David Maisel (b. 1961) studied architecture, landscape architecture, and photography at both Princeton University and the Harvard Graduate School of Design - before leaving the latter to pursue his photographic career full-time. He now lives in the Bay Area, and exhibits internationally.

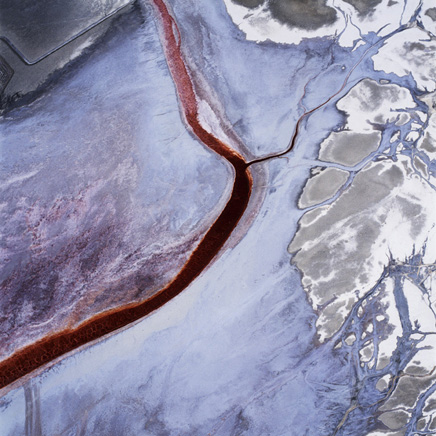

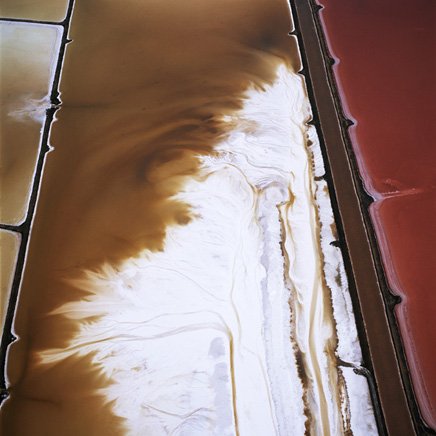

In his own words, David has a “fascination with the undoing of the landscape.” He has become most widely known for his aerial work, which includes extended studies of North American mines, clear-cut forests, urban sprawl, evaporation ponds and other peripheral industries of the Great Salt Lake.

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage

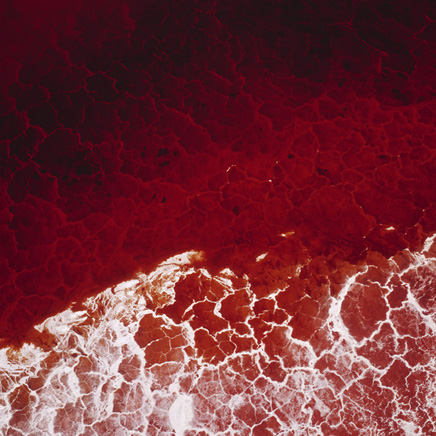

David has also produced a widely known photographic series of Owens Lake , California, with images taken from nosebleed-inducing heights as great as 13,000-feet. As cinephiles will no doubt know, Owens Lake was drained in the early 20th century to water the lawns of suburban Los Angeles (a notorious act of hydrological theft that found its way into American mythology through Roman Polanski's Chinatown ). Owens Lake is now a Dantean wasteland, one of the most toxic sites in North America.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

As Maisel himself describes it:

The only moving things are the dust devils that coalesce and spin in the afternoon heat, swirling white towers of cadmium, arsenic, sulfur, chlorine, iron, calcium, nickel, potassium, aluminum, chlorine. The lakebed emits 300,000 tons of such matter every year; thirty tons of it arsenic, nine tons of it cadmium. We had dreamed of building cities, fields of glittering towers, urban fantasies meant to house our hopes of progress; now we seek out dismantled landscapes, abandoned, collapsing on themselves. Rather than creating the next utopia, we uncover the vestiges of failed attempts, the evidence of obliteration.

David's work transforms human geo-industrial activity into something not unlike land art or earthwork sculpture - pollution as a form of avant-garde landscape design. Gardens of carcinogens. This comparison is made all the more apt by David's own photographic study of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty .

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage

When my wife and I stopped by David's studio to talk, it was on a day of unusually dramatic weather; rain fell from clear skies, and the temperature fluctuated unpredictably. His studio itself is in a nondescript, even abstract, complex of office buildings - marked by white numbers: 1, 2, 3... - a short drive from the waterfront of Sausalito.

Inside, natural light shines through a whole wall of windows, illuminating wheeled tables, desks, computer equipment, and bookshelves - which sag under the weight of books about Gordon Matta Clark, Olafur Eliasson, Lebbeus Woods, and countless others. David is jovial and friendly, answering the door with a grin, as if somehow amused that we actually arrived; we were comfortable the instant we stepped through the door.

David Maisel's studio

We stood, leafing through a huge stack of incandescently colored, archive quality, 4-foot by 4-foot prints of David's work, and had a lively conversation, covering California hydropolitics, the line between architecture and photography, "replicant" landscapes, the fate of human remains, Mars rovers, 9/11, and the aesthetic power of sterility.

Ӣ

I'm interested in the fact that you moved to California from the automotive claustrophobia of New York City. What inspired the move?

