I have become particularly impressed by a group of architecture students at Woodbury University who run an organization called ASTERISK. Kayla Castro, Karin Najarian, Ezinneka Emeh, and Mohamad Annous are all third-year B.Arch students in the School of Architecture, and they have — among others during this time — begun to challenge the male-dominated eurocentric canon they have observed in architectural discourse. These four, I think, are prime examples of the kind of character that grows from a sincere desire and determination to bring about change and to challenge long-held conventions.

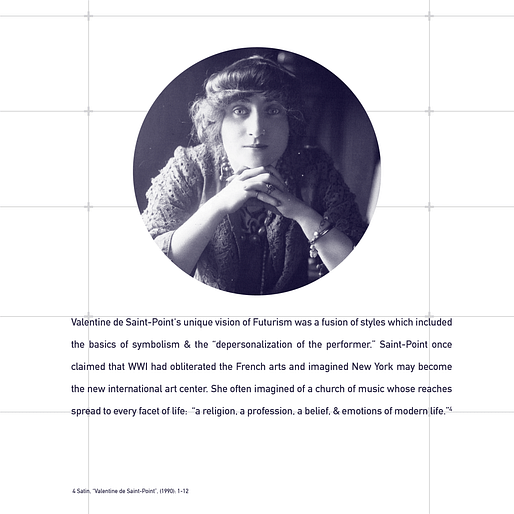

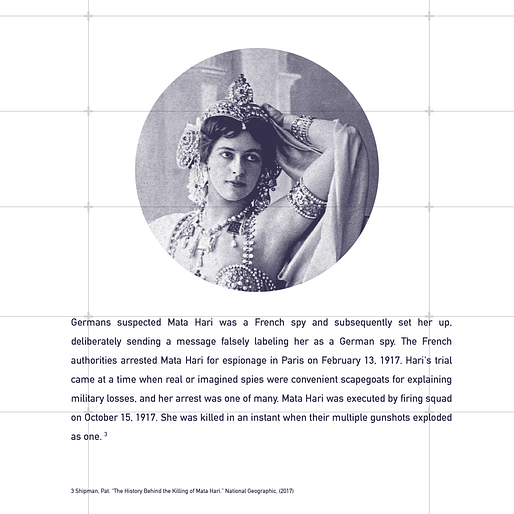

When the quartet began to realize that there was a bias embedded in how architecture history was presented to them, they began to question the overarching narrative of that “history.” While the school is actively working to reform its curriculum, students are given an open voice to engage, challenge, and interact with the various modalities of pedagogy within the institution. Today, ASTERISK leads assemblies where students, faculty, and staff gather to engage in discussions around the asterisks of the architectural story. The group has covered figures like Emily Warren Roebling, Rosa Mayreder, Mata Hari, Pedro E. Guerrero, and Norma Sklarek, among many others.

I connected with the group to learn more about their journey, how they manage to lead ASTERISK with busy architecture student schedules, and some of the lessons they’ve learned along the way.

Sean: Why did you start ASTERISK? What’s it all about?

ASTERISK: Recently, we all had a class about architectural-historical figures that we had heard about a thousand times before (read: Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, etc). Any professionals of color or non-male designers were briefly introduced before the discussion moved on to the talents and manifestos of the idealized white male architects. We were grateful to be introduced to the minority designers but were bothered by the fact that actually knowing the stories of these sidelined figures was of no consequence to our grade in the class.

Students need to show initiative in expanding the narrative to include figures that don’t fit into the Eurocentric paradigm.

The four of us met and we came to a conclusion: students need to show initiative in expanding the narrative to include figures that don’t fit into the Eurocentric paradigm. By doing so, we hoped our interests would attract others that share our curiosity. Our assembly creates a space that brings to reality the issues we come across. ASTERISK currently has three series that focus on a different array of figures throughout time.

UNSUNG is centered around historical figures.

INSIGHT is about learning from our faculty members about their experiences and areas of expertise.

HERE & NOW is based on contemporary figures that are currently practicing and that we can still learn from.

Do you think you are the first students to feel this way?

Absolutely not. As students, we knew the curriculum needed to change but we didn’t know how to go about it. We met with our Assistant Chair Aaron Gensler who avidly listened to our concerns. She told us about her experience at Cornell with discussion groups and lectures she organized for her class and gave us a lot of options for how to turn our passion into action. After that meeting we had a long discussion amongst ourselves, ranting about all the issues we would like to bring to light with this student group. We decided our goal is to bring these subjects into the national curriculum, and starting this discussion group would be the first step.

