"It’s a practice rather than a religion, but the practice is essentially living by principles and then meditation," states Michael Rotondi. "It’s Buddhism without beliefs, I guess would be a way to look at it."

Currently the principal of RoTo Architects (among other roles with the firm's sibling studios), Michael Rotondi has worn many hats throughout his career. For sixteen years, he worked with Thom Mayne as a principal at Morphosis. A founding member of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Rotondi later became director of the school, serving in that capacity for ten years. In 2009, he received the AIA/LA Gold Medal and, in 2014, the Richard J. Neutra Medal from Cal Poly Pomona College of Environmental Design.

Rotondi is also a man of deeply-held spiritual convictions. He says that his spiritual journey led him out Morphosis, directed his directorship of SCI-Arc, and continues to play a primary role in his work as an architect and as an educator. I talked with Rotondi over the phone to hear more about his spiritual practice. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you develop your spiritual practice?

Well, about 25 years ago—at least 25 years ago—I decided to reconceptualize and restructure my life. I was beginning to question lots of things with life. Not that anything was going wrong, in fact there was lots that was going right, but I had a longing for something deeper than just intellectual practice. My quest was to first go to Indian country and spend a lot of time reading Native American texts in the location that they were describing, so the fact of the physical geography and the fiction of the kind of narrative and the spiritual geography. And then I was hired to go and work with the Lakota in South Dakota, where I spent seven years going back and forth working with elders, medicine people, as well as educators, to help them with what I thought was initially just to rebuild their university—the first tribal university in the Americas—but what I was really searching for was any societies that had worked hard and long at achieving a total integration of both spiritual practice and intellectual practice. That’s really what I was longing for. I wasn’t looking for another religion, I wasn’t looking for a guru. I was trying to figure out how do I reconnect my heart with my brain. Because architecture is intensely not spiritual in any way.I was trying to figure out how do I reconnect my heart with my brain

Could you elaborate?

Architecture is an intellectual practice, and what I discovered at the time was you can’t even mention the word ‘spiritual’ the further east you go. You can get away with stuff in LA, but when I started moving east, as soon as you leave Denver, all of a sudden you had to go from spiritual to metaphysical, you know? And that really surprised me a lot. I’d been around students my whole life and there’s an identity crisis when people get into university. I’m generalizing here, but the same way what’s considered the terrible twos aren’t the terrible twos—that’s the first period when you’re starting to develop a sense of yourself—but you don’t know how to process it so you’re flailing your arms and your legs and if you don’t have understanding parents or siblings, you basically get in trouble a lot and it makes you go weird.

When you reach adolescence, you have no parents, and that’s another way of establishing identity. There’s a number of milestones in between but the next big milestone is when you get to university and you start to become really really smart and you move everything in your head for all the good reasons, to develop intelligence and hopefully a measure of consciousness. There is no God—I was opposed to that—and I was raised in [parochial] school until finishing in the seventh grade. Then I went to public school because I just wanted to go to public school and convinced my family to let me go to public school. But I thoroughly enjoyed the mysticism, the rituals and sort of being in service, so to speak, for about four years or five years. I was what I call a varsity altar boy. I had calculated that I had gone to mass, I had served and gone to mass about 1200 times in four years.

I was the same, funny enough.

Yeah, I loved that. You goofed off a lot, like the first thing you do is you eat the wafers and you find out that it does not burn a hole in the top of your roof, you know? And then we’d serve the pastor the chalices that are used for the high mass at the low mass at 6:30 in order to see how quickly he’d get drunk. So, he’d always request us! I’d always volunteer to be the one in any of the processions, the one that was holding the incense burners and I would put too much incense and then move it too fast and smoke out the church, and you heard people coughing, it was like a scene out of a movie. And then, you made friends with the other altar boys, so there was that kind of stuff going on.

I really loved this ritual, and I guess that’s why I still to this day see movement in a building, not just as circulation, I see it as procession. How do you approach a building? What does it sound like when your car stops? And when you get out? What is the first step down? And then the progression from the car to the building? Is it done in a conscious way? Usually it isn’t, but they are the little things we consider. You can look at all ecclesiastical work and it has that in it.

Anyway, I’d reached a point where I just wanted to integrate my heart and my mind. And then I wondered who else does that?

