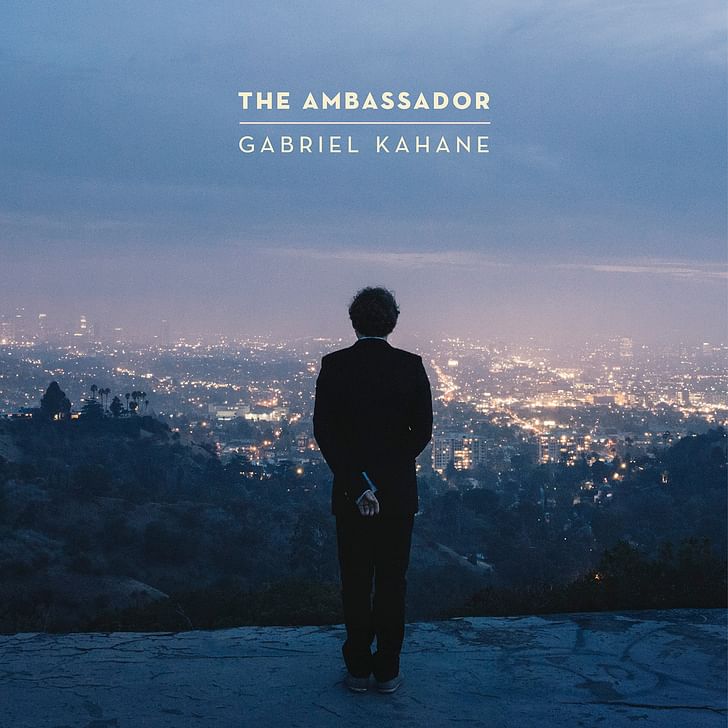

Gabriel Kahane's new album, The Ambassador, builds songs from the moods of places within Los Angeles. Born in Venice Beach, raised in northern California and living in Brooklyn, Kahane has created an unlikely ambassador for Los Angeles' pathos.

Los Angeles is currently in the midst of June Gloom, an annual meteorological phenomenon that blankets the basin in hazy, low-hanging clouds from the ocean, until they’re burned away by the early summer’s sun. For a city so enraptured with its own solar iconography, you’d think Angelenos would despise June Gloom, but we stoically take it on the chin, as a burden we all must bravely bear to live in such a paradise. Usually, the clouds disappear before noon.

Indeed Los Angeles is a city often represented through its weathers -- yes, plural. Joan Didion’s Santa Ana winds, Mike Davis’ catastrophic fires, a conglomeration of heat islands and sea breezy bungalows, a fantasy-land of orange groves and open asphalt. Their accounts occupy the slight disparities in what we think of as the monoliths of Los Angeles, adding caveats to icons and relishing the contradictions.

This attitude is a large part of The Ambassador, the new baroque-folk-pop album on Los Angeles from singer-songwriter Gabriel Kahane. The liner notes for the album are written by Christopher Hawthorne, architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times’, who cheekily headlines sections of his notes with contradictory truisms on LA — it does and doesn’t have a center, the cliches are all true and all false — and aligns their frictions with Kahane’s songs. Each track is titled with a specific street address somewhere in Los Angeles, and crafts a personal history (not Kahane’s, for the most part) related to that place. Altogether, the album is a folk history, happily non-encyclopedic and emotional, with visions of noir, apocalypse, riots, and endearment amongst the contradictions.

Kahane spoke with me about becoming an amateur historian for the album, and his growing empathy for Los Angeles as it continues to change.

Amelia Taylor-Hochberg: First, I'd like to discuss the background research that went into this album. What was your approach, what information were you looking for, and what was motivating you to do research?

