Working out of the Box is a series of features presenting architects who have applied their architecture backgrounds to alternative career paths.

In this installment, we're talking with Malaysia-born Melbourne-based sculptor and creator of fascinating miniature objects Daniel Dorall.

Are you an architect working out of the box? Do you know of someone that has changed careers and has an interesting story to share? If you would like to suggest an (ex-)architect, please send us a message.

Where did you study architecture?

I did my first degree, a Bachelor of Architectural Science (Hons.) at the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur - completing it in 2002, and then finished up with my Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Melbourne in 2005. I took a year out in between degrees to work in a local practice and prepare myself to relocate to Australia.

At what point in your life did you decide to pursue architecture?

As a child, I always liked building things and fixing electronics. I was a LEGO kid – which I hear is the story for most architects. But architecture never crossed my mind; I thought designing buildings was the job of a civil engineer, so I grew up aiming to get into that profession. The turning point came as I was competing 6th form, and started talking to more career counselors and realized that engineering has nothing much to do with the design of buildings! So I changed trajectory and applied for a spot in architecture school.

When did you decide to stop pursuing architecture? Why?

When I came to Melbourne, the degree structure was more flexible and allowed me to explore other subjects and study areas. I took electives in art conservation, ancient history and classic languages. I began to realize that my passion – while still in the design and creation of buildings – was now leaning more towards the appreciation of beauty and aesthetics. Melbourne is also a city with a large and intense art scene, which I started exploring and getting into.At the same time, the higher level architecture subjects put importance in professional practice and pleasing clients and costs and building bylaws – which all seem to limit the creativity and base level design concepts I enjoyed in my first years of the program.

Melbourne is also a city with a large and intense art scene, which I started exploring and getting into. In my final year of my degree (2005) I applied to have a small exhibition at a student gallery in the University and was accepted. The show was well received and I decided I wanted to become a sculptor.

Describe your current profession.

I have been exhibiting as an artist for almost 10 years now. I’ve had a numerous solo exhibitions and been curated into group exhibitions throughout Australia, New Zealand and Malaysia and most recently in Norway. I have also been fortunate to have received early career and new works grants which have allowed me to travel.

