For many of us architecture is a calling, for others it’s a job and for some it’s a lifestyle. Regardless of which description(s) best fits your personal perspective, as designers there are a few important questions that will unify our cause and help to shape our professional lives. These questions include: What type of architect do I want to be? What type of education or institution will help me to become that architect? How do I get the attention of employers in such a competitive field? And How do I realize my full potential in the professional world?

Introduction to the Series

The following essay is the first in a series that will attempt to guide us in answering those questions. This series is written for designers who have firmly decided that architecture is a career path they wish to pursue. I do not intend to go through the arguments about whether anyone should become an architect and how to tell if you would be a good one. In addition, I will not digress into the pessimism about low salaries, long hours and poor working conditions that run throughout the profession. This series is meant to raise our spirits and ambitions within a tough economic climate, provide some helpful advice about portfolio preparation and the search for employment and contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the forces that shape our professional lives.

With the current economic downturn forcing many talented designers back into the academic world or into the realm of unemployment, we must remain focused on conveying our talents and experiences in the most effective manner to remain competitive. Part One of this series will include advice on preparing an academic portfolio and applying to graduate school while parts two and three will focus on the search for professional employment and the interview process. I have included examples of my design work and detailed some of my own personal experiences while engaged in these processes. The articles in this series will consider questions from hundreds of past discussion threads and provide one central resource for answers.

![]() Download as PDF

Download as PDF

(Filesize: 76 MB)↑ Click above image to preview entire portfolio in condensed format for a quicker overview

Dreams Conceived in Twilight:

Undergraduate Design Portfolio by Jason Ivaliotis

Graduate School Application Portfolio

Size: 8.5”x11”

Spiral Bound

![]() Download as PDF

Download as PDF

(Filesize: 97 MB)↑ Click above image to preview entire portfolio in condensed format for a quicker overview

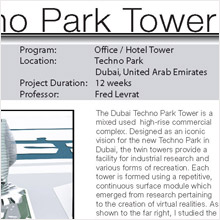

Graduate Design Portfolio by Jason Ivaliotis

Features Work Completed during Graduate Studio Sequence

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation

Size: 8.5”x11”

Spiral Bound

![]() Download as PDF

Download as PDF

(Filesize: 62 MB)↑ Click above image to preview entire portfolio in condensed format for a quicker overview

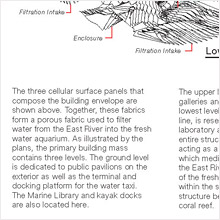

GKIP Studio – Technical Portfolio

Columbia University

Advanced Building Systems II

Project: Industrial Loft Design: Architecture + Engineering

Collaborative Work Completed by Jason Ivaliotis, Nicolas Kothari, Jamison Guest and Donna Pallotta

Size: 8.5”x11”

Spiral Bound

Academic Portfolio Preparation and Application to Graduate School

For a majority of people, the future will be determined by a handful of critical decisions that directly impact the course of our lives and help to shape the type of people we will become. While many of these decisions are highly personal and vary from individual to individual, there is one that remains universal: the choice of education. Placing this into context for designers who wish to pursue higher education, choosing the right graduate program may be the most important decision of your career. Graduate education will set the tone for professional aspirations, help to shape the personal design process, and greatly influence how you view the built environment and contemplate your place in its conception. The right school will open many doors and generate limitless professional opportunities; you must choose what type of doors they are and what you seek on the other side. The following article will outline some of the things I have learned while assembling my personal academic portfolio and graduate school application package and offer some advice to young designers who are about to engage in this highly competitive process.

Scroll to read all the sections, or select one of the following links for a direct jump:

I. Preparing for the Application Process: Research and Observation

While most architecture students consider the long days and nights in studio as a difficult right of passage, this experience is also the foundation of design culture and education. The studio is a laboratory of ideas where students are able to learn more from peers than professors. It is important to remain observant, self critical, and immerse yourself in as many different design courses as possible to gain proficiency in multiple techniques and processes. This will make it easier to determine what interests you the most about architecture and how to best pursue that interest after graduation. It is also important to pay careful attention to your classmates’ design process and presentation styles. Frequently engage your peers on subjects such as graphic representation and portfolio preparation. From the larger collective, you can often determine what techniques of representation are most effective in assembling the visual narrative of any given project. Although these peers may eventually be your competition, while engaged in the rigorous and energetic environment of academia, they are also your greatest resource.