Why do you feel, with your busy schedules as architecture students, that it is worth it to take the extra time to lead this discussion?

Even with our busy schedules, we feel that if we don’t do it, we won’t learn about it, so we make it a priority. Representation in any field is crucial to success and we are able to see ourselves in these minority designers and practitioners. As we did our research, it became apparent that there are many other ideas in history that are hardly discussed. These ideas provide a wider array of precedents to study when designing which is crucial for problem-solving. Though these presentations take time and research to prepare, we are adding to our toolbox of concepts to choose from. We have noticed that we are becoming more conscious designers, so the sleepless nights will pay off in the long run.

What would you like to see change in architectural education? Do you see any changes happening?

Our experiences in architecture theory and history classes all align; we learn about the same few idealized people repeatedly. This type of worshipping results in these figures becoming untouchable; their successes will always overshadow their misconduct. For instance, among the four of us, we had been taught about Le Corbusier for at least the past three years, but somehow, this year was the first time we heard about his defacement of Eileen Gray’s E-1027 house.

Gray designed this house as a critique of Le Corbusier’s rigid five pillars of modernism, arguing that a home should not, in fact, be like a machine, but instead a natural and comfortable extension of the inhabitant. When Le Corbusier saw it, he felt it was blasphemous that his guidelines were not followed — or perhaps felt jealous that her rendition was more successful — prompting him to vandalize her property by drawing graphic murals on the walls that made fun of her bisexuality. Because it is now covered in famous Le Corbusier murals, the entire house sometimes gets attributed to him.

This story fell into a pattern that we had begun to notice: The pattern that Adolf Loos fell under when he designed essentially a fishbowl for the talented African American performer, Josephine Baker to live in. The pattern that the Bauhaus fell under when integral women like Lucia Maholy were rarely given credit for their work, instead attributing her husband Lazslo Maholy-Nagy or Walter Gropius. Once we started seeing the pattern, we couldn’t ignore it. We wondered: how many other instances are there where the minority figure has been rewritten as an asterisk in a white man’s story? And what role does academia play in silencing those asterisks?

We are currently working with the Woodbury School of Architecture administration to bring ASTERISK into the curriculum.

Ultimately, we want the NAAB curriculum to expand and include the full scope of architectural history. An accredited undergraduate architecture program is five years, which is plenty of time to learn about many different designers and practitioners. We are currently working with the Woodbury School of Architecture administration to bring ASTERISK into the curriculum. You may see it offered as an elective in an upcoming semester!

What does a typical assembly look like?

Once every other Thursday we explore patterns throughout history where certain narratives become reduced to a mere asterisk. We begin with the figure’s history, their contribution to the design world, and examples of their work. More often than not, the figures have ties to popular designers; those relationships are also explored side-by-side. After the introduction, we ask the room a question that ignites a larger discussion based on the figure’s narrative. A pivotal aspect of our discussions are the attendees; their shared experiences allow for the perception of the figures to become relatable. Anyone is invited and encouraged to participate in our discussions!

You’ve researched many important people. Could each of you share one of your favorite subjects and what you learned from them or what impacted you in their story?

Kayla: Marion Mahony Griffin was a direct victim of Frank Lloyd Wright's ego. She was hired by Frank Lloyd Wright and oftentimes designed and led an entire project. When Wright would drop a 5-minute sketch and run off to Europe with married women, his team was left to design the structure with very little direction from Wright himself. Authorship of some of these structures is still unclear. Mahony Griffin was also a talented renderer and used her talents to help clients visualize projects. Mahony’s style of rendering became known as Wright’s style as he took credit for many of the drawings.

As a woman of color in architecture, I have faced my share of doubters, discreditors, and sexualizers.

The reality of architecture history is appalling, but it is a truth we need to face. When uncovering figures like Mahony, I find myself emotional because I can relate to their narratives. As a woman of color in architecture, I have faced my share of doubters, discreditors, and sexualizers. For a short time, I worked with only men at a general contractor's firm where I was faced with a lot of “get used to it” comments. Once they learned of my skill set, I soon became their “architect.” I was told to produce renderings of the structures we were working on for the client to visualize the project. I was told I would receive payment for these drawings, but I was never compensated for my time nor given credit to these drawings. As designers, we’re faced with advocating for ourselves, our time, and our talents. As Mahony knew, this can become challenging when you're the only woman in a room full of doubtful men.