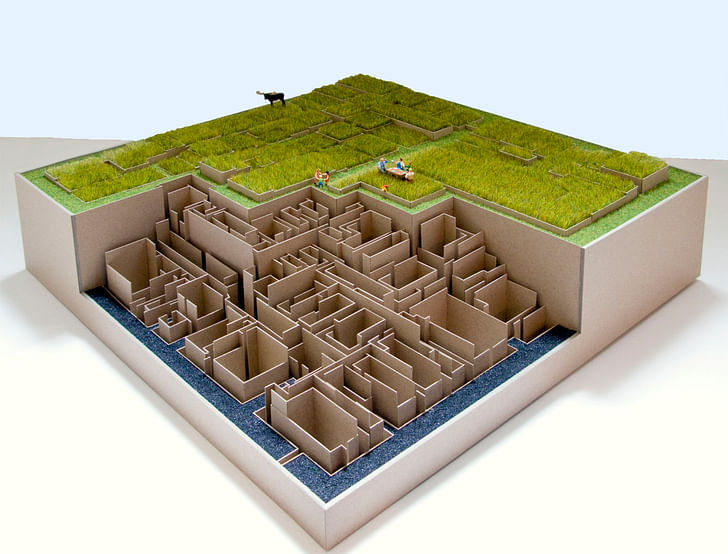

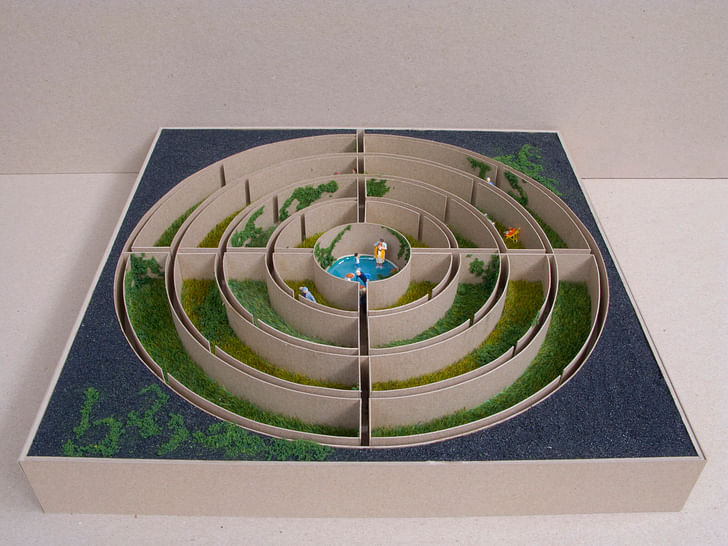

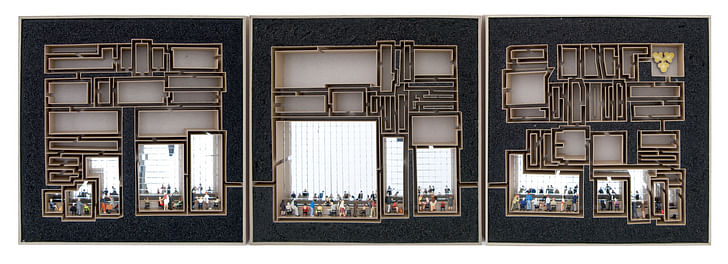

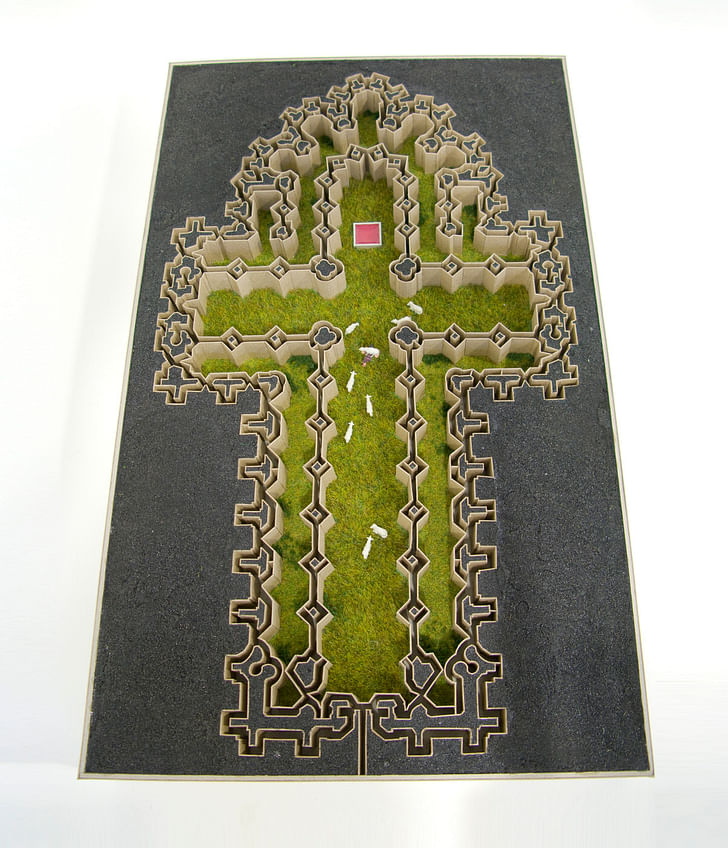

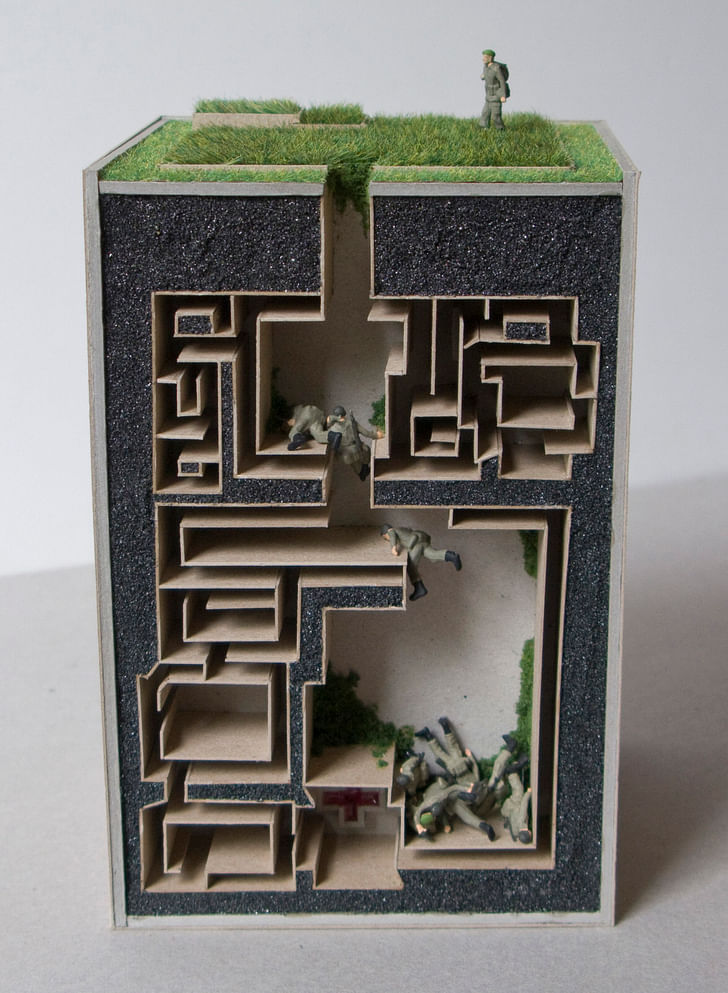

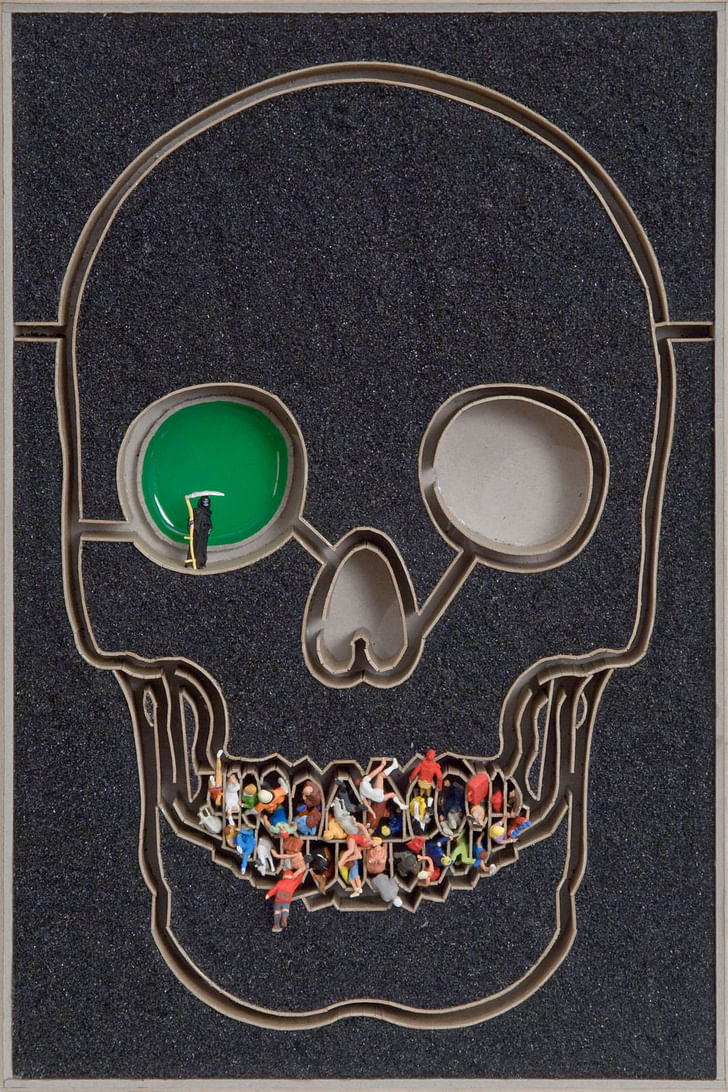

I am very interested in the handmade, the detail, and the ideas linking sacrifice and labor to beauty.In a nutshell, I make miniature objects out of cardboard – it usually takes the form of the maze. These maze-objects would usually contain figurines, acting out scenarios based on urban or cultural (or political) narratives. The objects allow me to make references to popular culture and portray my take on things happening around me, quite often in a symbolic way. Sometimes the figures (or landscape) are there just as composition within the object. I am very interested in the handmade, the detail, and the ideas linking sacrifice and labor to beauty.

Miniature objects and dioramas can be seen as the final sculptural piece but also to invert the idea of miniature=study object and anthropomorphic=final object.More recently I have been creating walk through maze-installations. These room size creations came about when during a floor talk for one of my solo exhibitions, I was asked “So is your plan eventually to create these models in human scale?” - To which I replied that the sculptural pieces were not ‘models’ per se but completed and finished objects. The viewing of my work as models or maquettes for larger works, most likely comes from the medium used – ephemeral cardboard – a material often used for architectural models.

So I set out to prove my point, that miniature objects and dioramas can be seen as the final sculptural piece but also to invert the idea of miniature=study object and anthropomorphic=final object. I began building walk through mazes and have made 6 full room installations over the last 6 years.

What skills did you gain from architecture school, or working in the architecture industry, that have contributed to your success in your current career?