On some level, a move to the west in 1993 at age 31 was simply long overdue - I was born and raised in the suburbs of New York, and attended college in the suburbs of New Jersey, on the strangely artificial, neo-gothic campus of Princeton University. It was time to expand beyond the gravitational orbit of New York. I'd long been drawn to the scale of the American west, particularly since photographing Mount St. Helens in 1983. The spaces of the west seemed more raw and primordial, less civilized; the bones of the landscape are exposed.

Given my interests - in extreme scale, in boundlessness and formlessness, in desolation and landscapes of ruin - I felt as though I could not make work in New York, though other artists or architects with the same thematic interests might feel quite differently. Ultimately, the wholly urban environment did not feed me artistically, and a move west was part of a desire to be closer to subject matter that captivated me.

It strikes me now that the turning point was recognizing that I had a responsibility to myself to follow my interests, and to let my life take on a certain form because of those interests.

When you finished college, did you go straight to New York to make it as a photographer?

Well, I first moved to the Boston area. I started teaching there at a private high school, the Cambridge School. I ran their photography program, and taught an art history class that I basically invented. [laughs ] We looked at the history of landscape art, and we started with contemporary work and made our way back to the Egyptian pyramids. It was a very interesting school, very progressive. Even though I was probably closer in age to the kids than I was to the rest of the faculty, they were like a different generation. I was 22 or 23, and they were 15, 16, 17, but their ability to grasp certain cues from visual culture was really phenomenal.

After that, I moved to Maine, and for a year I lived on the coast. Basically, I built a darkroom and locked myself in it for ten months [laughs ] - and I highly recommend it! [laughter ] You know, in a way, that year in Maine was how I gave myself my own graduate program. Even though it was a very isolated experience, and isolating - and in some ways a very harsh thing to put myself through - it was very beneficial for my work. I gained a tremendous amount from it.

But at the tail end of that, I opened the door and I said: I have to go back to the world at large - and so I moved to New York. I went from living on an island that had no traffic lights to living in Brooklyn and working in Manhattan. It was an unbelievably intense shift. It wasn't a culture shock - but it did make me realize I need those two poles. It was swinging from one pole to the other that was actually the best thing for me. So living in the Bay Area ended up being - I don't know if compromise is the right world - but in a way it was the best of both. And yet actually neither. Certainly, living in the American west is better for me in terms of letting me think about and advance my work.

Did that shift in scale affect your interests and subject matter, or even how you thought of landscape?

I think not at all. I mean, who knows what would have happened if I'd stayed in New York, but what I found was I wasn't making work when I was in New York - so I would get on a plane and fly somewhere, you know, west of the Mississippi. [laughter ]

The work that I did in Maine, for instance, all came from the previous summer, when I had driven out west and done a lot of aerial work for the first time on my own. I was a year out of college. I did a tremendous amount of mining work - black and white mining work - and so in Maine I really had a project to chew over. That's what I spent ten months printing in the dark room. At the end of that, when the ground had thawed, I actually did do some aerial work in Maine, of some clear-cut logging sites, so... You know, I was already researching and following through on sites - and, obviously, Maine isn't the American west, but that scale was something common to my work both then and now.

David Maisel, from The Mining Project

I noticed that you're also a trained architect/landscape architect. Is photography something of a side-hobby that unexpectedly took off - while you secretly waited to return to architecture - or are you fully invested in the life of the professional photographer? Do you ever consider yourself a landscape architect distracted by his success as a photographer?

I spent most of my twenties moving between the practice/study of photography and the practice/study of architecture. I was fortunate to have studied as an undergraduate in an environment that made clear the possibility of considering both the built environment and landscape architecture within the photographic medium.

But my own work as a photographer didn't really come into its own until after I attended a year of graduate school in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. The architect Tod Williams had told me, before I returned to grad school, that my work in photography wasn't done. He was quickly proven correct! I abandoned the GSD after a year, because it was clear to me that I was more readily able to express my interests and concerns through the photographic medium than I could in architecture. I didn't have the patience to practice architecture as a young man; I wanted the immediacy of making things and of experiencing the world in its immediacy that photography insisted upon. Nevertheless, the two fields are finely interwoven for me, and my interest in them comes from the same place.

Have you ever been tempted to work in cinema, to treat landscapes as cinematic? Or do you think that the unmoving image is a more appropriate reaction to sites like Owens Lake?

I have been working lately in video; and I've recently completed a multi-media installation and projection piece of The Lake Project , comprised of still aerial photographs that are then choreographed together - overlapping, shifting, and bleeding through each other. I've collaborated with the sound artist Lee Pembleton on the piece. It was featured last fall in a solo show of mine, and the projection was scaled to fit the entire gallery, some 34 feet wide by 14 feet high. This scale is really the heart of the piece - to overwhelm and even subsume the viewer. But I think the refinement possible in a still image is pretty interesting. Not that film can't be refined. It's a language I've been working with for twenty years or more, so I do think it's possible to do something really remarkable with the moving image - even if I haven't done it yet myself. I'm not sure how I would approach it.