II. Take Some Time Off from School

The application process is a very intense and time consuming challenge. There are many advantages to taking some time off from school to clear your head and refocus your energy after finishing undergraduate education. Working in a professional design office or related field of interest will allow you to obtain some valuable work experience so you are not later coming out of graduate school cold, with a significant amount of student loan debt, no professional training and entering into an entry level position which does not offer a salary that satisfies your financial obligations. A graduate of a Master of Architecture program who already has one to three years of professional experience is more competitive in the marketplace than someone who has six to seven years of design education but no work experience. The intense competition in the professional environment demands that every young designer put the best foot forward and take some time to reevaluate life after school, determine where you want to fit into the profession (if at all), and build up a network of valuable contacts which may eventually help you gain admission to the graduate program of your choice.

Engaging in the application process while still completing your undergraduate education may put you at a distinct disadvantage. The academic portfolio should contain only your best design work presented as an impressive visual narrative. If you apply to graduate school while still in the senior year of undergraduate education, you may not have time to enhance any previous studio projects while still completing academic coursework. Furthermore, any studio projects from the senior year of undergraduate design school are unlikely to be included in your application portfolio because of early submission deadlines. These final projects may be the most important and competitive additions to your portfolio as they represent the capstone of the undergraduate education. Therefore, rushing to apply too early may put you at a disadvantage to others who have a more comprehensive and carefully assembled portfolio.

While contemplating which graduate programs best fit your interests, it is also important spend significant time researching academic scholarships and grants. The full cost of graduate education can range from $60,000 to over $200,000 and will remain a financial burden for many years after graduation without relief from grants, scholarships or fellowships.

III. Developing a Competitive Edge before the Application Process

The interim between undergraduate and graduate education provides an opportunity to obtain proficiency in several different areas which will increase your competitive edge in the job market and enhance your graduate school application. Some of these educational pursuits include taking courses in digital/BIM software, becoming LEED certified, and completing hours for the Intern Development Program in pursuit of professional licensure. For students who have no design background or those wishing to enhance their design skills, take a summer introduction to architecture course at a school where you will eventually apply. In this environment you can meet the students currently enrolled in the program, as they typically serve as instructors or assistant professors for design courses in the introductory programs. You will also have access to some of the full time faculty at each school and these individual professors can become valuable sources of information during the application process. They are able to get to know you as a designer on a more personal level, give advice on portfolio production, write letters of recommendation and an provide an inside perspective of graduate design education at their respective institution. These educational activities will enhance your design education, provide an outlet for developing skills which are later used in the professional and academic environment and provide a structure for the production of design projects to be included in the application portfolio.

IV. The School Selection Process

The selection of the appropriate school is a very personal process that requires a significant amount of research and individual reflection. You may want to start by asking yourself some general questions that will help focus the search towards a school that is in line with your professional aspirations. These questions may include: Is education a simple formality on the road to licensure, or will a certain type of education facilitate my contribution to a larger theoretical discourse which will directly influence the formation of my own professional body of work? Do I view architecture/design as a 9-5 job, bound within the constraints of the office, or is it a state of mind that permeates into the various areas of my life, unable to be shut off or tuned out?

The current economic climate has increased the number of applicants, creating fierce competition and driving down admission yield. During the selection process, compose a list of 10-15 schools of interest and do some research on each program. Narrow your selection to between 6-8 schools with at least 2 ‘reach’ schools which may be more competitive and 2 ‘safety’ schools where you are confident about admission. Narrowing the focus allows more time to personalize the application towards each individual program. Remain passionate about attending each school on the list, as first choice admission is never a guarantee. The current economic climate has increased the number of applicants, creating fierce competition and driving down admission yield. If you are not admitted to your first choice, do not take it personally as there are many qualified candidates and not enough seats in studio.

There are various comparative resources on design education that can help you narrow the search. These include the ACSA’s Guide to Architecture Schools which contains basic information about all graduate design programs in the United States and Canada. In addition, the Design Intelligence annual ranking report will list the top rated graduate design programs from the perspective of professional design firms. The DI rankings are valuable in accessing the reputation of each school in the professional marketplace and the employability of their students after graduation.

While narrowing your search for the most appropriate design program and beginning the application process it is important to consider the nature of each academic program. Some considerations include the following:

A. Context: Decide whether you want to attend a school with a strong regional influence, a program that is recognized on a national level or an institution with a powerful international reputation. What type of environment will allow you to focus on your interests: urban, suburban, or rural.

B. Financial Burden: Is the debt is worth the return? Each student’s financial situation is different and spending $150,000 may have a serious down side for someone with a family or heavy financial obligations. A regional school may provide a good education that is much less expensive than an Ivy League program. However, if you are someone who can manage the financial burden, the higher price tag may be worth the return for the education you will receive and the professionals you will be able to access while enrolled in the program.

C. Life After Graduate School: Project where you may want to live after graduate school. If you wish to travel extensively and work abroad, look for a school with a good international reputation that offers study abroad programs along with professors who have strong international connections. Schools with strong coop programs also offer opportunities to travel and obtain valuable experience in a variety of professional environments.