I still to this day see movement in a building, not just as circulation, I see it as processionI started off in Indian country. [Then I discovered] Thomas Merton and I was amazed that this monk that got up at 3:30 every morning was so prolific. Like a lot of people, [his work] just resonated because it made sense in the context of my Catholicism as well as how he was able to take the traditions and scriptures of Catholicism, Christianity, and move it [towards] the Eastern side. Because no one had ever done that at school, no one had ever looked in a more economical way at all the religions and helped us understand it culturally. It was always ‘there’s a good religion, there’s a bad religion, these are getting into heaven, these are getting into purgatory, the rest of you can go to hell unless you do something on earth’ and all of that. Anyway, reading Merton was a huge help.

Then, by what I call psychic marketing, I was invited to go and work on an Indian reservation with the Lannan Foundation. Why? I don’t know. I think I actually knew why, because there weren’t a whole lot of architects around who were also educators, who had aspirations to work at a high level and that were also working in a positive way with a spiritual conflict, if you will. I wasn’t conflicted spiritually, I was just conflicted on how to integrate spirituality back into my life.

Three years after the process began I got a call out of the cold from two people who had started an American Buddhist movement in America: Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg. It was really a bit of great fortune and it could be that it’s serendipity, but that’s when I started to really think about what eventually became understood by me as good as having Wi-Fi—way before computers ever did. We know that when somebody who you’re really close with—it can be a sibling, it can be a mate—that you look at each other and you don’t even have to speak because you’re both thinking about the same thing at the same time.

That happened to me in the gardens of Kyoto, where at the turn of the season, at the turn of the day, at the turn of the temperature, I’m doing the tea ceremony with a tea master because I want to know what the experience is like. We both look at each other at the same moment because I want to say something to her. She had experienced exactly the same thing, we both smiled, she said, ‘That’s what we call speaking in silence.’ That’s what the tea ceremony is about.

How did these experiences affect your architectural and educational practices?

I started to really wrap my mind around the limits of architecture based on how we teach, how we practice, and what we are. I didn’t know what was going to happen. At that time, I decided to dissolve a marriage of 22 years, dissolve my partnership with Thom [Mayne] and to move higher. At the same time, I was directing the school and I decided that everything had to change, including SCI-Arc. I had to go to a new location [...] So I said, ‘We’re moving’, and we went through a few months of discussion and debate until finally everybody decided.

You know what really got everybody to say yes? It was really funny, it wasn’t my persuasiveness. We had all-school meetings still, in those days. I set up what I would call an executive system based on parliamentary processes and so what that means is one person makes the decision but before he makes the most important decisions, you put it out to the crowd and everybody gets to weigh in. And it’s feedback, people don’t get to vote, so it was executive authority in that regard, but it’s more benevolent than doing it [entirely] based on your own wishes.

Anyway, so somebody in the crowd asked, “Why do you want us to move? Why should we move?” And I say, “Well, okay, why should we stay here?” And then another—I don’t even know who said it—coming in from the corner, it was silent, and somebody said, “Because we’re comfortable here.” And then there was a dead silence, and another voice came up that goes, “Ah shit, we’re moving. We’re moving.” I said, “Exactly. Exactly, we’re moving. Comfort is the death of us.” So, we moved and the students helped us move [...] I got us some budget to rent a truck, went back into the coordinating position and over four days everything was loaded on the truck and we moved from Santa Monica to Culver City.

You delude yourself into thinking that what benefits you benefits othersIt was a clean sweep, wondering whether or not I could get my identity back after 15 years at Morphosis and wondering whether or not I could ever love again, after dissolving a marriage that had gone a little bit dry for the last five years, and whether or not the school could ever get back to pull its grade. And what I really believed is that in order to grasp something new, you’ve got to let go of what you’re currently holding on to, at every scale, and I started to see that and understand conceptually that we’re really radical. Conceptually we take a lot of chances. But we don’t live the life that we expect others to live in the projects that we’re designing. And I said, “That’s not fair, that’s really not fair.” The ultimate test is whether or not I could survive putting myself through the kind of change that I expect others to go through. [...]

