Written by Nick Axel

The recent project of Open house by Droog with Diller Scofidio + Renfro is refreshing in the sense that it engages a pervasive condition and experience of the built environment that often goes unthought. The idea of envisioning a ‘future suburbia’ has strongly provoked the attention of architects and the non-architect, better known as the resident. The content of the project has to this date contained a one day event that included a seminar taking place in New York City, polemical installations within the archetypal suburb of Levittown, New York, visionary representations of a potential life in suburbia (1), and a host of online journalism. Open house uses traditional architectural conventions as provocative mediums in order to communicate, what I would like to show, a much deeper and significant concept that is at the root of the project. By employing the potentiality of a service economy, Open house fundamentally works on an ideological level that seeks to change the way we view our contextual relations to the people and goods that inhabit the suburban environment.

While Open house has recently been criticized for not addressing the real issues that face the suburb today (2), I would like to view the project differently. Renny Ramakers responded to this initial critique by asking: “Is design solely a form of crisis management and problem solving? Or can design also offer a different perspective on a problem, without having the aim of solving the problem entirely?” (3). In an allegorical sense, if one is sick, is it the symptoms we should try to mitigate, or the sickness we should try to rid? When facing a problem like either the human body or the built environment head- on, solutions are often quite unknown (take the history of medicine for example). In the contemporary situation of the suburb, design has the critical capacity to work in that exact area of the unknown, possibly addressing the problems themselves. Therefore, instead of dismissing Open house as a rather insensitive art project, I plan to position the project within the suburban terrain in order to map a potential territory for the future of a publicly minded architecture in the United States. As this project is addressing quite literally ‘the masses’, I will do this analysis by viewing the material presented as communicative tools attempting to not only communicate these ideas to the architectural community, but to inspire and convince the people actually living inside the suburbs.

Its scope and intentions have been made clear: “Entering the suburbs, we did not intend to resolve the issues it faces, but rather to explore what value personal service exchanges might offer to suburbia.” Instead of addressing basic issues such as transportation, Open house tries to re-envision what it means to live within the suburb. By “creating jobs”, “encouraging social encounters”, and “playing a psychological role” (4), this project strategically attempts to alter the conditions which gave rise to such initial issues as long transit times, economically inefficient infrastructure, and social fragmentation (5). To respond to Allison Arieff’s question of “Can we discuss the future of suburbia (or the future of anything, really) without being critical?”, the answer that Open house responds with is clearly no, and creatively goes about this criticality in a projective, positivist manner. In order to investigate this form of criticality, it is important to first gloss over the existing context the project is deployed within and acting upon: the suburban ideology.

The platform of the 20th century American suburb is fundamentally based on individualism. Emerging as a response to the urban conditions of the Industrial revolution, the suburb employed the concepts of distance and property to facilitate the creation of an identity. Throughout the evolution of the suburban morphology, its potential for producing a ‘self’ in this sense diminished; as the suburb propagated the landscape, this element of difference literally dissipated. In response to this inherent characteristic of obsolescence the suburb evolved with scientific precision to exploit a commoditized logic of differentiation and continue facilitating this basic notion of the American dream. What we are currently left with is a highly idiomatic, highly complex landscape that is the context for over one half of American people and an even greater percentage of developed land. The basic existential conception of the self that the suburb so profoundly established is a core virtue that the Open house project attempts to reinstate; it highlights latent opportunities to fulfill our basic economic needs with alternative means of establishing community based on intersubjective exchange as opposed to mere commoditized identification.