Who are the professors and what do they pursue in the professional world outside of the school?

D. Know Your Audience: Perform extensive research on each school where you intend to apply. Much of the information for these programs can be found on the school’s website, student blogs which will provide insight into the program from the student perspective , the websites of alumni and professors in private practice, and NAAB related websites that provide an in depth review of each program based on a set of established criteria. Focus your analysis on the faculty, resources available and the facilities. Who are the professors and what do they pursue in the professional world outside of the school? Does the design program rely on theoreticians, practitioners or both? What aspects of each program has NAAB indentified as the strengths and weaknesses? Is the design curriculum art based, technically based or evenly balanced? Is the curriculum skewed towards studio or are there other opportunities to pursue secondary interests? Does the school have a regional presence or impact on its immediate surroundings, ie. community outreach/research programs or design build studios? What is the site context for studio projects…are they primarily urban, suburban, rural, international, focused towards adaptive reuse or environmentally responsive sites, or pursuing a new frontier? What types of facilities are available and do they correspond with your interests…digital fabrication, design and computation, algorithmic design, robotics, responsive kinetic systems, spatial information data mapping, theoretical design research, technical detailing, ect? These types of questions will determine if you are the right fit for the school and how to enhance the projects within your own portfolio and focus your essay to exhibit how you may fit into the pedagogy of each individual program.

E. Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Many schools offer dual degree programs in Architecture, Urban Design, Urban Planning, Industrial Design, Landscape Architecture and Historic Preservation. Within these programs, an extra year of education can yield a second degree and may increase your competitive edge in the professional market place. Whether or not you intend to obtain a second degree, attending a school which integrates multiple disciplines will enable you to take courses in various related subjects and interact with students who operate from a different design perspective.

F. Where are the Alumni? One way to determine how well any graduate program meets your academic and professional goals is to find out about life after graduation. Where do the alumni from this program go after getting their degree? Do they pursue teaching or professional practice? Are many alumni attracted to the culture of boutique firms or are they heavily recruited by large corporate design firms? Are they sole proprietors of their own practice or partners in larger collaborative offices? Many graduate programs like those at Columbia, University of Pennsylvania, Yale, the AA and others have an extremely contagious design culture and this tends to permeate into the practices of successful alumni. Personally contacting some alumni or simply doing a Google search may reveal a lot about the design culture or aesthetic of the program, the success of their students in the professional arena and how the design culture may serve your personal goals.

Some schools, such as MIT, will allow you to view the application portfolios of admitted students...

G. Visit Early and Often: It’s never too early to visit schools that interest you and start a dialogue with admissions officers and current students. I began visiting graduate programs and contacting students from each program the summer after my sophomore year of undergrad. Some schools, such as MIT, will allow you to view the application portfolios of admitted students where you may be able to identify the type of projects and visual presentation techniques that impress their admissions committee. A personal visit provides invaluable information that can not be obtained online from a distance. You can take building and campus tours, observe design studios and possibly talk to current students and faculty about the studio culture.

H. Speak the Language: Take some time to study contemporary architecture and design. Many undergraduate design programs may be so busy with survey courses requiring you to name every building in ancient Greece that they may not provide the academic framework to study contemporary architecture. Graduate design students speak an entirely different language and typically have a working knowledge of what the new, cutting edge design firms are accomplishing, who is winning which awards, what are the new tools and techniques, and which professional firms are pushing the design envelope. Studying these examples will prepare you to have intelligent conversations with your peers and professors about where the profession is currently, where it’s going, where you fit into the bigger picture, and how you can personally calibrate your design education.

V. Portfolio Design: Assembling a Visual Narrative

Carefully composed as a personal monograph, the design portfolio is an expression of your creative energy, professional talent and academic ambition. It is undoubtedly the most important part of the application package. The portfolio should be presented as a visual narrative, illustrating the thought process behind each one of your best projects from conception to construction.

A. Preparation: ... it is highly advisable to take some time during the summer recess in undergrad and before applying to graduate school to rework your studio projects and enhance the visual narrative of each project... The assembly of a comprehensive and visually compelling portfolio requires a significant amount of time and dedication. Academic studios are usually truncated, bound by the constraints of a single semester and may not allow enough time to thoroughly document the design process and the final product with the most pristine imagery. In addition, the learning curve of an architecture student is both long and steep. Projects completed in the early years of undergraduate education may suffer from a lack of development or a sophomoric presentation style. Therefore, it is highly advisable to take some time during the summer recess in undergrad and before applying to graduate school to rework your studio projects and enhance the visual narrative of each project with all the supporting drawings and images that were not completed during the course of the semester. Many of the images in my undergraduate portfolio were completed during the summers between studios and in the 7 months before applying to graduate school. Taking the extra time to enhance each project was helpful because I was able to visually explain each piece on my own terms without the time constraints of a semester studio or the professor’s agenda getting in the way. I was also able to apply presentation techniques learned in later years to earlier studio projects, thereby allowing the entire portfolio to be evenly balanced where each project had a similar level of design development and visual documentation.

