on the Metro Cable (cable car system), Santo Domingo Savio, Medellín (Colombia)

The

John K. Branner Traveling Fellowship,

awarded each year to three masters of architecture students in their

final year at the University of California, Berkeley, gives recipients

the opportunity to travel the world for twelve months in pursuit of

architectural inquiries that will later inform their theses. This

fellowship represents one of the most extensive pre-thesis travel

research grants awarded to master level students in the United States.

The 2010 Branner Fellows, Adriana Navarro-Sertich, Eleanor Pries, and

Melissa Smith have just returned from their travel and are in the midst

of thesis production.

Panoramic, Parque Biblioteca (Library Park) España in Santo Domingo Savio, Medellín (Colombia)

Social and cultural responsibility is returning to the forefront of

contemporary architecture. Although architects and planners have

addressed informal settlements, or favelas, for over sixty years,

it is only recently that there has been a shift in the paradigm.

Initially consisting of eradication and relocation, self-help and public

housing strategies, "slum upgrading" 1 has evolved to encompass strategies usually characterized as urban acupuncture,

aiming to minimize displacement while at the same time attempting to

better the conditions in the area. We are now witnessing spectacular

libraries in depressed neighborhoods, cable car systems in marginalized

areas, and museums in informal settlements. Following the long history

of tabula rasa schemes, and based on the foundation of Team 10 and urban

theorists and practitioners such as Castells, Perlman, and Turner, favelas

are no longer being vilified and viewed as cancers to cities and

society. Quite the opposite, through interventions that acknowledge and

legitimize informality’s architectural and urban potentials, designers

have begun to adopt the favela as a new paradigm, a paradigm I am calling Favela Chic. With design as a central component in configuring, Favela Chic interventions have accepted the notion "slums of hope," 2

viewing informal settlements as integral components in the growth and

development of the city, and thus reformulating the discourse of the

growing city, its configuration of built form and social activities, and

the relations between the global and informal.

Seeking to minimize displacement while at the same time integrate the favela

with the city, current interventions acknowledge auto-construction as a

legitimate way of providing housing, and instead focus on the aspects

that are absent in the settlement: infrastructure, public space and

public equipment. Although ranging in types and scales, from small

acupunctural projects to expansively designed infrastructural networks, I

have identified seven common architectural tools based on comparative

field studies in South America (Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, and

Venezuela): Plug-in Services, Urban Connectors, Icons, Skin+Sign, Dirty Works 3, Housing/Relocation, and Tectonic Uplift.