Levittown, New York stands as a symbol for the suburb, and it is self-consciously polemical that the two firms worked within this village to initiate their project. As the prototype for the post-World War II suburb, it is subsequently a shared reality by a vast number of Americans today. While each house was originally built exactly the same for reasons of economic efficiency, the residents of Levittown were quick to realize the insufficiencies of this logic. Soon after they moved in, many began to modify their houses in order to better serve their specific needs. In fact, with the original inclusion of an ‘expansion attic’ integral to the house’s design, this process was both encouraged and expected (6). Being left explicitly unfinished, the home was literally a means for self-actualization. This relationship one has to their house has effectively disappeared as the modern evolution of the suburb surreptitiously abolished this potential by presenting the house as a finished product. As a semiotic commodity for identification itself, the house no longer possesses the propensity for acting as a medium towards defining one’s being. The plot sizes of Levittown are quite small, and so was the original house. Coupled with the population boom post-World War II, not only was this original element of customization to better serve the resident’s desires, but to address a basic need they had for growth. Throughout the later parts of the 20th century suburban houses grew larger with space itself becoming an incentive for new buyers, providing further opportunities for aesthetic and spatial customization to be integrated into the initial product of the house. As the suburban home became more of a commodity, the concrete relation the individual had to their house was largely negated. Necessity, once fundamental to the suburban zeitgeist, has effectively been taken care of by advanced industrial and capitalist processes. Open house is an attempt to re-engage this spirit under a different set of circumstances.

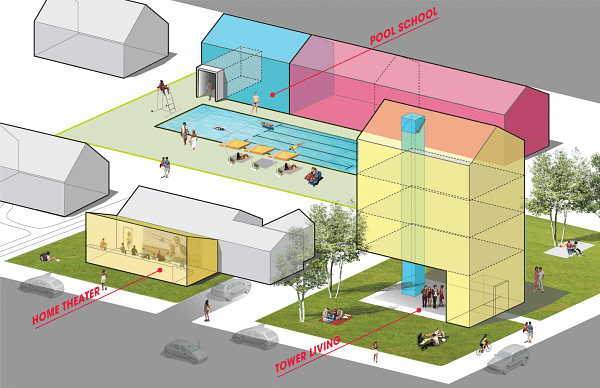

In more tangible terms, how does Droog & DS+R present what Open house actually is as a project, theoretically, to be realized? There is actually very little that the two firms propose themselves, and the closest we can get to a concrete proposal are sample floor plans by Droog and aerial visualizations by EFGH (Hayley Eber & Frank Gesualdi) with Irina Chernyakova. These graphics represent, in a sense, a utopia; a life with a different ideology, a different social, spatial, and economic relation to the environment. If this project can be seen as utopian, it is important to question its extremity as such. As it is presented, with simply a changed zoning law and some personal initiative (and maybe a bit of cash here and there), the suburban block can be transformed into a vibrant, almost street fair-like, atmosphere. By providing many services within and from the suburb, a sense of a communal environment can be experienced with its foundations in the interdependent relations between neighbors. Aside from the bureaucratic challenges this raises, it would be essential that the residents themselves not only will this situation into being, but would act towards producing the reality. How then does this project work to inspire the adoption of its ideology?

An array of tactics are employed to make this project highly communicable and convincing to a vast array of people, utilizing catchy yet deep slogans such as “DISCOVER YOUR INNER SERVICE PROVIDER”, attractive and simple graphics, and (a degree of) community engagement. But while the communicative means used to present the project are intriguing, there is an essential internal element of communication that threatens to compromise the integrity of the larger aims and potential success.

This new proposed model of suburban livelihood places a strong emphasis on the ability to communicate with our neighbors, simply to be aware of what potential services, communities, opportunities, lie within. If privacy is one of the basic elements of the suburban morphology, a question fundamentally asked by Open house is how do we open ourselves up? Sadly, there are only a few insights into this matter. The most literal and transparent response to this basic necessity of the project is Open house #7, ‘House of Signs’ by The Living. The service of this house is to make signs for everyone else in the neighborhood so that they can effectively represent themselves in this new context. Looking beyond the solution of making each building a decorated shed, Open house #2, ‘Block Pantry’ by Janette Kim and Erik Carver with Gabriel Fries- Briggs, unites service with a form of communication through rapid prototyping of common materials with symbolic and functional forms. A somewhat obvious response to this critique is the internet, but retaining an architectural method to the project, it cannot simply rely on using facebook in an arguably different way to achieve its vision.