The impulse has almost been to go in the opposite direction and - when working with a moving image - to break things down, to have the components of the image be threatened in a way.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

It's obvious that your work is different from, say, Ansel Adams, yet his documentary-style “nature photography” serves as an inevitable point of reference for landscape photography today, particularly of the American west. You're not attracted to the same landscapes, for instance, and your technique - often using airplanes - is completely different from his. To my knowledge, there's no David Maisel series of Zion National Park, or of the Grand Canyon. Does straight-forward “nature photography” interest you? Does there have to be some kind of human stain or industrial intervention in the landscape before you remove the lens cap?

In Ansel Adams's era, I imagine that making such pictures meant something different than it would today. By now, this kind of work has been done to death, so to speak; I'm not certain there's much significance in making those pictures today - at least for me. I'm certainly guilty of it myself at times (I've been working in Iceland for two years, on a series of geothermal landscape images), but I actually find it somewhat self-indulgent. When I'm being particularly self-critical, I'll convince myself that making pictures of such “unspoiled” places doesn't teach me anything, offer me anything, or challenge me in any way, that it's at best a placebo. But I still have found Iceland, for example, to be an intensely captivating place to work... so it's a bit of a conundrum.

For the most part, I'm interested in landscape images not merely for what they look like, but for what they make us feel, and for what they might represent metaphorically. I've also wanted my pictures to take the viewer to places and sites they've never seen before, with a resulting sense of alienation or displacement. I'm less interested in being warm and fuzzy than in being harsh and cruel! [laughter ] Those possibilities don't exist when looking at the familiar.

So, the work I've made in Iceland, for example - the part of the work that seems to hold the most potential at this stage - is video footage of high-desert desolation, shot from a moving car.

Video?

Yeah. It's raw, and it's beautiful, and it's terrifyingly stark; it occurs to me that I am once again making images from a position that isn't fixed. So maybe that's my own predilection, and perhaps it's best to just give in to those, resign oneself to them, and see where they might take one's work.

I look at landscape from a conceptual point of view - it's fueled my pervasive interest in the work of Robert Smithson and Gordon Matta Clark, two artists that explored the undoing of things, the endgame, the absent, the void. I'm drawn to aspects of the sublime, and to a certain kind of visceral horror, and in a sense I am using my landscape imagery in order to get to that feeling, as much or even more than I am documenting a specific open-pit mine or cyanide leaching field or clear-cut forest. And I'll readily admit that my work may not hold up very well from a documentary standpoint.

In the era of Google Earth, TerraServer, and the like, aerial imagery is both extremely popular and the subject of intense academic interest. Satellite shots of New York City or Baghdad - even New Orleans: there seems to be a sense that access to aerial imagery democratizes geographic knowledge. What do you think of this growing popularity of the aerial image? Do you feel that your own work should be considered in this context?

The aerial view has certainly become, in our lifetimes, increasingly normative. The impulse is to assume that we understand or know something concrete about a place because we've seen a photograph of it, whether aerial or otherwise. I don't necessarily subscribe to that theory; information can be just that, dumb and inert: it needs tools of interpretation and discernment and judgment in order to have meaning. “Definitive meaning,” as such, is a slippery slope indeed. In fact, the slope is steeper and more treacherous now as the sheer quantity of information (from Google Earth , TerraServer , etc.) grows. To see a photograph of a thing is to see a picture of that thing, an interpretation of it, whether by the photographer, the remote satellite camera, or the viewer. The same aerial photograph of a flooded New Orleans may be interpreted quite differently by a hydraulic engineer, a former resident of that city, a member of Congress, or a pastor. There are multiple truths in images, but too frequently singular truths are ascribed to them.

I should add that I don't think of my work as aerial photography , or of as myself as an aerial photographer per se; it is simply a tool that I use in order to make the pictures that I want to make. That being said, I still recall first seeing the image of Earth that astronauts had taken from space - that sense of a fragile blue/green ball surrounded by blackness. I'm interested in the lasting strength of such an image.

It struck me while looking at your work, however, that even the word landscape is a bit inaccurate - the idea that you are a landscape photographer - because the sites you choose are more like events. Anthro-terrestrial events, so to speak. One could even argue that you are an event photographer, because you document abraded lake beds, forests being clear-cut, copper mines, and so on. What do you think of that? That a landscape itself could be an event, a process?

The word landscape is an interesting one - it implies a viewer who is making a judgment call. A landscape is bounded by our own set of interests and values. I mean, the land exists without us; the landscape involves our own discernment. So I suppose that you're actually very accurate. It's that sense of turmoil , or finding some... Really, it's the sublime, right? It's the dislocation of the viewer that interests me. It gets back to the same issue as Ansel Adams. I mean, I think that his work at a particular moment in time probably had a different meaning than it does now - but I want to make work that has meaning now . And I think you really have to be decisive about what that is - as an artist . You have an obligation, in a way, to choose subject matter that has meaning .

