Jul '14 - Sep '14

This is the first post of, what I hope, will be a series of posts exploring the nature of architecture as it relates to social justice in current design practice. Thank you for taking the time to read this, and if this is of interest to you, you can respond to me here or on twitter -- Matt

Where I sit currently, I can almost make out the scene of what many consider one of the worst man-made disasters in human history; the breaching of the levee in the Lower 9th Ward. Much has been said about that event, but the fact remains: the industry I belong to contributed to the obstacles faced by the residents of the Lower 9th Ward, and not just when the levee broke, but before as well, and in many other communities around the world; Pruitt-Igoe, Cabrini Green, Torre David, redlining practices... the list of transgressions is long.

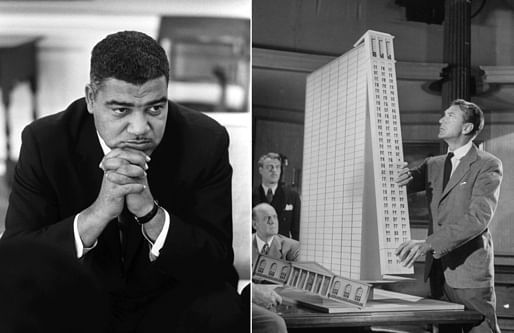

In Wisdom From the Field, the authors of the report, funded by the AIA Latrobe Prize, begin their executive summary with the following quote from Civil Rights leader Whitney Young before the National AIA Convention of 1968:

You are not a profession that has distinguished itself by your social and civic contributions to the cause of civil rights, and I am sure this does not come to you as any shock. You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete irrelevance.

What has since followed, and is addressed in Wisdom From the Field, is a call to action for those operating in the built environment. Many fantastic examples of social impact design have emerged. From Sambo to MASS, you don't need to look hard to find practitioners in the field who exude passion for not only the work they do, but also the communities they serve. Unfortunately, at the same time, they are the exception and not the rule.

It is likely true that for most designers, not all will have the same capacity, talent, or success to be the next Rem, Zaha, Frank, or Bjarke. However, with passion for the work you do, and ingenuity in how you design the systems that deliver great projects to people in need, you may be able to join the likes of Bryan Bell, Marc Norman, Emily Pilloton, Teddy Cruz, David Perkes, Jess Zimbabwe, John Peterson, Katie Crepeau, or one of the many others who are leading the charge for practitioners who aspire to serve their communities and not just their clients.

When architects begin to listen to the needs of not only their clients, but also to the primary needs of those their projects affect - and to do so in a manner that is not token participation but instead empowers and educates them to overcome social injustices they may have been dealt - then we may find that the most sustainable form of architecture is found when a design fosters community ownership amongst those it serves.

5 Comments

The vast majority of architects work in, and for, their communities. One does not have to practice "community design" to address the needs of a populace or urban area.

No, the big names frequently do not do this, but as a whole, mega-scale projects have difficulty satisfying those who advocate community design, no matter what strategies they employ.

I would be very careful of conceptualizing "community design" as something distinctive or unique within architecture. It is absolutely ubiquitous, but there is no way to tell this is the case from academia.

Don't architects serve clients? As far as what I have heard from professionals. Architects are meeting clients needs without regard to the community their projects are in. Its a matter of incentive. Architects are paid to do what the client wants the quickest and the cheapest they get return clients.

Very few clients are concerned about what effect their buildings have on their communities or the planet. Architects can step up and stand up for better design practices when their clients try to compromise things that should not. At the same time their will be architects out there that will for a buck.

I applaud the architects you mentioned that design shelter for people in need and that work. At the same time those people who need them are not paying for those buildings. The majority of buildings architects are designing are by clients who are paying their MONEY for what THEY want.

@ Archanonymous,

Thank you for the thoughtful response. By and large, I agree with the points that you make; many architects do work in their communities, architects don't have to work as 'community designers' to address the needs of a particular community, and that mega-scale projects can be more difficult to satisfy the principles of community design.

However, I would disagree with you on one point:

Community Design, or design that is primarily in pursuit of serving the public interest, is not ubiquitous within architecture as a whole. Architecture (in the context of business) concerns itself, primarily, with the operations required to bring in new projects, successfully complete them on time and under budget, and hopefully make a decent profit. This relationship between the owner/client and the architect is the standard historical framework for which much of what we call architecture operates within.

What is being called Public Interest Design - or Social Impact Design, depending on who you talk with - is gaining traction as an entirely different subset within the field, based on the reconceptualization of how the business of architecture operates. The architects I've listed are only a few of the many designers out there that have used their creativity to not only create new projects, but also create new models of practice. I think that warrants a distinction, and it is different enough from business as usual to not be considered ubiquitous.

Further, by highlighting them as leaders, my hope is that other individuals who are inspired to have greater social relevance permeate their work might be able to follow the links and begin to understand the methods that they utilized in in order to redefine their personal scope or practice.

A larger question your comment speaks to, and one I plan to share my thoughts on soon, is who constitutes the 'community', and how can architects that are not in pursuit of public interest projects better incorporate the principles of community design into their own process (and why they should).

Matt

@ Fergie,

You've hit the proverbial nail on the head. Clients drive design decisions, because it's their money. Architects who serve clients, as most all architects do, operate within an industry that has standardized our work as a commodity upon which those with financial means can construct space. And as you pointed out, clients are not always altruistic in their approach.

For the clients that are altruistic in their design decision making process, there is no limit to how positive a design project can be, for the architect, the client, and the community that stands to be affected. For those that are primarily concerned with time/budget/quality, as I wager nearly all are, architects consistently find themselves between a rock and a hard place. We may desire that the project is well received, aesthetically beautiful, and environmentally/cost-efficient, but we nonetheless exist to provide a service to our client first and foremost.

What I'm advocating for, and believe is not only possible, but potentially a preferred method to how a portion of architects operate today, is a framework of social sustainability that measures our community engagement for enhanced public impact much the same way that we measure our R-values for thermal comfort.

As an industry, we've managed to successfully develop methods for translating complex issues regarding sustainability to clients that otherwise might be unaware or undecided, and in many cases we've made excellent strides to design better buildings by simply linking our design decisions to the relative cost of energy (thereby saving the client money).

Is there a similar 'cost of energy' when architects/clients are not designing with the community in mind, thereby expending more energy/cost in the form of public relations, budget overruns, design revisions, city hall meetings, variance requests, and perceived transparency? I think so, and that's what I'm planning to address in subsequent posts.

Matt

Matt,

Yes, that is a very important distinction. I do feel like I know many architects, and even Architects, who consider community health in each and every design, but we tend to be much more apathetic about it at even a firm-wide level, (and certainly an industry-wide level) where the practice of Architecture really plays out.

Thanks for the well-considered blog, I will be sure to check out the next.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.