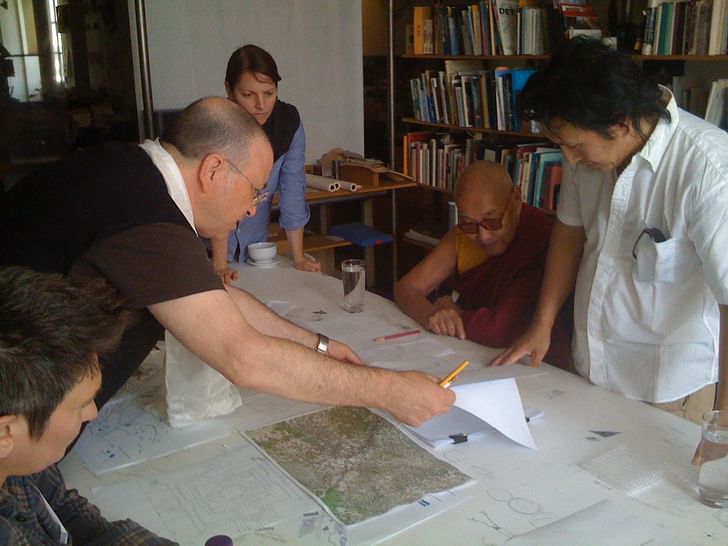

You delude yourself into thinking that what benefits you benefits others so there’s that other conflict which I didn’t thoroughly understand until I started turning to Buddhism and American Buddhism. I asked an American Buddhist, is there any monk I can hire for SCI-Arc, and they said, “Why?”, and I said, “Because I think it would be great to have a monk teaching a theory seminar at SCI-Arc”. And then a monk shows up who wants to be an architect—I mean what are the chances of that? The only Tibetan monk who’s an architect in the community—maybe there’s another one at this time—ordained by the Dalai Lama, in the Dalai Lama’s monastery in Dharamshala. He asked if he could come to America to learn English, enrolls in Santa Monica college, gets an AA degree and he’s going for a second AA degree and when I meet him I say, “You can’t get a double A degree,” and he says, “Yeah, but I’ve got nowhere else to go,” and I said, “Come to SCI-Arc, I’ll waive tuition, I’ll give you one class each semester to teach, you can be an advisor to me.” It turns out he was a Buddhist scholar. He had the equivalent of a PhD even though they don’t have degrees. We converted to see if he could qualify for graduate work and it turned out that he had the equivalent of a PhD in religious studies. He never uses the pronoun ‘I’. It’s the most astonishing thing.

Anyway, so I got him to SCI-Arc. [...]

How would you say that this spirituality has changed the way you approach designing a project?

I don’t come to conclusions, even though I see things quickly and the objective isn’t to come to closure. In game theory there’s a finite and an infinite. In the finite, the rules are set to bring things to closure, and somebody wins and somebody loses. In an infinite game, things can come to provisional closure but they keep on. The rules are setup to keep the game going.

As a child I played a lot of ping-pong, a lot of table tennis and when you are in competition you basically play a finite game but when you are playing with friends in order to get better and better and better, you play the infinite game. So, when I’m approaching a project, I have begun to understand that you can still operate with a sense of urgency but guided by a long-term vision.

I don’t come to conclusionsI was just asked that a little while ago, I did an interview for a project, and they were asking me that question: “What makes you the best, what makes you good, what makes you feel…?” And it really has to do with seeing myself now fundamentally as a teacher. I also practice but as a teacher it doesn’t mean I’m professing. A teacher for me has to do with having the highest degree of tolerance and patience and open-mindedness in order to let things in that you might not have heard otherwise, even from the innocents who may not be expressing it in the most coherent way. Then you begin a process of absorbing whatever it is you heard into your own life in some way.

With architecture, it has to do with absorbing what other people are saying or not saying. Then you can intuit and bring that into the work and then putting it back out again in ways they couldn’t have imagined. Sometimes you can’t speak about it because they think they just hired a guru instead of an architect, but I think it’s a capacity of patience and open-mindedness and then wanting other people to see what I see, not trying to always impress with how much I know and how good I am. It has to do with my relationship with other people. Then the same fairness that I try to understand and enact between people I begin to see between materials on a building, and the way details come together, and so it has shifted me radically from the time when you pretend you’re mean and angry and you’re making buildings that can cut you like a knife. You know, you make things that are going to shock you and scare you. It wasn’t about that. It shifted my view from the motivation being fear to the motivation being love. Not romantic love, but going from anger to joy, basically.

You started talking about this at the beginning, but did you find that when you changed perspectives your relationship with the local or larger architecture community changed? That you were no longer speaking the same conversation with them?

Yeah, I mean I’m able to delegate, I can shift conversation, but I can be able to extract it from anybody but I wanted to be consistent so—how old are you now?

Twenty-five.

Okay, still quite young. I would guess that you have a variation on your personality depending on who you’re hanging out with.

Definitely.