Favela Chic Tools

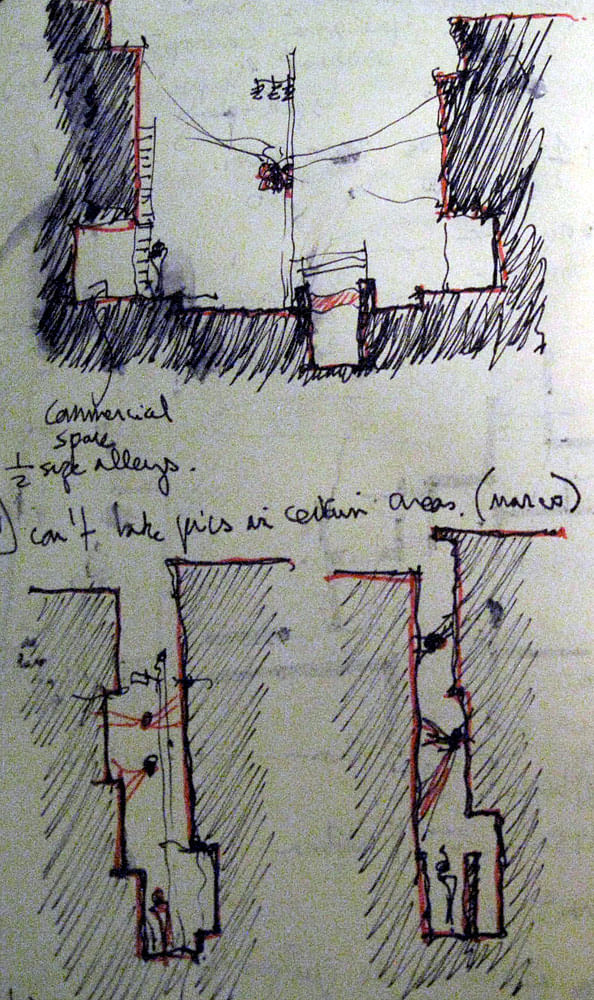

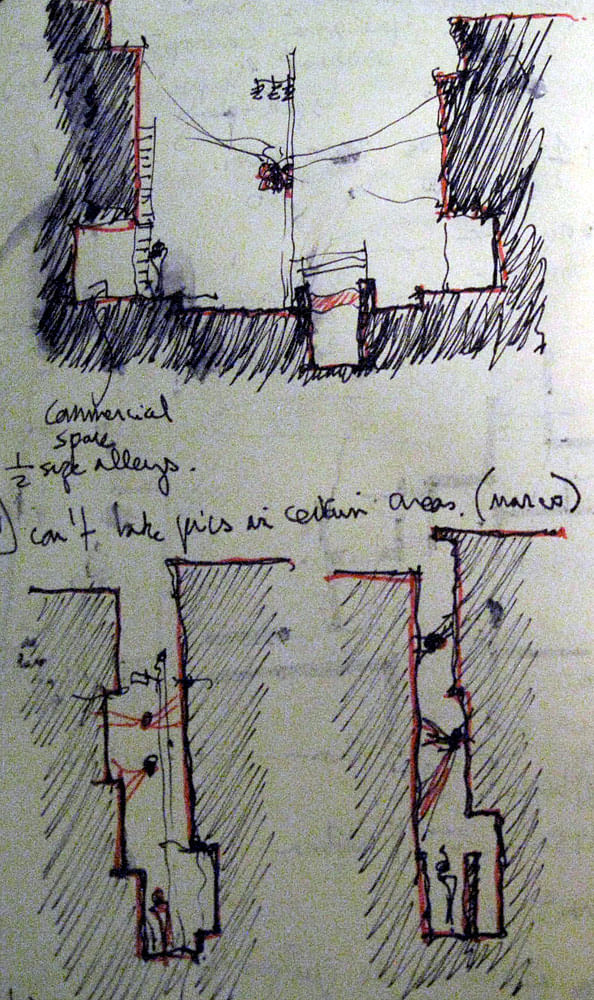

Plug-in Services: This tool focuses on improving basic services,

utilities and sanitation (electricity, water, black water treatment and

waste collection and recycling).

Existing conditions of infrastructure and electricity pirating, Rocinha Favela, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)

Section sketches of urban conditions in Rocinha Favela, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)

Urban Connectors: Focusing on access and mobility, Urban

Connectors include infrastructure of transportation systems (monorails,

elevators, cable cars) as well as circulation networks, such as transit

stations, paths, stairs and promenades.

Metro Cable in San Agustin, Caracas (Venezuela)

Waterfront and Boardwalk renovation project, "El Malecón Salado", Guayaquil (Ecuador). The "Malecón Salado" is part of the larger "Malecón 2000" beautification scheme for the city.

Icons/public equipment: These are formal markers and nodes within

the city (formal and informal). Consisting of mostly public programs

and interventions, this tool creates or reinforces the collective

identity of the area. Icons include museums, libraries, gymnasiums,

schools, kindergartens, and community centers.

Metro Cable and Library España in Santo Domingo Savio, Medellín (Colombia). Part of Medellín’s "Urbanismo Social" (Social Urbanism), the cable car and library are part of the Proyecto Urbano Integral (Urban Integral Project) in the Northeast of the city.

Skin + Sign: Aesthetics and imagery drive this tool. Focusing on

the application of paint, ornament and imagery to the exterior of

buildings and structures Skins + Signs attempts to beautify the existing

area.