Gabriel Kahane: This project had it's earliest embryonic existence in 2007 when, for the first time I spent a significant amount of time in Los Angeles as an adult. I was working on a musical theater piece for Center Theater Group. And I had sort of inherited the dogmatic antipathy for LA, both as a New Yorker and also having spent my teenage years in Northern California, I was kind of doubly primed to hate LA. And when I started spending time there, at a moment of great personal post-adolescent heartbreak, I found myself increasingly in touch with the pathos of the city. I was reading Joan Didion for the first time, reading Mike Davis for the first time, and started to see beneath the sunny veneer of the city, and to initially fall in love with it. I think it was in 2011… by this point I had grown to really love LA, and was always grateful when I had an excuse to head out there. There was this particular drive I took from the East Side to LAX, very early in the morning by surface roads. And driving through Inglewood I just found myself moved almost to tears by the ache of the city, and I had this offer to write an evening-length piece for the Brooklyn Academy of Music (for their Next Wave festival, which is going to premiere this fall, first at UNC then at BAM, then at UCLA in February). And I was thinking about something that would have a visual component to it, and I thought, "well, maybe this is the time to do something about Los Angeles." And then right around the same time, Sony Masterworks approached me about making records for them, so I decided to kill two birds with one stone and do this exploration of Los Angeles that would be both an album and a stage piece.

what are the stories that are contained in buildings, and what are the emotional relationships that we have to structures?And as I started to think more about Los Angeles, trying to get to the bottom of why this ache of the city presented itself to me in such a strong way, I found myself increasingly drawn to architecture and in particular, residential architecture, and then sort of formulated this (perhaps obvious) binary formulation. That there are two Los Angeles: there is the mythological LA — the LA of film and of television and of fiction, the aesthetic LA. And I don't in any way mean a superficial LA, but in a very specific way an LA that is an aesthetic projection. And on the other hand, you have this incredibly vulnerable physical city — the city that burns, that's prone to earthquakes, the city of the Santa Ana winds. It appeared to me that architecture sits at the intersection of those two LA's, because architecture as a mythology is an aesthetic projection, and also buildings burn and they crumble in earthquakes, or I guess we hope that they don't but they do, sometimes. That sort of provided the excuse to make this inquiry about LA through the lens of architecture, or if not architecture, through place, and stories that inhabit these places.

So the research really took the form of a great deal of reading. Reading that ranged from James M. Cain to Raymond Chandler to Mike Davis to Carey McWilliams, to reading all of Christopher Hawthorne's pieces, and actually spending some time with Christopher who I know a little bit. And then watching a ton of LA films. I think Tom Anderson's film, Los Angeles Plays Itself, was a kind of filmography for the project. I just transcribed the names of all the films that he made reference to and tried to watch as many of them as I could. And then I spent a lot of time driving around, walking around, and just trying to find the places that spoke to me. In some instances, the address preceded the story, which is to say that I had an emotional response to a building, like say Union Station or the Schindler House at Kings Road (for which I wrote a song that didn't end up on the album). In other cases there were moments, either historical moments or moments in fiction or in popular culture, that I knew that I wanted to write about, and shoehorned them into an address that made some amount of sense.

I very much like the idea of architecture at the intersection of pressing danger, of economic or natural meltdown, and aesthetic mythology. To me, a lot of contemporary discourse about Los Angeles architecture has far much more to do with the post-70s aftermath of SCI-Arc, and talking about LA as a developmental platform. But I think these conversations are fascinating because of the girth of LA, it's so huge, and borders can be disputed. The Ambassador has its own built-in map, the Ambassador Atlas, that labels all of the locations featured in the songs. Did your idea of LA have particular borders that you were going to stick within, or were you going solely on emotional response, when choosing these destinations?

Over the last couple years in a general sense, not strictly related to The Ambassador, I've come to believe that when art attempts to be encyclopedic, it almost invariably fails. To that end, there were a lot of somewhat arbitrary and almost chance decisions as far as what I was responding to and what I was choosing to write about. Obviously, the West Side is almost completely neglected in The Ambassador. There are ten other songs that I wrote that, for various reasons, didn't make it onto the album, some of which will be incorporated into the stage version. But playing off of this idea of the danger of attempting to be comprehensive: I don't think that I was thinking in any circumscribed way about either the limits of Los Angeles or the need to include certain things because they're particularly iconic. It was really very intuitive, as I think a lot of research-based things that I do are, particularly things that are sprawling. An earlier project, Gabriel's Guide to the 48 States, was a tour of the country through the text from the WPA American Guide Series. There again there was an instance where if I tried to be encyclopedic, the piece would have been thirty hours long, and everyone would have died in their seats. I was initially working from a kind of emotional impulse, and that I think that emotional impulse gave way to a critical inquiry of why does this place make me feel the way that it does? And that led down various rabbit holes of, what is behind the Schindler/Neutra rift?You can't really get into trouble with writing about the future because it hasn't happened yet.