You know, you could be hanging with your really smart friends, you could be hanging out with your family, you could be hanging out with your college friends, you could be hanging out with buddies from the neighborhood who are on the verge of going to jail—whomever—you’ve got variations on your personality. I started to realize that it takes a lot of time to remember. It didn’t make sense to me at a certain point in time, to have variations on my personality. I realized that that was another kind of soft fear, a fear that I might be rejected, or I might be foolish, or I might be misunderstood.I decided to integrate my personalities

I decided to integrate my personalities and the way I look at things and the way I talk about things. I said that the one thing that I have to be really clear on is that I’m not afraid of making a fool out of myself. So I started lecturing in public about things that I was discovering within myself, and my lectures changed. My lectures changed from showing people how much I’d done and how good I am to things that I believed they already knew that they might be able to get back together if I taught it, or to rediscover by the way I talk about the ideas that are in the work and the way I get to the work. So instead of just showing projects I showed everything but projects. Then I began to break up the projects, instead of showing the project in total.

Anyway, so I consolidated all of my personalities into one and then I just began talking about whatever I was talking about. When I look at my sketchbooks over the last 30 years, there’s a lot of the same things I was saying then that I’m saying now, but I’m saying them with more insight and more sophistication because I’ve been thinking about them for so long. [...]

Do you think a space can be designed to inculcate a specific type of experience?

Yeah, I think so. I mean that’s what April and I attempted that 20 years ago when we bought Miracle Manor, the motel out in the desert. We wanted to see if it was possible to develop a total aesthetic instead of just a partial aesthetic. A total aesthetic starts with the base and the light and the color of the light. We immediately realized that, in order to achieve this, in order to get a total aesthetic, we can’t privilege the eyeball. So we’ve got to make all the things that we do have to be less than visible. You’ve got to look twice in order to see things once. What that leads to hopefully is that the design is transparent to the experience, so that everything you’re making becomes a lens through which you look, and it’s a portal into other worlds, it augments your imagination, it augments your intuition, it enhances emotional intelligences that are starting to come out. So, it was doing what the desert would naturally do anyway if you weren’t in a building. When you’re hanging out in wilderness, you basically open up.The only way you can work on selflessness is if you don’t market yourself

That’s why we kept it all these years: to make [such an experience] possible for others without ‘profitizing’. Giving them the opportunity to get in touch with themselves in ways they’ve never gotten in touch with themselves, and not using it as a vehicle for more work or for any kind of notoriety. That’s why we’ve never published Miracle Manor and this why I stopped publishing 10 years ago. This is why I stopped entering awards programs about 10 years ago. Because I was working on selflessness. The only way you can work on selflessness is if you don’t market yourself. It’s a bad idea for business but a good idea for self-development and it’s a long-term play.

It’s to see if it’s possible for me to survive, to practice, without doing all of the conventional things of promoting yourself. Instead, just [getting work] through word of mouth, work begetting work, and psychic marketing. You survive and things show up. [...] I’m interested in trying to incubate the careers of the people that are here now and help them develop notoriety and me being like a mothership without needing any credit, I don’t need any fame. I need a bit of fortune, but I don’t need any fame. [...]

It seems like that way of thinking really sets you apart from the main paradigms of today, the privileging of self-promotion and branding—something like a cult of the individual. Do you think that you are like a lone voice or do you think that people are coming around to thinking like you?

I don’t know that anyone is coming around to anything I’m doing. I do know that the deeper I go into myself the more connected I am to other people, and I know that I meet people who might be a certain way, that way begins to go into suspended animation for the time that I’m present, and that’s not out of fear, it’s out of them getting in touch with some side of themselves that they see present in me, that they aspire to themselves, even though they may not stay there very long. I don’t expect there to be great changes in anything. I think that just by my presence I might be able to help people get in touch with their lighter side, rather than their darker side, and that’s really what I’m hoping to do.

What is always hard to figure out is do I work on myself or do I work on the world?

What you learn from the Buddhists, the Tibetan Buddhists in particular, is that you work on yourself first and foremost because the healthier you are the healthier you are going to make everybody in your sphere of influence. I thought, “My God, that’s it, why didn’t anybody tell me that when I was a kid!” It’s not just working on yourself to serve yourself, you’re working on yourself to serve others. It sounds like an oxymoron, but that’s the way it works. [...]do I work on myself or do I work on the world?

Most importantly for me, architecture is a pretext for the relationships that you can begin to construct and develop over time. Life is one architecture in my world. No longer is architecture giving form to life and it doesn’t preclude still having the high times that I had when I was 25 or 30 or 35, it just means that the way I see the world and I see my role as an architect and the role that architecture has in the world is much different. I think architecture can enhance and augment the greatest products of ourselves. It’s not just privileging the eyeballs because the eyeballs go immediately to the brain, and the brain is the conceptual tool. Anything that doesn’t know any gravity, it has great great value because you can go to the end of the universe and back but the fact that it’s not grounded, it doesn’t always speak true, you know? The body never lies, so it’s not one or the other, or one against the other, it’s putting them both together. The brain is theory, the body is practice. Imagine a world without both simultaneously. Imagine a world with both simultaneously and that’s really the what the question is.