Las Peñas and the Santa Ana Hill, Guayaquil (Ecuador). Las Peñas and the Santa Ana Hill were renovated as part of the "Malecón 2000" urban regeneration project in the city. The renovation consists the creation of paths and small plazas and overviews leading up the hill, but most importantly in the application of paint and restoration of building facades in the area.

Dirty Works: Dirty Works encompasses specific landscape designs

dealing with the sustainability of the ecosystem, including

reforestation, river restorations, land slide prevention and recreation

areas.

Creek restoration and ecological park Iporanga Favela, adjacent to the Guarapiranga water reservoir, Sao Paulo (Brazil)

Water restoration and boardwalk construction in Parque Royal Favela, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). This particular intervention took place during the first phases of the Favela-Bairro Program, one of the largest "slum upgrading" programs in the world.

Housing: Although Favela Chic interventions attempt to

minimize displacement, relocation is still essential, in order to

accommodate the interventions and manage risk areas. Whereas the

provision of housing is not the priority here, it remains a necessary

tool in the approach. In this regard, we primarily find mid-rise

structures, varying from in-situ and off-site projects.

Pre-fabricated Housing Structure in Heliopolis Favela, Sao Paulo (Brazil)

- Tectonic Uplift: This tool

involves technical assistance, as well as structural enhancement or

adoptions applied to existing or new constructions. Tectonic Uplift is

not as prevalent on a larger scale and appears to not be an integral

part of Favela Chic interventions; nevertheless, there are still some noticeable examples, including support and infill strategies. 4

"Manufactured sites" by Teddy Cruz, Border of San Diego (USA) and Tijuana (Mexico); source: www.moma.org

Even though many of these interventions are so recent that their real

impact is not yet discernable, conversations about key issues and

questions, as well as short- and long-term outcomes of the interventions

are critical to further the discourse and practice:

How are these interventions operating? What is the context and

framework, in which projects are planned, executed and maintained? Currently, some of the most interesting efforts to address favelas

are exemplified in Latin America. Significant reasons for this include

the political and economic dynamics taking place in the region, where

economic growth, decentralization and democratization processes have

allowed stronger local autonomy in urban development projects and

emphasized a desire to reflect citizen rights through city form. Some

key factors to acknowledge within the framework include:

- Local conditions (history, demography, geography/topography, geology and climate),

- Actors (independent professional/architect, state government, local government, NGO, multilateral agency, community)

- Funding (public sector, private sector, private-public partnerships, NGOs, multilateral agencies)

- Government

structure, programs + policy (centralized vs. decentralized, national

vs. local, top-down vs. bottom-up, levels of institutionalization, etc.)

- Regulatory and legal processes (including zoning and tenure)

- Precedents + Models (past and present theories and practices)

Where

exactly are these interventions operating, in other words, what defines

a non-formal settlement, or informality in a specific context? The

definition of informality is extremely contextual and dependent on

place. I would argue that there is not only one type of "informality"

but various "informalities," surpassing generalization of geography

(First and Third World, periphery and core, etc.), poverty, inequality,

illegality, marginality, isolation, nor resistance. Informality is not a

product but a process, constantly in the making, shifting and

redefining relationships (in may cases dependent and essential) with the

"formal".

5

Contingent on this, the strategies, morphology, spatial organization,

aesthetics, structure, and uses emerge from the constraints and

limitations of the formal system, or asfalto, and as such should be

understood in parallel to it.

Will projects be received and used in the same manner in different

areas and situations? When we speak of use, we also speak of associated

socio-economic outcomes. For example, will the impact of a Metro Cable in Caracas or Medellin be the same in other places?

Cultural specificities, in addition to the politics of place with its

particular socio-economic dynamics, set up very different conditions and

value systems that are embedded within the urban fabric. Although

physical challenges might be similar from place to place, the manner in

which these challenges are addressed needs to be very specific to

context.

What defines integration and what is the real impact of these

interventions? What are the structural limitations of a purely physical

intervention? What does it mean to insert a formal intervention in a

non-formal city? Are these long-term sustainable solutions?