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage

You say meaning, but your own writing tends to have a more poetic than political overtone. Not that your writing is apolitical but it doesn't seem to prescribe anything, or make judgments. Does your work have a specifically political - even ecological - message, or do you see it as purely aesthetic?

I think there is definitely an ecological message there. But the issues are actually quite complex. The more I learn the less I know. The more I see the less I know. I think these are issues in which finger-pointing is really an easy reaction. Yet what I do feel is that we are kind of at the edge of this abyss [laughter ] - and I know I'm now falling back into poetic language - but that for me is the message that I want to tease out of these places. That's the continuity I think I bring from one area of subject matter to the next.

So we can drain as many lakes as we want, and we can pour cyanide solution over hundreds of thousands of acres of copper mine tailings - but we'll pay the price. I mean it's interesting, with The Lake Project , once the work was done and the book was out in the world, and there was a certain amount of attention paid to that work of mine, it was then that I met the head of the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District who really appreciated what I was doing. And he is the scientist and, sort of, activist, who organized a local group of citizens in the area of Owens Lake and became the David who slew Goliath in court. They sued the city of Los Angeles - and won. They're the ones who helped the court mandate this whole shallow flooding of the lake to keep down toxic dust storms.

So I have incredible respect for his work, and for his understanding of the complexity of Owens Lake. But he has an understanding; I don't, and I'm willing to say that I don't. I mean I could - I don't think it's an insurmountable lack of knowledge, or comprehension - but there are people who are better trained than I am, and who can make those calls. And I think, in a way, that the pictures aren't even necessarily suited to help make those decisions. They're using, for example, aerial photography now to survey the surface of Owens Lake in order to assess whether or not this shallow flooding is actually helping - and that's a different kind of aerial photography than I'm engaged in, completely! [laughs ]

I find - ironically - that your photographs make what happened at Owens Lake so beautiful that the images almost preclude an interest in intervening. Your photos aestheticize the abyss in such a way -

[laughs ] That's true.

- that Owens Lake might almost become a place of artistic pilgrimage, people coming to see what you call its “beauty borne of environmental degradation.”

Yeah. Yeah, that impulse interests me, too. These places really are off the beaten path, or are less-known, whether that's Owens Lake or the mining sites. But I do think that the more people start to visit them, or start to bring them into their consciousness, the better off we'll be. We'll have a better understanding of what happened in these places.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

Of course, the draining of the lake could almost be considered an act of avant-garde landscape design. I mean, one could easily imagine the lake having been drained for its aesthetic purposes: a conscious attempt to reveal the geochemical iridescence of the site. In an earlier email, you mentioned Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson's Green River project, which documents Eliasson's own intervention into the landscape (he temporarily dyes the rivers green). Your work does not entail that kind of intervention, however, where you make the site more polluted, more colorful, more inhuman or abstract. Are you ever tempted to cheat, to damage the landscape further, to poison it, infect it, before you take a photograph? To make things temporarily worse for its aesthetic impact?

Set fires in the desert so I can take a few pictures? You know, I've never had to. [laughs ] I've never felt that need. I'm not capable of that kind of nihilism, at least not yet! But I certainly appreciate Eliasson's piece. I've never been at a loss for... I mean, I'm more interested in the cumulative nature of small decisions. You know, I'm sure no one ever said, "Let's drain this lake and cause toxic dust storms. Let's get LA sued in the next 75 years." [laughter ] Yet that's exactly what happened. It was precisely un planned.

There are times that I've wondered what my next project will be, but I've never been disappointed in what reality actually has to offer. I suppose if I got to that point, would I start setting fires so that I could document the result? I don't think so. [laughs ] I don't think I could do that. I mean, how you arrive at your subject matter is a really interesting issue, and I'm really, really willing to be... to sort of fight for interesting subject matter and, not to be duplicitous at all, but to really use everything at my disposal in order to... you know, I'm not that good at sneaking in! And there are certain areas that you just can't sneak into. But I'll use everything at my disposal to help me get access to something I think may be interesting. That's more my style.

So an intervention by you, the artist -

It's not necessary. There are ways to achieve that sense of the base, the infected, the elemental without necessarily introducing poisons into the environment! For example, in my next phase of work at Owens Lake, I'd like to occupy a broader role as artist/sculptor/architect. My desire is to bring the viewer out of the gallery space and into the actual physical environment of the lakebed. My plans - quite preliminary and conceptual at this point - are to build two structures at the site: an observation tower and a footbridge. The observation tower, a spiraling, Tatlin-esque form, would rise on the edge of the Flood Zone. The Flood Zone is the most recent human intervention at the site, created to keep toxic windstorms from rising off the lakebed - like a replicant, a replicant landscape. It refers to the Owens Lake that was drained. It's got a sterility, a coldness, a machine-made feel that I like.

