The mark of a mature designer is the ability to take a blank sheet of paper and come up with creative, responsive ideas, efficiently and on a deadline: to be productively creative regardless of circumstance.

I can always tell the difference between designers who have really made the transition to being pros and those who are still trying to find their footing. It can be summed up in their attitude toward one thing: Inspiration.

If you're dependent on it, you're not a professional. If you can work without it, you are.

Look at the process of any well-established design architect and you will see that they have a system and a set of tools that they have developed to be efficiently and productively creative. These are habits of mind and tools which they know from experience can be used to generate and refine ideas, even if they're not in a creative mood.

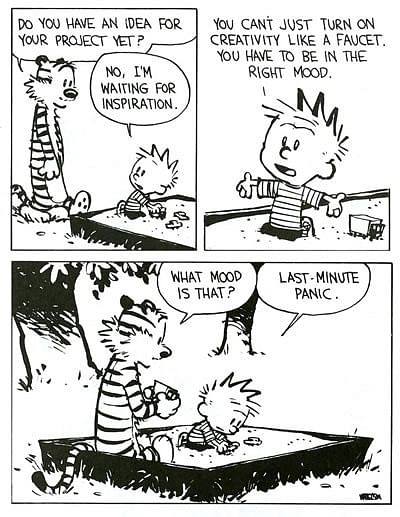

My intention here is not to denigrate inspiration as a source of greatness in design or anything else. When it strikes - Eureka! - inspiration can yield phenomenal results. But that's the problem: when it strikes. You can open yourself up to it, but you can't predict it or depend on it arriving on demand. If you can't find a way to be productively creative without it, you will forever be at the mercy of the muse, wasting time with a stuffed tiger in a sandbox. Clients and bosses tend to be rather unforgiving about that, so successful professionals learn to do without or find a less demanding career.

If you take a close look at what is taught in modern university architectural design curricula, what you will find is the presentation of a collection of accreted methods for productive creativity: tools for your toolkit. These are things that worked for somebody, somewhere, sometime to consistently facilitate creativity and generate results, sans la muse. Some of these things are good general-purpose methods, sketch-brainstorming or bubble diagramming for instance, while others are as idiosyncratic as Koolhaas' approach to observational criticism.

But "this worked for somebody once" isn't a very compelling academic sales pitch. At the very least, it admits that while we know it does work for somebody, we can't really say why it works with any confidence. To disguise this fact we get lots of peer-reviewed dross and jargon heaped on top of it to try and rationalize and sacralize it post hoc. Endowed professorships, highfalutin' criticism, and journal articles ensue. Lather, Rinse, Repeat.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that contemporary architectural theory is a solipsistic mess: mostly self-indulgent nonsense with pretensions to rigor.

This is not to say that theory can be safely dismissed in our search for creative productivity in practice. It is to underline its importance. A tool can be used much more powerfully when the user understands what it can do and how.

And what is the most important tool at the disposal of the professional designer? His own brain, of course. That's where a real, practical theory of design begins: at the contact patch between the possible and real, mediated by human thought.

Boundaries are where all the action is. I've spent my professional life inhabiting the crazy, convoluted boundary between theory and practice, process and product, concept and reality. In doing so, I've matured as a professional designer and come to understand a few things about how that works.

In what follows here, I will try to pass it on.

Practical theory and theory of practice in design.

1 Comment

Nice post. One reason seasoned professionals don't wait for inspiration is that having gone through their share of deadlines, one has to start drawing or lose a job. In doing so, they've found inspiration often times grows from tackling the problem at hand. Like of like impovising musically until a riff forms in your heat and you elaborate from there. The other indispensible item is studying precedents, of any historical period, history knowing no boundrys. When scratching around the problems edges, previous solutions will jump out of your head when they become relevant. Like opportunity, it favors the prepared mind.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.