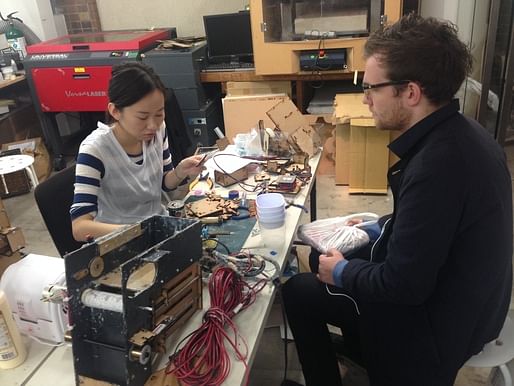

After our break in September, we resumed work on the project, with the help of graduate students new to the lab. We worked in four basic teams, which were somewhat fluid, but helped us structure the direction of the various activities.

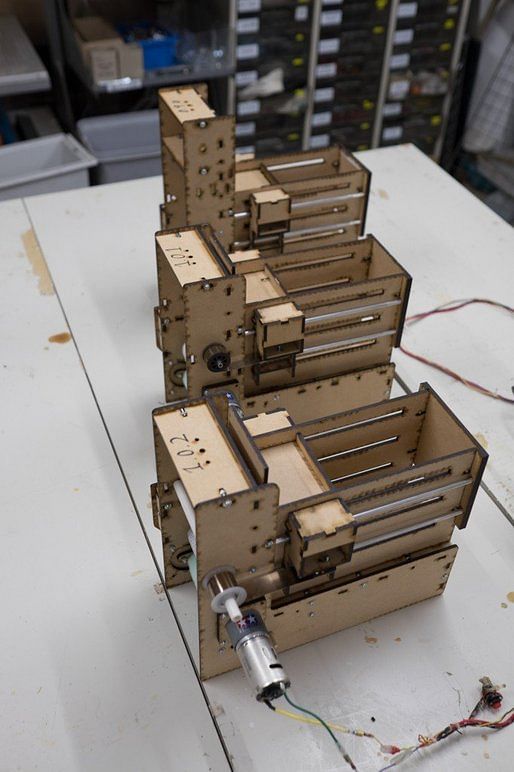

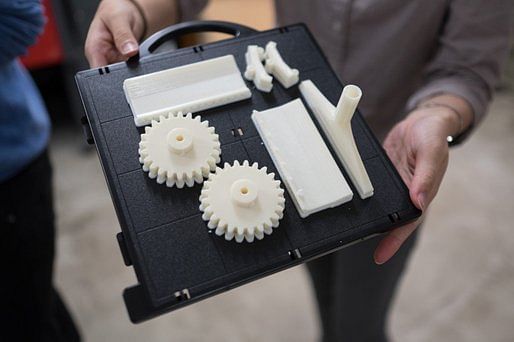

The "machine team" worked to finalize the development of our "smart tool" with help from Shimizu, one of Japan's largest general contractors. There was still a lot of work to get the various mechanisms required to work properly.

A second team, led by Igarashi Lab, part of the computer science department here at the University of Tokyo, continued to develop the 3D-scanning system.

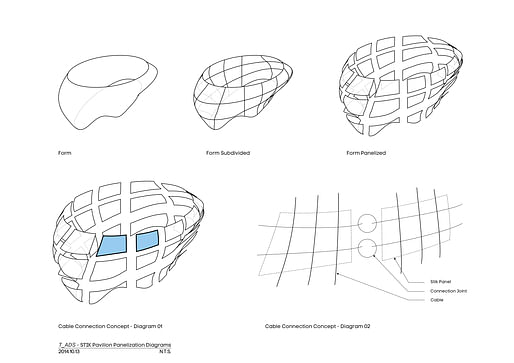

The third team focused on developing and documenting the final design and construction of the pavilion itself. During the break, it had been decided that, due to time constraints, as well as a desire to test the flexibility of the system, we should construct the final pavilion as a panelized system, rather than pouring the entire structure in-situ (as we had done with our circular mock-up). This created a whole host of unanswered questions, as we weren't sure that connecting the panels would be structurally and aesthetically possible.

The final team led our fabrication efforts (with help from everyone else). They produced a full-scale mock-up of a slice of the final pavilion to see how much cantilever we could achieve. They also led our tests to see if we could really panelize the system, and developed many details as a physical reality before they had been drawn. In other words, the construction documentation process was as much driven by the physical act of building as it was through drawing.

We were really surprised that this wall could cant out so far and still stay standing without support (however, there are a couple of concrete blocks in the foundation). Finding room for cautious optimism, we felt ready to start on the final construction.

A student blog dedicated to ongoing happenings in and outside the Advanced Design Studies Program at the University of Tokyo.

6 Comments

Are the chopsticks uniform material, i.e. basswood or bamboo, or mixed species?

Have you considered laminating them in specific orientation to construct modular building components?

What exactly does the 'smart tool' do?

Hi Miles,

The chopsticks are almost all Japanese cedar, At the end we had to use some pine as our supplier ran out of the cedar. The strength really comes from the shape of the stick (smaller, thinner sticks make it stronger) and the type of glue you use. That being said, I think there's lots of room to experiment with the aesthetics of using different types of wood, perhaps blending from one type of wood to another, or changing the size of the sticks in order to vary the amount of light filtration (as an example).

We've just stuck to this simple method of dropping the sticks on top of each other. That's a nice idea to think of how modular components could be fabricated in order to make the system more practical and able to scale-up. Right now, for water-proofing, we have just used a simple water-proofing spray and we've built another project that will stand outside a couple years, so we'll see how it performs outdoors over the semi-long run (I'm assuming that's why we would laminate them?)

The "smart tool" really needs its own post by someone who worked on it more closely than I did (forthcoming after the holiday break). The concept was (is) to develop a kind of hand-held 3D printer. Anyone could just pick this thing up, flip a switch and then the machine would guide the worker in where to aggregate the material.

The subject of this year's studio for new students will probably revolve around developing this idea further as there is still a ways to go and I think it can extend beyond this stick project. Basically, instead of trying to automate everything, is there a way to still let people do what they do best, but with more guidance from tools they are using.

thanks much for your questions.

Re: material supplier: are the chopsticks recycled?

Hi Miles,

They are by-products of the chopstick manufacturing process.

Similar to how they make studs for stick framing, in order to make commercial-grade chopsticks, the manufacturer planes the section of the tree and then only uses the rectangular, middle portion of the tree to produce the utensils. The sticks we used came from the curved pieces that are leftover and usually thrown away or used to make other lower-grade timber products (something like OSB or particle board).

We wanted to actually used "used" chopsticks but it's difficult to collect so many of them and then clean them and prepare them for use. At the beginning of the project, we considered putting some resources into making a machine that could rinse and make the wasted chopsticks into something usable, but we didn't get to it and it wasn't possible to buy them in any conventional way, as they're not generally separated in recycling processes here in Japan.

That being said, two of my classmates are continuing this research project as part of their thesis, and they plan to spend more time looking into how they could change current waste processes with regard to disposal of chopsticks.

The benefits of disposable consumer goods!

Thanks.

Japanese are really great when it comes to technology.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.