It's almost a simulation.

Right. But the footbridge would actually cross over the blood-red waters that remain in what was once the deepest part of the lake.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

Would that be for scientific purposes, to teach visitors about the history of Owens Lake? Or more of a landscape installation, an artwork of its own, a new Spiral Jetty?

I still think the net goal would be an aesthetic one. I don't see it as necessarily a place where knowledge will come prepackaged for you, the way many science museums do today. I think you could very easily, though, introduce viewers to some of the history of Owens Lake, and let them draw their own conclusions, assess the state it's in now. That could be a very interesting idea. But I also wonder if there's not a way for the architecture itself to suggest those things, without needing to spell it out. Maybe the thing I'm more interested in is asking certain questions, rather than giving certain answers. I'm very wary of being didactic.

But, you know that footbridge - if there was a way to have an oculus in the bridge, so you were actually looking down, and straddling the gap, and you're just suspended right above these blood red waters, you would come away with a different kind of knowledge, maybe not a quantitative knowledge. Maybe more qualitative . But you would have a knowledge.

You could do something with glass-bottomed boats. Take people out and punt around, like a Venice gondolier -

[laughter ]

- with Muzak piped over hidden speakers.

I like that. It wasn't until I finished the book that - it was only about a year ago - that I actually got down onto the lakebed in an extensive way, and it was with the head of the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District . So my views of the Lake are also expanding. I felt, when I was doing the aerial work, that it would happen eventually, that I would get onto the Lake, and so I wanted to do it in a way where I felt like I wasn't going to be sneaking around, or worrying if I was trespassing, or worrying if I might get stuck! [laughs ] That happens to people out there.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

Did you have to wear protective gear? Or masks?

No. Although if there had been a dust storm we would have wanted it. It was calm when I was there. But I guess these storms can come really quickly, and they can be pretty severe - headlights in the middle of the day kind of thing.

David Maisel, from The Lake Project

This is a fairly abstract question, but those colors at Owens Lake are fundamentally the result of chemical processes - yet so is photography. Your prints, for instance, are literally their own landscapes, made from the same metals present at the sites you've been photographing. So I'm curious if you see any connection between the chemical act of photography itself and those processes of landscape discoloration. Owens Lake, in other words, is a kind of massive photographic plate, producing abstract hydrological imagery on its surface, twenty-four hours a day. Do you ever feel like you are taking photographs - of photographs?

Yes, conceptually it is part of the work, though I've never heard it so poetically described!

On a similar note... I'm working now on a project called the Library of Dust , photographing individual copper canisters containing the cremated remains of patients from a psychiatric hospital .

David Maisel, from Library of Dust

The surfaces of these canisters are blooming with secondary minerals that are not dissimilar from processes I've photographed from the air. These vast and small-scale subjects share a sense of undergoing basic chemical reactions at the root of physical existence; I suppose the act of photography shares this condition as well.

That's an aerial project?

No, that's something that's not aerial, not landscape per se, and yet it addresses some of the similar questions of the sublime that I've been working with recently. The interesting thing with the Library of Dust is that I first learned about the existence of these canisters in March 2005. I determined what hospital they were in - which wasn't very clear to me - and contacted the director of the hospital, who I thought might have some reservations about my request to photograph these things.

David Maisel, from Library of Dust

But he's been very supportive, actually, and he shares my sense of... respect, really, for the subject matter, and how important it is for these images to be seen. Because the span of time that these canisters are going to be in this state is really finite, and the hospital is concerned that they're now basically corroding. So when I was there just a few weeks ago, photographing for I think the fourth time, there was a proposal being floated that each canister be put into its own individual plastic bag, and then each bag would go into its own individual black box that's made for containing human ashes. And that would be it.

David Maisel, from Library of Dust

To me, the arc of the project - if it ends like that, which it seems it probably will - has a certain kind of conceptual logic to it that I appreciate. I appreciate the form and the story of these canisters, that they're literally breaking down further every day, even between my visits to the hospital. My time of doing it, then, is finite as well.

Do you plan to photograph those final black, plastic containers?

I'd like to make a final overview image of the whole room at some point, in it's next phase. What's interesting about this whole quote-unquote library is that it was not that long ago that they started using these canisters. Interestingly, it was 1913 - which was the same year they started draining Owens Lake - and every effort was made to keep track of whose remains were in which canister. They started off using two different systems of paper labels, and those started off handwritten - then they were typed - and you can tell from the handwriting and even the typeface what era it was from. But most of the labels, 99% of them, are gone! So, incredibly, what remains is a number that was actually stamped into the metal at the top of the canisters. Then the question becomes: what of the book that keeps track of these numbers? What is it made of, and how many copies of it exist? It's a series of small, cumulative decisions, a bit like Owens Lake.