I had a really interesting encounter when I played at this event, a conversation between Christopher Hawthorne and Mayor Eric Garcetti, where an older gentleman came up to me after the event and said, I recognize the address from the Villains song, of course it's the Lovell Health House. And he told me this story about having met, many many decades earlier, Neutra at some cocktail party. Neutra lamenting the fact, saying I can't get a photo of that damn house anymore. And this gentleman happened to know some vista from which one could get a photograph of the Lovell Health House. And to me, the fact that Neutra was thinking about how the house looks, from the exterior, to me, from my in no way expert vantage point, is a great distillation of what presents itself as the great divide in their attitudes about architecture. I think of Schindler and the Kings Road House, while it may have been thoroughly impractical as a place to live, the way that it articulates space and the way that he thought about materials, the way that he really moves away not just from ornamentation, but even the idea that the materials should be beautiful, but that they should articulate space beautifully, is something I've found so moving and when I think about the two of them coming apart and Neutra stabbing Schindler in the back, I think I come down sentimentally on Schindler's side.

I think that also connects back to Tom Anderson's film and the question of why do villains always live in houses built by modernist masters, and one could make the argument that Neutra himself was somewhat of a villain, and the austerity of some of those structures does border on a kind of pathological … there's something clinical there. Whereas I find when I walk around the house at Kings Road, there's just this tremendous warmth there. I don't think you see Hollywood directors putting people in Schindler House, maybe the Lovell Beach House, but certainly not Kings Road, which to me is such a model of beautiful communalism.

I imagine that while touring The Ambassador, it wouldn't be uncommon for people to share their own ideas about Los Angeles and experiences at the tracks' locations.

In fact last night a young woman who I know came up to me in New York and said, "I had completely forgotten this but my grandfather was a marble worker, and he participated in the building of Union Station." Making those kind of connections. There was a family friend who wrote me an incredibly tragic story. He had lived in Los Angeles for many years, and had a tradition of going to Musso and Frank for flannel cakes, and he said he had this particular relationship with this wonderful waiter who had come from Mexico and who was a Dodgers' fan, and whose son was beginning to play Little League, and one day he was found murdered outside of Musso and Frank. And this family friend said they never went back. As horrible as that story is, there is something about the way that this album is beginning to function in a very limited way, in unearthing people's relationships to these places. I remember also when Renee Montagne interviewed me for NPR, she was really excited to talk about Musso and Frank, because she had her first Manhattan there. Things like that. I think that's always been a preoccupation of mine, what are the stories that are contained in buildings, and what are the emotional relationships that we have to structures?

I think it will be interesting for the younger subset of people that are listening to this album, and hear the Bradbury song and its reference to Blade Runner, because even though I grew up in Los Angeles, I still have the strongest relationship with the Bradbury building through that movie, and not reality. In that cultural sandstorm that takes place around these buildings, I think more and more you'll start hearing people telling you their stories through other media associations. It's not "I remember the first time I went to Griffith Observatory," it's "I remember the first time I saw Rebel Without A Cause." And even though the titles of these tracks all refer to a specific place, each track also has its own character perspective, at least in my listening. I wanted to hear about how you organized the lyricism of each individual track, and whether you wrote with characters in mind. How did you approach the opportunity to build characters into these songs?

To respond as a side note to your comment about the Bradbury song: I actually didn't see Blade Runner until early last year, when I was starting to do research on this record. I think that might be a generational thing or just my relationship to film, having become interested in film later in life. But in the same way that I, as a teenager, sometimes got to know popular songs either from the American songbook, or through jazz artists (weirdly my introduction to Radiohead was really through Brad Mehldau, jazz pianist). I think that there are these circuitous paths that people take to having relationship with things in popular culture. I love the idea that people who are, say, teenagers or college students now, might listen to the Bradbury song, get curious to go back and see Blade Runner. That would be very gratifying to me, if people of that generation developed relationships to the things in popular culture that inspired these songs, as a result of the record.

