“Again we decree that the monasteries which are to be built shall be built as humbly as possible, from mud and twigs, or from rock and clay where twigs cannot be had easily… We also decree (…) that absolutely all vanity, superfluity and precious things of gold, silver, silk or velvet shall be banished from our churches…“ Capuchin Statutes of Albacina (1529)

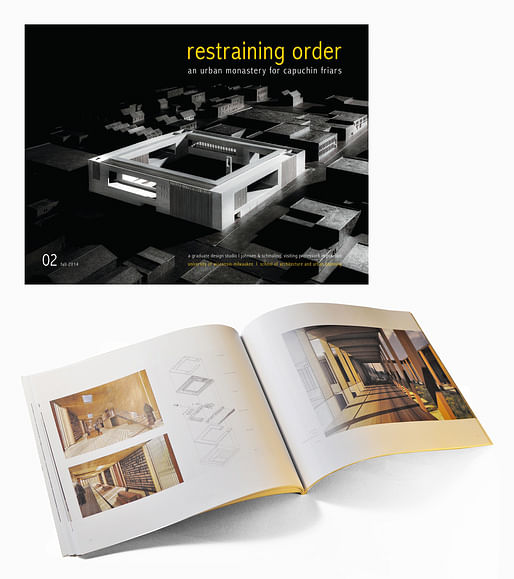

This guest post by Brian Johnsen and Sebastian Schmaling [johnsenschmaling.com], Professors in Practice at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, documents the work produced in the fall of 2014 by a group of 15 graduate students at the School of Architecture & Urban Planning. The studio, “Restraining Order,” focused on the design of a monastery complex for Capuchin Franciscan friars in Milwaukee’s central city. The title alludes to the radical simplicity, austerity, and restraint governing the life of a Capuchin friar – a life dedicated to serving those in need: the poor, the sick, and the socially marginalized. The 500-year-old Order of Capuchin Friars Minor arrived in the United States in 1857, when two Swiss friars established the first American Province of Capuchins in Milwaukee, starting a legacy of social engagement that continues to this day. Currently, Capuchins in Milwaukee are busy running one of the city’s largest soup kitchens, collaborating with UWM nursing students to provide basic healthcare for the poor, and offering emergency shelter for the homeless.

It is the Capuchin ethos of frugality and restraint that guided our semester-long design investigations, exploring the possibilities embedded in an architecture of profound and unapologetic simplicity. From the outset, the concept of frugality had a profound impact on the design of Capuchin buildings. At a time when churches were expected to be built from stone and feature elaborate décor both inside and on the outside, the Holy See made an exception and permitted the Capuchins to build simple buildings from wood, a material customarily deemed too mundane and too provisional to adequately represent the Divine.

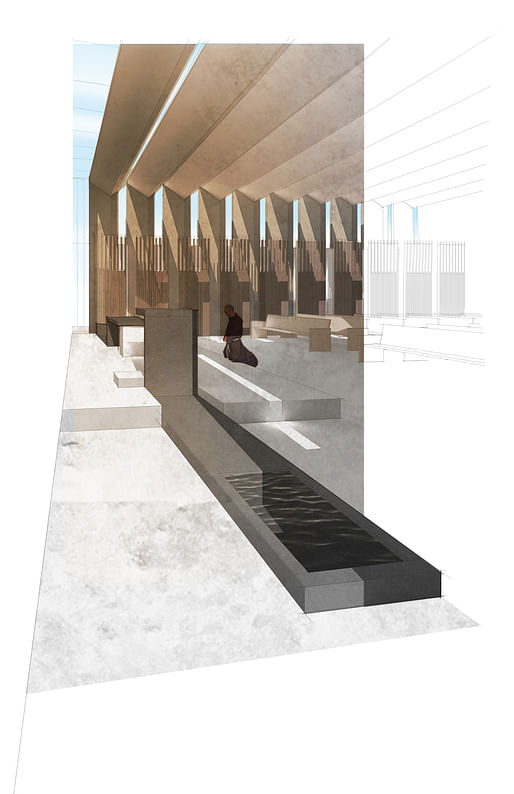

Our conceptual explorations of architectural simplicity and restraint focused on the use of wood and concrete, arguably today’s equivalents to the “mud and twigs” that the Capuchin’s had formally declared the preferred material palette as early as 1529. We paid particular attention to the rapidly evolving field of contemporary wood construction, continuing a research agenda that we initiated in the fall of 2013.