David Maisel, from Library of Dust

So all of these attempts in less than 100 years have become languages that we can't work with anymore. In many ways, I think that's why I feel so protective about the images - and why the hospital, especially, feels so protective over the canisters themselves. These really deserve respect; they're not eternal. Even the black plastic, you have to wonder, how permanent will it be? Though the proportions of the boxes seem a bit like the obelisk at the end of Kubrik's 2001 .

There is something about dust - that permanent state of dust - that is really interesting to me, and I'm seeing it percolate through my work in a bunch of different ways. You know, a couple weeks ago there were those NASA scientists who got some space dust, and they brought back to earth - it landed on the salt flats in the Utah desert - and they've been examining it, and there are actually particles that are visible to the naked eye! They thought it would be - you know, by necessity - viewable only through a microscope.

But there's something about the limit of human vision - that dust is this thing that... that you can maybe see a speck of dust, and then anything smaller is... There's something about that that's really interesting to me. It occurred to me that at some point I should probably try to gain access to photographing either the dust, the cosmic dust, or more likely the apparatus that surrounds the ability to look at the cosmic dust. Because I'm sure there are some quarantine issues, and things like that, that could be very interesting to look at.

Maybe one of my projects [laughs ] - you know, years and years ago, a friend of mine said: if you could photograph anywhere, where would you go...? And my response was, you know, I'd go to Mars! [laughter ] And he said, well, you just have to keep going to the right cocktail parties, and I'm sure you'll find a way to get there...

You could join the next rover. The world's first Martian landscape photographer. If Mars has landscapes - not just land, as you phrased it earlier.

Yeah. But those images, that are coming back now, they're fascinating. Fascinating.

As far as your next project goes, is that the Iceland project?

The Iceland material is interesting because I started shooting there in 2004, and then I went back last summer - so it's been two summers in a row now I've been there - and it's the kind of place I think I'll return to for just years and years and years in order to continue this sort of... very long investigation. But I don't really know yet. I haven't made a single print of anything from Iceland! [laughter ] I haven't really pushed it into form yet.

How did that first trip come about?

I've always had an interest in Iceland, because of the volcanism, but then there was an article in The New York Times, I think in 2003 - front page - and it was talking about an area in the more remote, eastern part of Iceland. They were considering building a dam there that would be a power source - you know, Iceland doesn't need more power, they have more than enough, just geothermally, for themselves - but they were considering opening up to international development in a way they hadn't done before, so they were considering a proposal by Alcoa to build this dam in order to supply power for smelters and things up there.

The image they used really interested me [laughs ] because it was this canyon - I think it's called Black Canyon, or Black Rock Canyon - and there was a little speck in the center of the canyon, and I realized that it was actually a Cessna! And there was something about that scale-shift, this tiny little speck, that makes you realize how phenomenally huge the area that they're talking about really is - that really captivated me. So I cut it out, and I thought: okay, I'm going to do a before, during, and after project in this region.

So, summer 2004, I finally get there, and I actually got access to the construction site of the dam - but I missed the before, completely! It happened so fast! When I was reading about it, it was just a proposal! But when I was there I was basically given full access to photograph everything going on, and so there are a lot of images there that interest me - again, this kind of dismantling of the environment. But when I went back last summer the political climate had shifted and - whereas in 2004 they were very proud of the work they were doing, and they were interested in giving access to a photographer - a year later, when the construction of the dam was well underway, then the protests started in Reykjavik, because they realized that - I mean, I guess there had been a real fight to keep out this development, but the government decided in favor of it. So after the government decided, I think the need to fight it fell away. But as the development actually started, or intensified, there were more and more demonstrations, and there were these... events where people would chain themselves to construction vehicles, things like that.

So, at any rate, the climate had shifted and there was no way that I could get access again! [laughter ] The thought that I had then, perhaps, was to shoot from the air next time, so I'll have to plan a little better for that.

David Maisel, from Brief Encounters , featuring a Canadian hydroelectric dam

The little airplane reminds me of your flights over Los Angeles for the Oblivion project. I'm interested in your discussion of paranoia in the context of Los Angeles - particularly, LA as seen from the air in a post-9/11 era. That same photographic technique, however - the flying, the angle, the bird's eye view - is used in The Lake Project, even in Iceland, yet there's no mention of paranoia there. To what extent do you think that the (invisible and indirect) presence of human beings is responsible for generating Oblivion's sense of dread and impending disaster? Is it the presence of urbanized humans, in other words, that gives the images their psychological depth?

Well, the Oblivion series was actually a sort of coda to The Lake Project : what did the demise of one environment permit to come into being in another? By chance, that project was realized in a post-9/11 time period, so seeing the urban world from the air simply was not the same as it might have been a few years earlier. Getting permission to fly over the city was fraught with difficulty; the possibility of an airplane somehow turning the urban fabric into the site of an Armageddon-esque conflagration was implicit.