Karin: Emily Warren Roebling’s story resonated with me most. She was a self-taught engineer who took on the role of head engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge out of necessity. Her father-in-law was the original engineer who fell ill and died before construction began. The role got passed down to his son, Washington Roebling who also got sick with an incurable illness that rendered him bedridden for the rest of his life. Emily had to step up and relay messages from her husband to the workers on site for eleven years. She was never officially named the chief engineer, but she handled all of her husband’s duties with such mastery that the workers thought she might as well be.

Emily Roebling was skilled in science and algebra but did not have any official engineering training. For her to learn the applicable skills on the spot while also taking care of her sick husband is incredible. She was also a mother of a young child at the time so she had those responsibilities as well.

The people that we have discussed in ASTERISK so far have had so many hurdles to overcome in their personal life in addition to the discrimination they were facing in their professional lives. Many were mothers and some were single mothers, which is already an incredibly difficult job, and they still managed to make history to make it easier for future little girls to follow in their footsteps. A lot of the idealized figures we study in school don’t seem to exist outside of their work. It’s comforting to read about people like Emily Roebling who are so well-rounded and still successful.

Mohamad: Norma Slarek’s journey can resonate with many; her narrative as a working single mother transcends race and time. As a Black woman in the 50’s, her life was spiked with obstacles and hurdles, which she completely obliterated from her path. I remember seeing a photo of Norma in a common meeting environment, surrounded by white men who were paying their full attention to her. That image is evidence of the power Norma had over her life; the strength that representation possesses, is in no doubt, a nexus of inspiration for women, and more significantly for black women. More specifically, the image she provided for her children allowed for an instantly positive representation of what Black excellence could look like, first-hand.

Norma reminds me of my mother, who is also a single mother and a boss. I remember witnessing my mother, a civil engineer, lead an entire group of men on her team. Photos of my mother would be plastered in every newspaper, at least a couple of times a year, and those photos are almost identical to Norma’s. Some photographs consisted of my mother, the head engineer, in the middle of the photo, with her all-male team to the right and left of her. Aside from her career-driven successes, she is a balanced, self-actualized person, who also did not allow society to dictate any aspect of her goals and dreams. Those people become synonymous with prosperity and respect.

Ezinneka: Sophia Hayden Bennett was an American architect. She was the first woman to receive a degree in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). On February 2nd, 1891, the Construction Department of the World’s Columbian Exposition announced a competition for the design of the Woman’s Building, one of the exhibition halls to be constructed for the 1893 international exposition in Chicago. Hayden won the competition with a design of a three-story building. She designed the building when she was 21. All aspects of the building were planned by women.

The Woman’s Building was one of the first fair buildings to enter into construction, during the summer of 1891, and the fact that it was finished and ready for the opening of the Exposition and within budget suggests that Hayden had mastered the managerial aspects of the profession as well as the artistic ones. Because the Woman’s Building was demolished after the Exposition closed in 1893, no structural record of her career exists.

Misogyny played a role in halting Sophia’s architectural path. From not being able to find a job as a female architect to only having one building design ever actually constructed (and later demolished). This, however, did not stop her from designing. She was a talented woman who inspired more women to pursue a career in architecture. She was passionate and did not let remarks about women being unable to perform to a certain standard in architecture stop her. This inspires me to keep going.

—————

You can follow ASTERISK on Instagram @asterisk.wsoa.

My reflections, thoughts, ideas, and observations during my time working and teaching at Woodbury School of Architecture in Burbank, CA.

2 Comments

Thank you for this, Sean.

Thank you Sean and Archinect for opening up this forum.

What the Woodbury students are presenting and discussing is a very well known architectural history discourse that falls out of the canon.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there are many paths in academic curricula that have fostered other histories.

Personally, I am in favor that they speak up and loud.

Here an example of a today event at Columbia University. It was presented by the students in the middle of the strike.

Jacqueline Taylor, Independent Scholar - "Complicating the Canon: Modern Architecture and the Black Middle Class" with response by Mario Gooden.

Let's continue this conversation. We can learn more about the field.

Maristella Casciato, Senior Curator, Head Architectural Collections | Getty Research Institute | (310) 440 7319 | getty.edu

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.