B. Graphic Design Precedents: The application portfolio is the most effective tool for graphically marketing your talent in one concise presentation. Examine how professional firms market their work and compete for projects, as these are the best precedents for portfolio preparation. Look at websites and publications of up and coming design firms or designers who frequently compete for awards and competitions. Competition and design award submissions draw many parallels with portfolio preparation. They are focused towards a specific audience and are clear and concise, typically requiring the contestant to make a powerful design statement within a small number of slides. Pay close attention to the types of images used to explain the design process (diagrams, renderings, sketches, technical drawings, etc.), the techniques used to enhance these images and the organization of the overall package.

There are many professional publications that serve different types of professional firms and exemplify various graphic languages. In addition, there are many professional publications that serve different types of professional firms and exemplify various graphic languages. Design firms look to these journals as precedents for portfolio preparation. The portfolios of many boutique and hospitality firms are heavily influenced by Metropolis , Wallpaper , Frame , Mark , Surface and Hospitality Design Magazine . The Korean Magazine, BoB serves as a precedent for different styles of photography and photo treatment. Architects and Engineers often refer to Detail Magazine , Architecture Magazine , MONDO , Abitare , and El Croquis for their clean page spreads, use of white space, font size, project layout and presentation of technical drawings. Smaller studios tend to look at the aesthetic of ACTAR publications such as Verb or Boogazine . Many of these publishers have attracted their own niche market and retain specific audience appeal. Publishers like teNues , Princeton Architectural Press , Actar , 010 Publishers , and Rockport exhibit very elegant and clean corporate design layouts with a modest amount of text on each page, never crowding images and maintaining nice font spacing. These publications can be a great source of inspiration for graphic organization and a clean, concise presentation style.

C. Organization: The ability to effectively communicate the ideas and merits of each project with an organized sequence of supporting images and a clean presentation style is a testament to your character as a designer. An academic institution will want to know how methodical your design process is, and how well you can explain yourself through this visual narrative. Each project should be documented through conceptual sketches/drawings, process models and eventually technical drawings, perspectives and physical models of the final design. A sequence that organizes and details each project from conception to construction is often the most effective way to communicate how well you understand your own work and if you are able to convey the main ideas to a design jury or prospective client.

When considering length, number of projects and overall design, try to find a ‘middle of the road’ layout from the requirements listed by each school (somewhere between the most restrictive or reductive parameters and the most liberal). This method will allow you to flip back and forth between the submission parameters for the most restrictive and least restrictive schools, adding and omitting things as needed. Following the most restrictive parameters for all application portfolios can be very dangerous as this may result in the omission of work that would give you a competitive advantage at a school with more liberal submission requirements.

1. Choreography

A successful portfolio makes a powerful statement using only the most essential imagery. Carefully choreograph the narrative of each project, selecting only those images, diagrams or models that clearly express an idea. You do not have to include every perspective, design sketch or rendering completed for each project. Portfolios that are too long may cause the reader to lose patience and either glaze over essential portions or refuse to finish reading.

2. The Project Order

While all the selected projects should represent your very best work, there will ultimately be some projects that stand out as the cornerstones of your portfolio. Chronology is not as important as content and choreography. You must keep the story moving and the audience interested. Begin with a powerful statement that captures the reader’s interest by placing one of your three best projects first. Place another powerful project in the center and close with your most advanced or significant project. The final project should leave the reader with a lasting impression as this will be your last chance to impress him or her before your application package is rated for admission. As an example, I have provided my undergraduate portfolio “Dreams Conceived in Twilight”. Within this portfolio, I have opened with a project from sophomore year which establishes proficiency in graphic representation (specifically hand drafting, sketching and rendering). The central project, “the Tower of Babel” is a collaborative, high rise design studio which exhibits the conception of a new type of highly complex skyscraper and the fabrication of a 15’ scale model to support the final design. The final building is a competition entry completed during my senior capstone studio. This was a large group project, and the visual narrative was represented in a variety of different media. To leave a lasting impression on the reader, I concluded with a large, hand drawn perspective of the building in context or what students like to refer to as a “money shot”.