David Maisel, from Oblivion

At the same time, the meaning of “looking” within an urban environment has changed; it's now more akin to an act of surveillance. Who gets to look? Who controls the gaze? Who controls the information seen? Who is or is not permitted to photograph the railroad tracks, the subway station, the public building? Is it unlawful to do so without permission? And who, or what entity, is given the power to grant such permission? By what authority is that bestowed?

David Maisel, from Oblivion

In a post-9/11 world, there's a kind of paranoia (perhaps not unduly justified) that what we have created (our cities, our culture, our homes and our lives) can vanish in an instant. In one afternoon. As a country - in the not terribly distant past - we've found reason to obliterate entire cities of our wartime enemies with a single blast; the felling of the Twin Towers on a beautiful autumn day indicates that much the same is possible within our own borders. It is the necessary coexistence of such fears with the mundane aspects of everyday existence that I find compelling at this point in our country's history. The threat of death is ever-present in one's life; the terrorist attacks on our country seemed to bring that realization home in a new, and chilling, way. One could argue, as well, that the government has had a hand in using (or elevating) that paranoia to its own code-orange state.

David Maisel, from Oblivion

I suppose these are all elements at work for me in the Oblivion images.

Of course, Oblivion is black & white - even reversed, or negativized. Is there something about the familiarity of the urban landscape that caused you to react this way - reversing the image, distorting it, making it unfamiliar, even sinister? Threatening the image, as you said earlier. Why did aerial photographs of LA in particular inspire you to manipulate the image?

While viewing the negatives on my light table, I started to consider the negative itself as a complete image, aesthetically, and so I began to print the Oblivion series that way. The negative is the essential photographic image. It also moves the series away from the documentary and into a more metaphorical realm, into a shadow city; the images have a quality of a post-nuclear blast, an x-ray quality. They turn the city to ash. They also remind me of those old-style blueprints architects once used.

At the same time, I began to think of the elements tying my work together over the course of many years and many cycles of different projects - Mount Saint Helens, Owens Lake , even the Library of Dust - and I realized that there was a common thread of looking at ashes and dust in different forms.

David Maisel, from Oblivion

Changing the subject a bit, have you ever considered producing images as intentional illustrations for someone else's text? A new translation of Dante, for instance, or a new Paradise Lost, featuring photographs by David Maisel? Or some other text that interests you?

Hmm. That's a very interesting idea. Yeah, I certainly use literature. I use it to help me think about my work. I use it to help me think about the subject that I'm looking at, and I think those kinds of pairings are very interesting. Whether illustrate is the right word... It would be a real challenge to work from a specific text. I've never done that. I mean, there are texts I've read that I've had in mind as I'm making pictures, and I do think that a poem or a piece of writing - the right text - can help establish the mindset that a viewer brings to them. The Lake Project book has a really beautiful essay by a curator, Robert Sobieszek, who just died last fall. Even his text - it's an essay, not a poem - even that text I thought gave the viewer a certain kind of stamp to work from. I love the idea of collaborating with writers, though, it's a very provocative idea.

Any writers in particular? Or any text? Top three?

I'll have to think about that. I think J.G. Ballard has been - I keep coming back to Ballard, over and over again. So that's one.

Which Ballard?

The Drowned World . But there are books that I keep on my shelf, and that I sort of come back to, like Borges - Labyrinths - or even this book, The Shape of Time , by George Kubler. It's a theory book; it's not a poetic book. Then these past couple of years I've been interested in Anthony Vidler's writing. He's really an architectural theorist, but -

What about the Romantics? Or the sublime? Poetry, ruin...? Have those influenced your sense of landscape?

The sublime has been a very active influence - from Edmund Burke, Caspar David Friedrich, NASA images of space, through to the abstract expressionist and color-field painters, and through to the contemporary work of Bill Viola. In terms of writers: the symbolist poets - Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Valéry - and especially the work of Wallace Stevens. His essays on reality and imagination called “The Necessary Angel,” in particular.

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage

Do you ever read John McPhee?

Absolutely. Yeah, McPhee is interesting. I never took a class with him, but he was teaching when I was an undergrad at Princeton, so his influence was kind of percolating through the undergraduate zeitgeist in a way. Also, as an undergrad I worked with Emmet Gowin, and there was actually a link in their work. I don't know how well they know each other, or whether they've ever collaborated, but their presence really formed a background at an early stage for me.

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage

Similar to McPhee, in some ways, most of your work is set in the United States, or at least in North America. I'm curious if you have an interest in other sites of manmade natural catastrophes, so to speak, that are not in the U.S. - or on Mars -

Absolutely. I do. I definitely do. I think that has largely been a matter of access and financing, as opposed to lack of interest. I have notebooks where I just pull things out of the newspaper - they're almost like scrapbooks, they're fairly random - and then there are other things where I make files...