But to speak to your question about character: I think, and I'm not being glib, but I'm more and more bored with myself as a subject. Milan Kundera talks about "the lyrical age": the moment in the artist's life when he or she is only able to look inward, and that, god-willing, the artist graduates from the lyrical age, and is able to look out. Kundera takes a view that the problem with poets is that they never graduate from the lyrical age, that they remain perpetually narcissistic and inward looking. I think for me, the tumult of my 20s is done, and I'm much more interested in trying to get inside the mind of a character, either one invented or a historical figure. There wasn't really any strong organizing principle for how these characters relate to one another.

One relationship that did strike me while I was working on the record was, weirdly, the connection between Latasha Harlins and the Kennedy family. In the sense that they're these two families, incredibly tragedy prone. I'm thinking specifically of the Robert Lowell poem written after Kennedy's assassination, which I paraphrase badly in the title track, with "doom was woven in his shirt." Reading about Latasha Harlins, I got the sense that her death was almost pre-ordained. Her mother and uncle had both been killed on the same Thanksgiving Day when she was five years old. There was almost this magnetic relationship to violence. Thinking about the Harlins family, that struggled so much and that represented the classic westward aspirational move for a better life, and of course what resulted was just tragedy upon tragedy. And then thinking of the Kennedys, this golden American, patrician family, and yet this same propensity for tragedy. There's something about that that spoke to me. I guess that's probably the closest that I got to thinking of relationships between the characters.

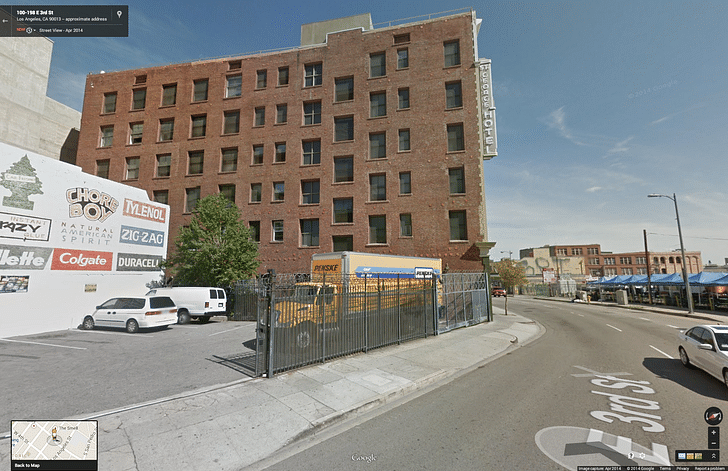

In the case of Blade Runner, and the Bradbury Building, it just seemed like an interesting exercise to try to make this composite, replicant character, sing as a robot. In the case of the track "Slumlord Crocodile", I had been reading Mike Davis' book, The Ecology of Fear, and in particular the chapter which I think is called "The Case for Letting Malibu Burn". Of course it's a very academic and polemical, Marxist argument, highlighting the absurdity of the changes to FEMA in the mid-90s, requiring cuts in social spending that offset any disaster relief FEMA was doing — such that (according to Mike Davis, who frequently needs to be fact-checked), Richard Gere's home (having been burnt down in the Malibu fire), is then rebuilt through cuts to social spending. And then at the same time, the horrific hotel fires of the St. George, the titular address at 115 E. 3rd Street. Looking at the way Davis argues that there's this connection — sort of like Harlins and Kennedys — that across a huge socioeconomic chasm there is this unity in dealing with catastrophic fire. And of course this is highly academic, and I really wanted to do a song about this that wasn't going to be boring and inaccessibly discursive. So I started reading about arson and that led to the idea of this character; a sort of creepy arson dude, who wants to impress his lady by burning shit down. So that's where that song came from. And really, every song has a different "in", and the dedications that appear in the lyrics sheet are there to provide context for people who are coming to Los Angeles and LA culture from the outside. It's a little bit of a treasure hunt on purpose. And I think "Bradbury" and "Union Station" are maybe versions of me as the narrator, but still with a lot of fictional detail in "Union Station" (because it's post-apocalyptic, after the second coming of Noah's flood). I quote in the first and last song from an older song I wrote called "LA", which was on my last record, and the quoting was intentional but the fact that they became the bookends for the record was sort of an accident.

