greatness or mastery of light, materials, and spatial organization, but many contested that so many other deserving projects would be passed over in favor of a parking structure. Upon further reflection and conversation following the announcement, however, it became clear that no project better exemplified what the award was about. The subtle ways in which the project undermines and subverts planning and zoning requirements as much as its nominal typology are exactly what this prize set out to promote in the practice of architecture.

We can only hope that two years from now, when the jury convenes to award the second MCHAP prize, the unique thinking which allowed this project to transcend its typology and planning constraints will have infiltrated the global architectural community more thoroughly.

Nicholas Cecchi is an architect born in Denver and educated in New Orleans. Following completion of his degree, he worked briefly in single-family residential architecture before leading the design department of a Denver-based boutique architectural and sculptural design and fabrication studio for ...

1 Comment

Isn't Joshua Prince-Ramus now REX? Understanding that he was a key member of design team/Partner in Charge, but OMA doesn't self-represent Seattle Central Library?

Or perhaps, celebration of "best architecture" requires a focus on designer/person behind project, not the broader firm?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.