Which you keep in notebooks?

[David opens a low, black filing cabinet; it is stuffed full of unorganized clippings, on top of which is the Iceland article. We look at the pile of papers, a second passes, then we all laugh. He closes the drawer. ]

Any place you want to go in particular?

No, not yet. I mean, there's mining stuff all around the globe. Some incredible sites in India that I'd like to get to. And also in South America. But in a way that's how I got to Iceland.

Finally, how do you know when a project is finished? Do you play it by ear, are there objective standards, subjective expectations, anything to which you try to conform?

I don't think I'm ever really finished with most of my projects. They might get to a certain juncture - a book or an exhibition, for example - and I may move on to some other series after that; but I always feel that I may return to something at a later date. I am forever photographing mines, though the “mining project” as such mostly dates from the late 80's through the early 90's.

There's a randomness to it. But then there's a spark - and you follow something through.

[For more information on the political history - and chemical future - of Owens Lake, visit the Lake Project , a public art project that uses David's imagery. Meanwhile, a fascinating account of American hydropolitics (including the story of Owens Valley) can be found in Marc Reisner's excellent Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water . For more information about David himself, be sure to visit his own website ; alternatively, a short article of mine, about David Maisel, will appear in contemporary within the next few months. Also, David's photograph of Smithson's Spiral Jetty is available in a fantastic, wall-sized vinyl banner from BetterWall ; and his Oblivion series was recently posted on Polar Inertia . Finally, David has an active, international exhibition and lecture schedule for the remainder of 2006, including stops in Daytona Beach (24 February-23 June; lecture on 29 March), Frankfurt (7 April-21 May), Toronto (29 April-29 May), and the International Center Of Photography's Triennial in New York City (8 September-26 November; lecture on 22 March). Stop by, say hello - and tell him you saw his work on Archinect.]

David Maisel, from Terminal Mirage and The Lake Project

David Maisel is represented in New York City by the Von Lintel Gallery , 555 W. 25th Street, New York, NY 10001. Additionally, Maisel is represented by four other galleries in the U.S. and abroad.

Geoff Manaugh is an editor at Archinect . He is also the author of BLDGBLOG , and of a novel, called Film Night . Geoff sincerely thanks David Maisel for his patience, time, and enthusiasm in seeing this interview through to publication; Joseph Antonetti, for assistance with images; and Nicola Twilley, for her friendship and invaluable support.

16 Comments

Fantastic interview & images - thanks Geoff.

No problem, el jeffe. Glad you liked it. Maisel's an incredibly interesting guy.

And as a kind of note to everyone: we've got larger versions of the images that will go up soon, so a week or so from now check back; there will be slightly larger versions of all these up for your viewing pleasure.

Also, anyone in New York City: David will be speaking at the International Center of Photography on 22 March... which is tomorrow. Tell him Archinect said hello.

great interview Geoff. you are incredibly thorough in your format...thanks for putting in such an effort.

Nice interview Geoff. Very thoughtful - does justice to Maisel's amazing body of work. Great choice of images too!

parts of this are reminiscent of James Corner's Taking Measures Across the American Landscape.

really fascinating stuff (Maisel)...incrediblly indexical - his desire to see things through various stages......and I thought: okay, I’m going to do a before, during, and after project...

Glad you guys like it. Now I should do a before, during, and after interview...

wow.

great scene.

Oddly enough, you can read about those copper canisters on Boing Boing...

And now David, too, is <a href="http://www.boingboing.net/2006/03/21/portraits_of_cans_of.html">on Boing Boing</a.> (Thanks, Neddal [and Ken]).

Oops: try this link.

was a crazy fello... painter then painter now.

Maisel`s works are just too interesting!!

Geoff- That surely was a well thought, a well laid interview.

Such interviews focussing on creativity and the power of such ideas other than works of architects and their firms alone are very much appreciated. I think it should surface time to time.

Cheers.

Chameleon – thanks!

Meanwhile, a massive article just appeared in the LA Weekly about the draining of Owens Valley – who's responsible, who isn't, what happened, what didn't. First two paragraphs:

"Beyond the arid vacancy of the Mojave Desert, U.S. 395 enters the austere majesty of the Owens Valley. To the east are the reddish peaks of the Cosos. The snow-covered Sierra Nevada rise along the western side. For miles ahead, the view seems endless, except for the Inyo-White range, which curls around the northeast edge of the valley. This is one of the good days, when the air is clear and crisp.

"Midway up the valley, near the town of Olancha, lie the remains of Owens Lake. Back in 1904, immigrant water baron William Mulholland arrived here with Frederick Eaton, the retired L.A. mayor and water hound. They had ambitions to solve a drought and expand the city into the San Fernando Valley. In seizing their prize they could not have pictured the destruction they would cause by diverting water to Los Angeles."

More: LA Weekly. (Thanks, David!)

Fascinating!

very intriguing!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.