Students were challenged to develop meaningful architectural strategies at all scales that exploited the conceptual richness of seemingly archaic topics such as silence, solitude, humility, and spirituality – all fundamental humanistic concerns increasingly marginalized in a world hungry for perpetual entertainment and instant gratification.

Monasteries tend to be more than single, monolithic buildings, instead combining different typologies and programmatic elements into complex ensembles that organize the daily lives of their inhabitants and offer them housing, work, food, education and, arguably, even entertainment. As quasi-urban microcosms, their architecture reconciles and transcends seemingly contradictory objectives and values, mediating between the individual and the collective, between the need for spatial separation and the desire to facilitate communal life, between self-sufficiency and inter-dependency.

The proposed urban Capuchin monastery complex in Milwaukee may be unprecedented in terms of its urban setting, program and overall scope, but it inevitably becomes an extension of the rich trajectory of Christian monastic architecture that spans nearly two millennia, making the study of historic and contemporary precedents a prerequisite for any meaningful design explorations. Students were asked to study a number of architecturally significant monasteries, focusing on their roles as archetypes of “hybrid buildings” – structures that house diverse, sometimes even competing mixes of programs and uses. Precedents included paradigmatic historic projects such as Le Thoronet, a 12th century Cistercian monastery and Elias Bombarone’s San Francesco in Assisi; 20th century examples by van der Laan, Breuer and Le Corbusier; and lesser known contemporary buildings such as Tautra Mariakloster in Norway by Jensen & Skodvin and Knotopher Friary in Ireland by ODOS Architects.

Our research of monastic architecture were intended to be an analytical and interpretative exercise rather than a comprehensive historic or anthropological survey of monastic architecture; the objective was to identify and understand both formal and conceptual frameworks that have shaped the design of monasteries – unique and reoccurring ordering principles, both immaterial and concrete, that may inform the our own design agendas. Students were asked to concisely decode the main characteristics of each project, highlighting the general contextual, volumetric, infrastructural, circulatory, spatial, and organizational strategies that were employed in its design and translating the findings into a comprehensive narrative that conveys the precedent’s essential architectural and ideological framework.

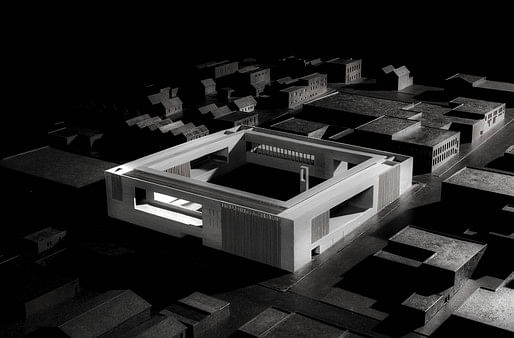

The proposed Capuchin monastery will occupy an entire city block on Milwaukee’s South Side, a dense urban area with a sizable Hispanic and predominantly Catholic population. Mirroring the economic challenges facing many of Milwaukee’s central city neighborhoods, the area suffers from disproportionately high rates of unemployment and poverty as well as from a lack of healthcare facilities and other social services. The site is located at the threshold between the Menomonee Valley and the Walker’s Point neighborhood, bordered by S. 11th, S. 12th, W. Bruce and W. Pierce Streets, and sandwiched between the Burnham Canal to the north and National Avenue, an important east-west thoroughfare, to the south.