As the

Favela Chic paradigm gains traction, we, as responsible

architects and planners, need to analyze the economic, cultural, social

and political implications of these formal physical interventions in

informal settlements, particularly as they tie into larger, global

systems. We need to understand and evaluate the impact and use value of

our strategies and interventions to avoid falling for the danger of

adopting an image of social good instead of addressing the social and

economic realities of everyday life.

Footnotes1 UN Habitat, Slum Upgrading Facility.

http://www.unhabitat.org/categories.asp?catid=542

A slum, as defined by the United Nations agency UN-HABITAT, is

"characterized by overcrowding, poor or informal housing, inadequate

access to safe water and sanitation, and insecurity of tenure." The term

"slum" is too freely used as a term to group all squatter and informal

settlements. Although slums are usually informal settlements, not all

informal settlements are "slums". In this same respect, informality is

not necessarily equivalent to squatting. This generalized definition of

"slum", also adopted by Mike Davis in "Planet of Slums" (2006),

homogenizes and stigmatizes all non-formal shelter practices. The urban

poor now have to deal with another form of social exclusion and many of

these working and living neighborhoods, and communities, are reduced to

eviction and demolition.

2 Contrary to the recent point of view provided by Mike

Davis’ "Planet of Slums," Perlman has long argued that urban residents

labeled as "marginal" are not in fact disenfranchised form the city but

are very much part of urban society contributing to the formal economy

and continuously striving to improve their lives. Perlman, Janice, "Six

Misconceptions about Squatter Settlements," in

Development, Journal of the Society for International --Development, l986: 4, pp. 40-44.

3 The naming for the tool ‘dirty works’ was taken from the

GSD landscape architecture exhibit. Beardsley, John and Werthmann

Christian,

Dirty Work Exhibition, Harvard Design School February 2008

4 John Habraken and SAR (The Dutch Foundation for

Architectural Research) have, throughout the last three decades,

influenced the design and production of alternative forms of mass

housing. Habraken’s "supports", deal with the infrastructure and the

provision of services- "infill"- which deals with the plan layout and

possibility for expansion, leaving room for to the accommodation and

experimentation of the dweller. Habraken, John,

Supports: An Alternative to mass housing, and

The Structure of the Ordinary: form and control in the built environment.

5 Castells, Manuel and Alejandro Portes, "World Underneath:

The Origins, Dynamics, and Effects of the Informal Economy" in Alejandro

Portes, Manuel Castells, and Lauren A. Benton, Eds.,

The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Advanced Developed Countries. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Adriana Navarro-Sertich

Adriana is in her fourth year of a dual Masters degree in Architecture,

and City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. Born and raised in

Colombia (S.A), she received a BS Arch (Honors) from the University of

Virginia in 2004. Adriana worked for Rafael Viñoly Architects in NYC, as

well as SORG, and OPX Global in Washington DC before moving to

California for her Masters degree in 2007. At the University, she has

taught entry levels studios and has been a Research Assistant for

various professors. Throughout her studies and practice, Adriana has

primarily focused on the socio-cultural aspects of design, specifically

analyzing the relationship between architecture, planning and

informality. More information on the research, cities and projects

related to

Favela Chic can be found in the blog Adriana maintains:

www.FAVELissues.com

1 Comment

Given your titles I would be curious to know what you think of writer Bruce Sterling's coinage of the phrase Favela Chic, Gothic High Tech, to describe the contemporary global condition. He discusses in this video here.

Obviously he is not foucsed on design/architecture per se, but still the phrase highlights a useful tension, even amongst the design professions I think.

Moreover your passage For example, will the impact of a Metro Cable in Caracas or Medellin be the same in other places? i think gets at a key question. In the BIG Pink Book the term glocal is used. This phrase while not new has been used to indicate the need for localized solutions to global programs, and the need for global awareness directed at the local level. Your passage highlighted above seems to imply the same. The kit of tools is perhaps the same. But the specific application needs to be tailored to the specific contexts (political, social, economic etc) of the place.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.