3. Length and Content

Overall length of an undergraduate portfolio is often the subject of debate and requirements vary from one school to another. Many schools will impose or recommend a page limit, but you must ultimately rely on your own judgment. Each project many require 2 to 4 page spreads to explain in full, which is perfectly reasonable provided that all imagery and information enhances the narrative and remains relevant and impressive, not repetitive or superfluous. However, an academic portfolio should appear concise and be no longer than 45 to 60 pages in total length. If the portfolio is any longer, you may be including too many images and not keeping the story flowing along rapidly. The key to leaving a lasting impression is to get in and get out as efficiently as possible and tell a powerful story with only the most impressive projects.

There is always that one moment in every portfolio which screams, “this project got them in” and that moment does not always occur in the architecture section. Introduce yourself as a designer with diverse interests and proficiency in multiple areas. Students without a design background should include any artistic projects, graphic design, photography, visual art, studio projects from introductory courses taken at architecture schools like those offered at Harvard and Columbia, and any other creative work that supports your interest in design and exhibits why you will excel in a graduate program. For students who have a background in architecture, a portfolio will typically contain 4 to 8 well documented projects, depending on the number of design studios taken at the undergraduate level. In addition, include projects in other courses of study like photography, sculpture, or visual art to show that you have a wide range of experience that will add to the diversity of the incoming class. There is always that one moment in every portfolio which screams, “this project got them in” and that moment does not always occur in the architecture section.

4. Professional Design Work

Most graduate programs will encourage potential students to include any professional work completed as an intern that is particularly impressive and directly exhibits the professional character of the applicant. However, these projects should only be included if the applicant had a significant role in shaping either the design or production process. The applicant’s role should be clearly defined and all featured images and design drawings should be properly credited to their respective author. Do not include a set of construction documents as these are not legible at small scale, not graphically unified with the other sections of your portfolio and reveal very little about your role in the project. Instead, feature enlarged details or technical drawings, sketches, or renderings of which you designed, completed or were directly involved in production. I have included this type of presentation within my undergraduate portfolio in section 7. This section features one of my first professional projects where I had a direct role in design and production of all images. Professional projects should not account for more than 25 percent of the portfolio as the admissions committee is trying to obtain a sense your design abilities, not those of your supervisor or team leader.

5. Resume

For applicants who have professional work experience, design awards or unique honors, including a resume in the portfolio will provide further insight into your character as a both a student and professional. However, once graduate school is complete, remove this resume from the portfolio as it will be outdated and conflict with your current resume which will always be in flux.

D. Graphic Presentation and Sequencing: A powerful graphic design strategy is one that clearly illustrates your personal design process, seamlessly transitions between projects, and visually ties the portfolio together into a cohesive presentation with a single graphic language. For guidance and inspiration, you may want to refer to page spreads in design magazines, observe how each project is presented and visualize how your work may fit into this format. A clean and simple layout can be the most effective. Limit the amount of images on each page, avoid layering too many images over top of one another as this leads to confusion. A visually busy layout that includes too many images or ideas on one page spread will make the viewer’s eyes wonder and he/she may lose patience trying to interpret too much information all at once. Sequence the projects carefully and lead them through the story gradually.

1. The Cover

For my graduate design portfolio, I chose a rendering from one of my lighting design projects to set the mood. The portfolio cover is your opening statement to the reader and will set the stage for the story inside. A vibrant and enticing cover design will enable your visual narrative to stand out amongst others when all portfolios are arranged on a table and compared. You can enhance the cover design with an impressive image or rendering from a project, a well crafted line drawing that you have completed or a strategic use of color. Whatever the cover statement, it should be simple and effective. For my undergraduate portfolio, Dreams Conceived in Twilight , I chose a landscape that supported the title. For my graduate design portfolio, I chose a rendering from one of my lighting design projects to set the mood. Other successful cover designs sometimes include a layered approach, featuring an image or line drawing overlaid with a piece of mylar to create some visual obscurity. The portfolio cover should include your name, degree(s) earned and the portfolio title.

2. Nomenclature

Include a table of contents at the beginning which lists each project and establishes some type of organizational system. A portfolio with strong graphic organization and a discernable language of transition will keep the reader engaged and prevent confusion. Include a table of contents at the beginning which lists each project and establishes some type of organizational system, referencing projects within the portfolio. The portfolio should have a graphic language that signals a transition from one project to another and unifies the entire compilation. You may choose to further divide the projects into sections such as architecture, photography, visual art, sculpture or professional design work. These sections should be established within the table of contents and graphically referenced on the pages of individual projects. For example, within each portfolio I used a numbering system for each project that appears in the upper right and left hand corner of each page spread for undergraduate portfolio, and lower right and left hand corner of each page spread for graduate portfolio. My undergraduate portfolio is also divided into the following sections: Architecture, Urban Intervention and Sculpture. The section title is clearly displayed in the top corners of each page spread for quick reference. In addition, both portfolios contain graphic title keys in the margins of each page spread which list the design studio level where each project was completed. This nomenclature is introduced in the table of contents and runs throughout each book, graphically unifying the entire volume, providing quick references and signaling a transition between projects.