Following decades of modernism’s radical rejection of context as a legitimate architectural concern, the revisionists of postmodernism resurrected the urban context as a legitimate architectural concern, but their ideological agenda was quickly hijacked and commodified by profit-seeking developers and corporate design sweatshops who turned the renewed interest in contextuality and place-specificity into cheap, historicist, and easily digestible copy-cat architecture, highly marketable but void of any meaning. While today, the concept of “contextual design” has largely been reduced to an exercise in stylistic sugarcoating, we continue to believe that it is imperative that we properly decode and intimately understand the context in which we operate – the existing geographical, infrastructural, ecological, social and cultural landscape that impact our architecture (or might be affected by it).

This analytical approach transcends the simple mapping of the physical realities of a site. In addition to the collection of geographical data and traditional mapping techniques (topographic surveys; figure-ground plans; circulation maps; solar studies; etc.), a meaningful site analysis requires an interpretative reading of the forces that have shaped and continue to shape a particular locale over time, revealing those unique characteristics and idiosyncrasies – physical or immaterial; visible or invisible; obvious or elusive – that imbue a place with its genius loci, its distinctive atmosphere and particular flavor. Students were challenged to deliberately select specific thematic lenses for their investigations and to analyze and explore the site at all relevant scales – the scale of the region, the scale of the surrounding neighborhood, and the scale of the urban block itself – simultaneously considering the site’s extents and constraints, scrutinizing its existing and speculative properties, and searching for and interpreting the physical and ideological forces that have shaped it, all with the goal to reveal a unique and relevant genetic pool for their own projects.

Capuchin friars maintain a robust presence in Milwaukee to this day, but their current facilities are geographically limited to the north-east corner of downtown. The proposed monastery on Milwaukee’s South Side will allow the order to reach out to the area’s largely underserved minority and immigrant populations, providing critical social services and filling the current void of appropriate facilities or a functioning public welfare system.

The new monastery complex will include a friary for 32 brothers and their guests; a church; a soup kitchen and food pantry; a small health clinic staffed by volunteer doctors; a small homeless shelter; and structured parking for 15 cars. Building will occupy only 50 percent of the site; the remaining open space will be used as a vegetable garden and orchard as well as a cemetery for deceased brothers. Four distinctive but interrelated design paradigms guided our design investigations:

holism: site design, building design, and landscape design must be developed in tandem, following a comprehensive design strategy to create a monastery complex that becomes an integral part of the surrounding area and neighborhood fabric.

functionality: the monastery and its different parts shall be organized in a manner that takes advantage of the existing typological and topographic context. All program components of the monastery shall be organized on the site in a way that allows them to function both individually and as a whole.

public presence and visibility: the monastery shall have a robust visual presence in the neighborhood, a beacon of hope in both physical and spiritual terms.

materiality: wood and wood-based hybrid products must be the primary construction materials for both structure and building envelope, complemented only by cast-in-place concrete. The building is expected to become a case study in the innovative use of wood in contemporary architecture and a case showcase of recent advancements in timber technology

Students were encouraged to employ a non-linear design approach where the focus of attention continually oscillates between overall concept, program, structure, and envelope, all of which need to be developed simultaneously and adjusted constantly. Particular emphasis was put on the development of convincing tectonic concepts, the integrity of each project’s materiality, and the care with which its components were assembled and joined, an iterative process that required a continuous critical re-examination of previous design decisions and demanded a constant shift between scales in order to ensure consistency between all aspects of the projects to avoid design decisions made in a vacuum without understanding the ramifications for the overall building.

The work from this studio is now available in book format, published by the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee.

Each semester, SARUP turns into a beehive of creative activity, with the collective energy of students and faculty resulting in projects and presentations that excite and intrigue, as they generate enquiry into the disciplines of architecture and urban planning. This blog is an attempt to give a glimpse of our life.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.