My architecture study has greatly informed my work, most obviously because the scale and medium used is so closely linked to architectural models. It has taught me techniques, how to plan and visualize 3D objects, the importance of composition and the basic values of form & hierarchy. I think an architectural education also made me think more laterally, and taught me how to view things in various angles, which has been beneficial to my work.

Do you have an interest in returning to architecture?

While I don’t currently work in architectural practice, I do work in academic programs for the Melbourne School of Design, which is the graduate school of architecture at the University of Melbourne – where I am involved in the structuring of the subjects and courses run by the Faculty. I also run a couple of projects here and have been involved in business and process improvement, which I seem to have developed an interest for in the last few years. I call it my ‘day job,’ but it really does excite me and also informs the type of sculpture and narratives I imbue in my work.

I also completed a research masters recently in Fine Arts, which was heavily informed by architecture. It dealt with the notion of looking at full size constructions as studies to miniature objects – which is in a way the opposite of architecture, where the model or study comes first. In the paper, the idea of placing a maze installation – which the visitor could meander through and experience – first, before arriving at the maze object, meant that when viewing the object, they could better understand the narrative (after having had this first hand, whole body experience by walking through the maze). Thus the human scale maze acts as the precursor to the object and is thus used as the study, inverting what we have in architecture. The miniature becomes the final outcome, the full size construction – something to aid the viewer to understand it.

1 Comment

Fantastic! Witty and meticulous, really made my morning to look through this. Yutaka Sone is another artist who's done compelling miniatures of architectural (urban) space - but you have a much different take and sense of storytelling.

I would love to see an exhibit in person! Good luck.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.