I may not be able to achieve it in my lifetime but it’s possible through the mentoring that I do through school but even more with the mentoring I do here in the office that some of these people might be able to realize the aspirations that I have over had the last 45 years. That’s all of it in a nutshell, Nicholas.

Thanks Michael.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: [email protected]

56 Comments

^yet we can measure and observe the expanding ripple from said "finger snap".

... and it's still a far more intelligent line of thought that a murderous and rappy bearded man propped up by a hoard of pedophiles and texts so blatantly false.

As mr. Sagan famously said:

"It is far better to grasp the universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring. "

Agreed. But I do not assert there is no such character, I simply say there is not enough evidence to believe there is. I believe Mr. Sagan was also pointing out that reality is amazing and worth investigation and not less amazing than any story one might tell today or in the past. But the main issue to this original discussion is not whether or not there is a God. The first, main and only point was my original assertion that there are small fallacies in statements like, "I do not come to conclusions" and "connecting heart and mind" when describing a design process in the context of an educational environment. This seems to me counter productive and harmful to the profession. I do not encourage , accept or condone attacking people for their beliefs. I do feel it is acceptable to call out bad ideas and muddled thinking when it come to the profession, design, architectural education, and mentoring. I simply ask people why they say these things, and call them out as false. If more muddled thinking comes back as a justification, I do get condescending. That is a weakness of mine. I apologize to Donna as I had suggested she go back to school and as a person already clearly educated, that was in her words, mansplaining. I deny doing that as it seems to require gender to come into play. But if it means any man being condescending, then yes I was mansplaining. It is a weakness of mine, but stronger language is often required to get through on important issues.

Non- guess who came up with the big bang - Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître (French: [ʒɔʁʒə ləmɛtʁ]; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Roman-Catholic priest, astronomer and professor of physics at the Catholic University of Leuven.[1] He proposed the theory of the expansion of the universe, widely misattributed to Edwin Hubble.[2][3] He was the first to derive what is now known as Hubble's law and made the first estimation of what is now called the Hubble constant, which he published in 1927, two years before Hubble's article.[4][5][6][7] Lemaître also proposed what became known as the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe, which he called his "hypothesis of the primeval atom" or the "Cosmic Egg".[8]

Tim, the "i don't come to conclusions" is a bad habit of some creatives, but eventually they do whether they intended to or not, so....

I don't disagree with rationalism and its place in architecture ... but where does that leave Ronchamp, Fallingwater, Brasillia? Is tim W a robot from the future? and is tim W also Non Sequitur?

Chris - Agreed. so... its minor in some ways but a better statement might be if you are mentoring,..." I or (we) are careful not to come to conclusions based on preconceived notions or established ways of doing things, and that is helpful in finding the best design to the needs of a project."

Ryan- Robot of the Future sounds kind or cool, scary. But I think you mean.... Is Tim W. outlining an example of what an architect of the future might look like, robotic in decision making or worse, an actual Robot"....Since I am not a robot from the future, nor do I make decisions in a 0/1 fashion. I know what you mean. I hope not. I don't think anything I have said will reduce the frequency of great buildings.

To your examples of great buildings. You know if you look at what the architects said about those buildings there were reasons they did what they did based on their past efforts, the clients, a desire to push what forms can do, and realities. When they made a series of conclusions and design decisions along the way they do show us those reasons in the forms and details. None of them to my knowledge stated they looked to meditation, a spiritual coming together or the confluence of unseen forces, intuition, or just faith in that process. You know they really wanted to point out the process are very grounded in nature like FLW so that their designs might be useful to others. Just make sure that you as the viewer today,...you do not project your feelings onto something that is just really well done...something that demonstrates it is well done. Be sure not to project fallacies onto buildings that are really well designed, blend with the site, address liturgical needs, have good visual balance, address human need, any number of admirable qualities by jumping to, "it can be achieved in a intuitive way by a tapping of spirit". I hope you know what I mean? Having said all that. I do think Artificial Intelligence will become a tool for architects and many many others in many human endeavors in the future. But it will be what we make it. It will be another tool. It does not follow that we will loose in the end, We may gain and loose, but hopefully all will work to better architecture. I feel hopeful and not so fearful.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.