3. Format and Sequencing

Each project should include a title page spread that indicates the name of the project, year completed, studio or course level/number, professor’s name, project duration, site location and names of all group members if completed as part of a collaborative studio. All projects should be organized with a similar style of presentation. Establish an underlying grid which will structure the layout of images and text on each page spread and carry throughout the portfolio to unify it as one visual presentation. Each project should include a title page spread that indicates the name of the project, year completed, studio or course level/number, professor’s name, project duration, site location and names of all group members if completed as part of a collaborative studio. You should design a graphic header to unify this information into one format that repeats itself on every title page and signals a recognizable transition between projects. Within each project, it is important to illustrate the design process in a coherent fashion showing the methodical approach to concept and how that was carried through to design studies, sketch models, final technical drawings and finished models. Diagrams are helpful to explain the thought process but should not take the place of tangible results. Two to four page spreads per project will usually allow enough space to feature larger images and explain the design process from conception to construction. Furthermore, a comprehensive presentation will show how each project responds to its design parameters and may include various media types such as sketches, computer generated drawings, renderings and physical models. Exhibiting a multitude of presentation materials, both virtual and physical, will indicate a diverse design background and a versatile skill set. Images and drawings should include a caption or system of footnotes to explain their purpose and place in the design process.

Editing the content of each project is extremely important. Not every single sketch or drawing generated during the design process will be important. Each selected image should say something new about the project and elaborate on the visual narrative. You are telling a story about your design personality and it should be constructed like any other good story, with an introduction, a climax and a powerful ending.

4. Include a Written Narrative

A written narrative for each project, integrated into the presentation, will explain and support the imagery. Do not be afraid of including text within the portfolio to document your thought process. A written narrative for each project, integrated into the presentation, will explain and support the imagery. Images can be glazed over by the audience and misunderstood without clear explanation. The written narrative should help tie everything together and serve as your proxy in the conversation between the portfolio and its intended audience. This is a good method to communicate your role in collaborative projects and cite drawings or images that were completed by other group members. In addition, the inclusion of this text will be of great assistance years later when you are trying to explain the nuances of the project to a prospective employer in a personal interview.

5. Font Selection

Sanserif fonts, such as Helvetica, Arial, and Swiss, are commonly used in design presentations for their versatility and professional appearance. The use of clean, and simple fonts will enhance the visual presentation of your work. Sanserif fonts, such as Helvetica, Arial, and Swiss, are commonly used in design presentations for their versatility and professional appearance. In addition, each of these font types will typically come with an extensive family of sub-fonts to use for bolding, italicizing, and adjusting kerning, stroke and size of letters. The use of one family of fonts will help to unify the overall presentation. Establish three to four different font sizes and stick to them. These sizes may include one for captions and image credits, one for narrative text, one for project titles and one for portfolio section titles or symbols. Lettering should not be too large as to take over the page or too small as to be illegible when printed. Running frequent prints is the best method to test the text at full scale and determine the appropriate font size and how well it enhances the graphic presentation.

E. Group Projects: Collaborative projects and competitions can be a very strong addition to your portfolio. Complex architectural projects are typically the result of intense collaboration between disciplines. If you can show the admissions committee that you have already reached a higher level of professional maturity and are able to collaborate on more complex design projects, it will greatly enhance their impression of you as a designer.

Many projects in graduate school are done in groups. These include projects completed in building technologies courses, visual studies courses, and collaborative studios where the scope of work is too ambitious for one designer. Jumping into the collaborative process early in your academic career will reveal much about your strengths, willingness to listen and mentor others, ability to compromise and work through complex problems, ability to satisfy project requirements, and your capacity to assume and delegate responsibility. These qualities will come through in the presentation of a successful collaborative project and are not lost on academics and potential employers who are looking for team players.

When featuring collaborative projects in the application portfolio, you must explain your precise role in the project and visually detail your contribution. All group members must be listed and properly credited for borrowed images that you did not personally create.

F. Peer Review: Discuss the design of your portfolio with your peers. Be sure to critique each other’s work and the graphic presentation of each project. In addition, present your portfolio to someone who is not an architect or designer to determine if a person outside the design vacuum is able to understand the process of each project and the merits of your work. This process will test whether the visual narrative is successfully exhibiting your strengths and abilities.