While these two installations exemplify ways of addressing this constraint, the constraint itself is quite revealing under further inspection. By necessitating a level of personal advertisement for the success of this new environment, the capitalist process is integrated deeper into the functioning processes of the suburb, truly embedding it from within. This gesture dangerously teeters between ideological liberation and hegemonic enslavement: while presenting an opportunity for a heightened level of independence from the totalizing-yet-fragmented suburban environment, it also risks the further integration of such processes by making one’s entire being a spectacle (7). Ignoring these conceptual risks for a moment, I believe it is important to stress that the inherently interpersonal orientation of all such actions coupled with an economic disposition immanently grounds whatever the effects may be in the lived reality of our environment.

At this point the direction of my analysis can be made more explicit: how would it work? Beyond the critiques of communication, as they can be innovatively addressed with design, how would the reality proposed by Open house perform? In order to respond to this question further, the project’s fundamental vocation of becoming- capitalist is insightful. This foundation is explicitly owned up to when Charles Renfro states “Open house is an architectural outgrowth of a revolutionary re-adjustment of capitalist values, ones which mix with social values.” It is clear that the project intends to adapt the suburban environment to these ‘re-adjusted capitalist values’, and this requires primarily a re-adjustment of the self. What are the implications and consequences of this risk that would need to be subjectively willed upon by each resident?

To project in this manner the existing ideological context in which the project is intervening within must be explicated further. The suburban form is the reification of Marx’s critical object of estranged labor and alienation (8). Its inundation of space and total systematization of life has extensively constituted itself as our new nature based on the ideological principles stated before: distance, property, difference, and commodification. While Marx was theorizing about a struggle in which the connection between the laborer and his product is becoming lost, the contemporary suburban context is devoid of this struggle. As opposed to simply applying resistance to its consequences or searching for solutions to those immediate problems, Open house fundamentally accepts the current state of the suburb as a starting point to look for real solutions. Service is unique to a commodity based economy as service ties itself to a social element. It is partially these social products themselves that are produced by the new system of labor, which is evident in experience-based services such as storytelling, ping pong, or a listening ear. Open house has the capacity to negate basic suburban afflictions by fundamentally altering its context of economic, spatial, and interpersonal relations. By acting in an ideological manner, it provides an immediate framework with which we may conceive a new way to approach the challenges presented by our built environment.

1. Open House 2011 → Welcome to a Future Suburbia. Droog & Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Web. 13 May 2011.

2. Arieff, Allison. "Suburbia: What a Concept." New York Times (blog), 6 May 2011.

3. Ramakers, Renny. "Open House: What a Concept." Droog (blog).

4. Droog. Open House. Droog.

5. Pope, Albert. "Terminal Distribution." Architectural Design 78.1 (2008): 16-21. Print.

6. Hales, Peter Bacon. "Building Levittown: A Rudimentary Primer." Levittown: Building Levittown.

7. Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Trans. Ken Knabb. London: Rebel, 2005.

8. Marx, Karl. "Estranged Labour." Marxists Internet Archive.

Nick Axel is a graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy New York where he received a B.Arch degree with a minor in philosophy. Currently living and working in Madrid, Spain, he has previously worked in New York City and Santiago, Chile on projects ranging from urban planning and ...

2 Comments

Garage sales and lemonade stands should be given a large credit for this neo-liberal 'playing house' version of informal economies of shanties. The project is handled like a harmless card game. This informal styling is made 'fun times' in the much wealthier white suburbs. I had the same issues with some entries of Reburbia competition few years ago. It is inward.

Sticking to the "prototype" of the suburb in one way adheres and capitalizes on the idealist nature of the original suburban project, while in other ways says little to the hegemonic reification of its highly charged ideology. That said, the project is an attempt to truly subvert this situation by "working with, working against". Kind of brings into question the entire idea of 'subversion', no?

I think it would have been more successful in its reception, and also more effective (yet certainly not as attractive) if the firms took as their site something like a decaying immigrant suburb in the mid-west that is afflicted by crime and drug problems. Possibly one reason why they didn't do such a thing as that would be too specific, not as polemical, and not as 'interesting'. What we are left with is a chemical liquid and some litmus paper, but we dare not let them touch.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.