The most recent historical reference in the album is to the death of Latasha Harlins in 1991, with "Empire Liquor Mart." The folk history that's being put together in the album isn't about trying to communicate a comprehensive LA, or even a single image of what LA presently is, no matter how convoluted and contradictory that may be. Did you have people in mind that you wanted provoke, or make a particular impression on, when making this album about Los Angeles?

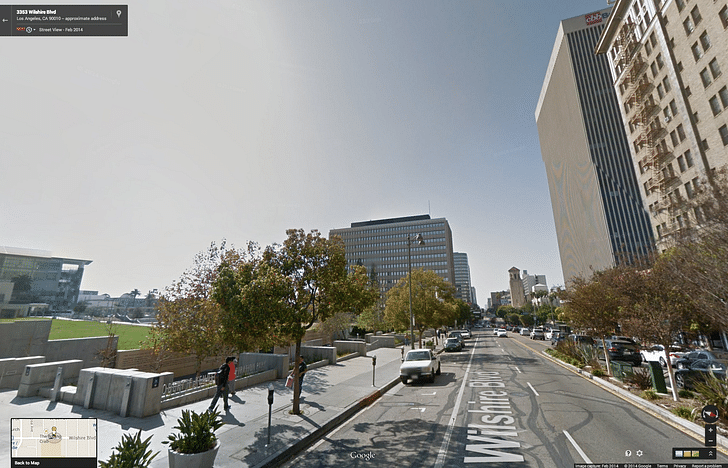

I wanted to start with your comment about time, which was absolutely deliberate — to not go beyond the riots. But also to deal with the future. I think for me, that has to do with the fact that when you read literature on Los Angeles, the city is so much in flux that by the time anything is published, it's already dated. I think there is huge value, obviously, in reading some of these histories or these studies. I'm thinking of Reyner Banham and Mike Davis, as a sort of portrait of the city at a particular time. But in as much as this album does relate to theater, because it is also going to be a theater piece, I've always had misgivings regarding theater pieces trying to be hyper-contemporary. I think I'm more interested in art that either looks at the present through the lens of the past, or looks at the present through a projection of the future. If I were to reveal my ideological stance about LA, I think what's going on in LA right now is so extraordinary, and I have so much admiration for what Garcetti is up to. I feel there's this incredible optimism following so many decades of folly, vis-à-vis transit and so on. I think the Great Streets Initiative, while ambitious and maybe quixotic, when you read literature on Los Angeles, the city is so much in flux that by the time anything is published, it's already dated.seems really really amazing, and hearing Garcetti speak back in February with Chris Hawthorne, I found profoundly inspiring. And so on the one hand, I can see that a certain Angeleno might find my cut-off date of 1992 as being sort of unfair. But I think it's really more that, as a historian (if I'm functioning as an amateur historian in this record), I feel like I can't really go any further than that, and still really understand and have a perspective on where this city is.

I feel like the flux in the last ten years, just the way that downtown has become so utterly transformed, even in the last five years, I didn't want to get into a situation of making some kind of assessment and having this record exist as a sort of dated document. In an attempt at the record for posterity, I think that's why I wanted to end there. I think also, thinking about Mike Davis and City of Quartz, that if you were to be really reductive, you could make the argument that that book has become so totemic, because it was so prescient. He knew the boiling point was there and that the shit was going to hit the fan, and then it did. So I think that 1992 is a really interesting place to set the limit as a particularly interesting boiling point. I think there will be many more to come. You can't really get into trouble with writing about the future because it hasn't happened yet.

To answer your question about audiences, I've been really pleased initially. I was really nervous that being an interloper, that Angelenos would find a lot of this really obvious and silly, or stupid. And in general, it seems that people who live in LA are not only not offended by what I'm trying to do, but are getting the sense that I have deep affection for the city. But I think that first and foremost, I am trying to function a little bit, in a humble way, as an ambassador for Los Angeles, from the outside. And that's part of the title, it refers both to the hotel and also this idea of wanting to show Los Angeles in a different way, that is not strictly the glitter and the glitz of the Industry. To really shed light on the ninety percent of the people and the lives that have nothing to do with television. Who are aspirational in another way, a much more modest way, trying to keep a roof over their heads and feed their families, and the energy behind all of that.

The Ambassador was released June 3, and is available on iTunes.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

Good interview, enjoyed the read. Checking out the sounds now.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.