G. Publishing the Portfolio: Although the author controls the graphic presentation of each project, the overall appearance of the portfolio will rest in the hands of the publisher. Print quality, page size and binding type are all contingent upon the publisher. Finding the right publisher and choosing the correct media is a process that should commence while the portfolio is still in the early phases of design. There are two types of publishers for design portfolios: web publishers and printing/reprographics shops. For best results, you may want to find a professional printing house used by architectural and design firms for the production of marketing material and client presentations. Web-publishers, such as lulu.com are also fast, efficient and low cost publishing resources that offer many options for customization.

It is important to choose a publisher early as they will dictate the printable page spread format, which will ultimately determine the physical size of your portfolio. Web publishers, such as lulu.com, have their own page formats that govern how the final result will be presented. 8.5x11 is often the maximum portfolio dimension that any school will accept. This size lends itself to the display of large images, particularly in double page spreads. Smaller formats, such as 7x9, can be used for both academic portfolios and sample portfolio booklets that are sent out with resumes during the professional job search. Any format that is smaller than 7”x9” may compromise the graphic presentation, legibility and overall impact of your work by minimizing images and reducing font sizes.

The careful selection of a binding and media type will provide an effective armature for the presentation of printed material. The inside pages should be printed on a white, high quality, medium weight cardstock. This type of paper will give the pages some weight and durability. High gloss media types are not recommended as their shiny, slick finish can distract the eye from the printed material. Select a clean binding type such as a wire spiral, saddle stitch, or perfect bind. The type of binding is often contingent upon the page size and orientation. It is wise to check with your publisher and go through the available options before deciding on the format and overall size of the portfolio. You should order at least two test prints of the portfolio to ensure the print quality matches the images on the screen: one test print midway through the production process to ensure all images and text will print as anticipated with the desired color saturation, and one test print after the entire portfolio is completed so you can do final image calibration. Plan to finish your portfolio no less than 3 to 4 weeks prior to its due date so there is time for test printing and final touches.

VI. Recommendation Letters

The function of a recommendation letter is to give the admissions committee a sense of the applicant’s personal character, design ability, dedication to academic pursuits, and an overview of both strengths and weakness. Finding the perfect reference to write these letters is just as important as the content of the letter itself. Choose professors or professionals that you know personally and can address your talents, abilities, strengths and weakness based on personal interaction and mentorship. An impersonal, vague recommendation letter from someone who has limited knowledge of the applicant will not be received well by the committee members. They may think you are either hiding something or have trouble forming meaningful professional relationships that would give someone insight into your character. Each school wants to know why you are a good fit for their respective program. This includes everything from details about the talents you will bring to the incoming class, any weakness you possess and how the program will best enhance your professional character and compliment your abilities.

Each school wants to know why you are a good fit for their respective program. When choosing the best individuals to introduce you to each school, it is important to consider the professional or academic stature of each recommender. These references should be the people with whom you have formed professional or academic bonds and their credentials should be as impressive and credible as possible. For example, when I was applying to graduate school, my personal recommendations came from what I refer to as the “Power 3”. They included the chair of the Department of Architecture, the Chief Departmental Advisor, and the Director of Graduate Studies. All of these faculty members served as my professors and mentors during my time as an undergraduate at Miami University. I also served them as a teaching assistant for various courses and worked with them on special projects. Whether you are still in your freshman year as a design student or a seasoned professional, it’s never too early to start forming a preliminary list of your own “power three.” This will encourage you to proactively seek mentorship from your professors or supervisors and work more closely with them so they may have more insight into your character, talents and abilities. In addition, these mentors may keep in contact with an extensive list of alumni, many of whom attended the graduate programs to which you are applying. They will be able to reference these alumni in your recommendation letter, comparing your abilities to those of others who went through the same program, thereby providing a more personal frame of reference for each school.

High profile professionals may also serve as effective mentors and personal references. One of the advantages of working in a professional environment before attending graduate school includes making contact with these mentors who can greatly enhance your application with their personal recommendation. They may already have established a personal or professional relationship with faculty and administrators in the graduate programs to which you are applying and be able to connect you with influential members of each design school. These mentors may also provide valuable insight into the strengths and weakness of various schools, advise you on preparation of a design portfolio, and help guide your application process.

VII. The Statement of Intent

The statement of intent is an opportunity to tell the admissions committee something about your character, experience or ambition that may otherwise be difficult to convey within the portfolio format. The essay should serve as a personal proposal to each school. It is important to be open and honest about the reasons you wish to pursue a design education and why that pursuit is best accomplished at their institution. Cite your specific areas of interest, faculty members that you may want to work with, any courses within the curriculum that correspond with your interests, and how your personal background compliments each program. This portion of the application should humanize your presentation and illuminate your character. Tell the committee why they should invest in your education over that of other potential students. You are ultimately judged on professional character, academic achievement, design ability, and whether or not the admissions committee feels your goals are in line with the school’s agenda. How can they enrich you and how can you contribute to the discourse they are pursuing within the academic environment?

When presenting this personal narrative, it is important to keep within the essay parameters of each school. Admissions officers are often pressed for time and may not read the entire essay if it is too long. Most schools will ask for between 500 and 1500 words. The condensed format is just enough to open up a provocative dialogue about yourself, market your accomplishments and abilities, and outline some specific experiences that helped shape your character as a designer. The writing should be electrified with enthusiasm, confidence and candor. It is not advisable to detail your intended thesis dissertation within the essay as this may imply a lack of malleability. Leave the impression that you have an open mind to exploring new ideas and a capacity for reevaluating your own pre-conceived notions about design. While accomplishments and intelligent observations hold a significant value, each school wants to be sure they can open your mind to new academic experiences and show you new ways of looking at both the design process and the physical environment through the lens of their own curriculum.

Although this topic can be forever expounded upon, I hope this first installment of the series provides some insight into the presentation of an academic body of work as it relates to the pursuit of graduate education. Of all the choices we make as designers, selecting the most fitting course of education is one of the most important. Learning how to assemble your personal body of work into an effective visual narrative is the first step towards securing admission to any graduate program.

Jason Ivaliotis is a Senior Associate for the New York office of Handel Architects and is currently working on the design for two buildings in the Essex Crossing Development on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He began his professional journey as a designer and educator at Miami University in ...

18 Comments

Jason, this is a great overview of the portfolio and grad school application process! Thanks for writing this series for archinect.

Great feature - one question though. The size of these PDF's - is 97mb really necessary? Or is file size irrelevant now. I thought the PDF format was about file and size accessibility.

Obviously, the comment above is only relevant to emailed or downloaded work.

PDF File size is dependent upon the print quality setting in whatever program they were created. You can chose standard settings to have smaller file sizes or high quality to get the press quality prints with larger file sizes. Its common for final prints to be set to high quality before going to print which would increase file size. PDF's that are meant to be emailed would be set to "standard quality" or "smallest file size" but PDF's that are meant to be printed like these would be set to the best quality before going to the publisher.

Yes, aware of all of that. But you will notice that for these portfolios above, and in the discussions, there are some astonishingly high file sizes. In order to review them online, or email you dont need them that high. And arguably, you dont need them that high for printing either.

Great, great read. Really helpful. Will be referring back to this again and again the next few months!

hi why i cant download the file`s ?????????? everytime i click on it its do nothing save as not wokring also :/

This is obviously a fantastic resource; thank you Jason for taking the time to archive some invaluable advice.

Thank you for pointing out the incorrect links for the portfolio PDF files. This is now fixed.

keep them under 5mb for emailing/downloading. Have a hi-res backup for your own prints. Most places express no more than 2mb for job posts where they expect a ton of applicants.

Jason, thanks!

the architecture community doesn't have enough resources to guide noobies through some of these (what i would call) conventions. i know that i will be able to refer this to many of my peers!

Thank you Jason for taking time to write this article and share it with everyone.The work looks great and the article is so helpful to people in all levels of architecture.

I don't agree that taking a time off from school is a must. I think this advice is misleading, and I know many people including myself that haven't taken any time off and got accepted to all the schools that they applied to. I got accepted to Yale, Columbia, Harvard, and MIT, without taking anytime off, and have just graduated with masters from GSD and won the GSD thesis price for 2009. I don't think that it is a bad thing to go right after undergraduate, and I believe that people can decide for themselves- if they feel they're good enough and ready- I'll say go for it. Even though your article is insightful in many ways, your argument for taking time off is one sided. And you talk about it as if it is something everyone is doing and should do.

wow, the last poster has just proven the arrogant stereotypes of GSD students to be very true. this article seeks to provide helpful advice, it is not necessarily for everyone (no advice ever applies to everyone in all situations) and you've chosen to use this comment section to toot your own horn about winning this and that prize and admission. I think the point to take time off between schools is supported by some logical reasoning and whether you agree with it or not, there are some good reasons to take time off and develop your portfolio listed here...not to mention getting good professional experience between schools to expand your mind about the world outside academia and help focus your study in graduate school and become a better informed individual.

haha... all i'm saying is that the article or the advice is one-sided... i was just merely trying to show that you can either take a break, or not, and was showing supporting evidence for not taking a break. it had nothing to do with GSD or me. it's an advice- take it or leave it.

Thank you very much for your time.

I would like to see portfolios of those who do not have architectural backgrounds and/or those who have some background such as Interior Design...who are pursuing graduate school in Architecture.

This advice seems to be for MArch II. Any advice for MArch I?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.